American History for Truthdiggers: Nixon’s Dark Legacy

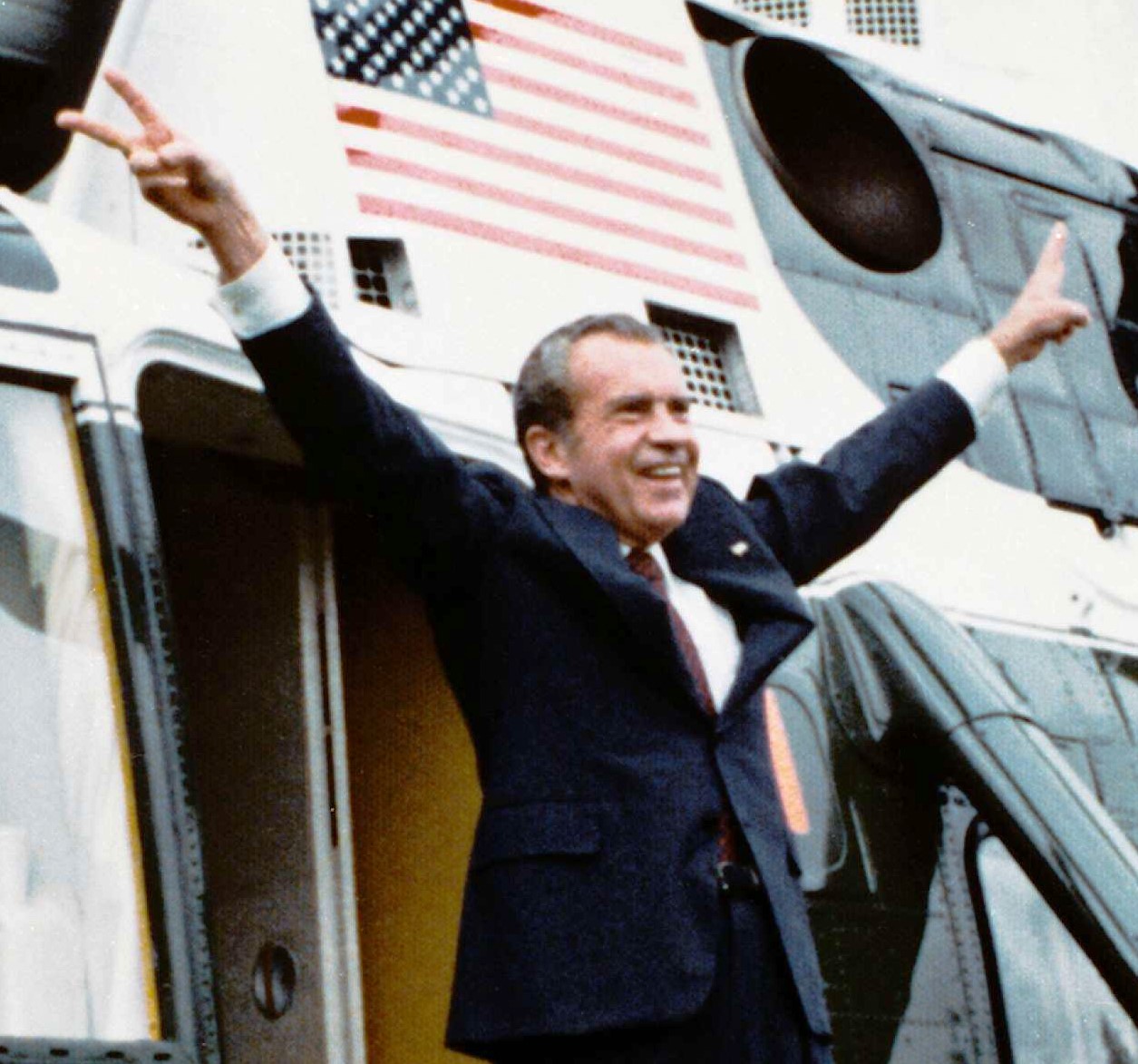

The president who arguably was the most corrupt in U.S. history lost the Watergate battle but won in his bid to lock U.S. politics on a rightward course. Richard Nixon leaving the White House by helicopter after resigning as president in August 1974.

Richard Nixon leaving the White House by helicopter after resigning as president in August 1974.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 31st installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, who retired recently as a major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 31 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23; Part 24; Part 25; Part 26; Part 27; Part 28; Part 29; Part 30.

He was corrupt. He was petty, angry and resentful. He was also one of the most astute politicians in the annals of the American presidency. Time after time he overcame obstacles and defeats to rise again. His genius, ultimately, was this: He envisioned a new coalition and knew how to channel white resentment over the civil rights and antiwar movements into political triumph. This was his gift, and his legacy. Americans today inhabit the partisan universe that Richard Milhous Nixon crafted. Republican leaders to this very day speak Nixon’s language and employ Nixon’s tactics of fear and anger to win massive white majorities in election upon election. Indeed, though Nixon eventually resigned in disgrace before he could be impeached, the last half-century has been rather kind to the Republican Party. Only three Democrats have been elected president in that period, and Republicans have reigned over the White House for a majority of the post-Nixon era.

For all that, Nixon remains an enigma. Though he crafted a lasting conservative majority among American voters, he also supported popular environmental and social welfare causes. He secretly bombed Laos and Cambodia and orchestrated a right-wing coup in Chile but also reached out to the Soviets and Chinese in a bold attempt to lessen Cold War tensions and achieve detente. A product of conflict, Nixon operated in the gray areas of life. Though the antiwar activists, establishment liberals and African-Americans generally hated him, Nixon won two presidential elections, cruising to victory for a second term. He was popular, far more so than many would like to admit. Although the 1960s began as a time of prosperity and hope, they produced a president who operated from and exploited anxiety and fear, and in doing so found millions of supporters. Nixon was representative of the dark side of American politics, and no one tapped into the darkness as deftly as he did. The key to his success was his ability to rally what he called the “silent majority” of frustrated Northern whites (most of whom traditionally were Democrats) and angry Southern whites (in what came to be known as his “Southern strategy”). It was cynical, and it worked.

White Backlash: Nixon’s Southern Strategy

Southern racists didn’t disappear in the wake of the civil rights movement; they simply rebranded as Republicans and expressed their intentions in less overtly racial language. Nixon, ever the consummate politician, knew this and set out to form a new American Republican majority, both for the campaign year of 1968 and for the future. The seeds of a new conservative ascendency had been in place for quite some time. In 1948, some Southern Democrats bolted the party and ran then-Gov. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for president as a “Dixiecrat,” on a ticket dubbed the States’ Rights Democratic Party. In 1964, many in the Deep South supported the Republican Barry Goldwater—this in a region so Democratic for so long that it was known in the party as the “solid South”—in his presidential bid against the incumbent, Lyndon B. Johnson. And, though it may be apocryphal, Johnson, a Texan, was reported to have said that his signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would “lose the South [for Democrats] for a generation.” Yet it was Nixon who effectively discerned these symptoms of Democratic weakness and crafted a conservative electoral coalition that has remained in place ever since.

During the 1968 presidential campaign, a young number-crunching political strategist, Kevin Phillips, explained a new Southern strategy to Nixon. The bottom line was that Nixon needed to win over Southern Democrats to the Republican side and to essentially give up any attempt to win the black vote. As a result, the Republicans would abandon civil rights indefinitely. Phillips told Nixon that the election would be won on “the law and order / Negro socio-economic revolution syndrome.” In other words, Nixon was being successfully urged to run on “law and order” in response to the massive urban riots that had so spooked Northern whites, and to say the same things that Southern Democrats had long been mouthing about race (although in less overtly racist language).

Nixon was from California and knew he didn’t have to speak as coarsely as Strom Thurmond. Instead, he used coded, but equally apocalyptic, language to win over fearful whites. “As we look at America, we see cities enveloped in smoke and flame,” he said in his 1968 acceptance speech at the GOP convention. Still, he declared, in the tumult there was the quiet “voice of the great majority of Americans, the forgotten Americans—the non-shouters; the non-demonstrators … they are not guilty of the crime that plagues the land.” What he meant, below the biblical eschatological imagery, was that he would be the candidate for a “silent majority” of whites—folks furious about inner-city riots, crime, hippies and a civil rights movement that most felt had gone too far, too fast.

In taking particular aim at the rioters, Nixon ignored official government reports that blamed the disorder on racism and entrenched poverty and he tied the maelstrom to a defiance of law and order. The year before his first term started, Nixon said the riots were “the most virulent symptoms to date of another, and in some ways graver, national disorder—the decline in respect for public authority and the rule of law in America. Far from being a great society, ours is becoming a lawless society.” The jab against Johnson’s Great Society, which in considerable part sought to help poor black populations in urban centers, was not lost on his enthusiastic listeners. Nixon had flipped the script, changed the paradigm. The real victims, the real minority, consisted not of blacks and other historically oppressed groups but working-class, white males! In a national address in 1969, Nixon plainly and forcefully unveiled his most famous phrase—“silent majority.” “… I would be untrue to my oath of office,” he declared, “if I allowed the policy of this Nation to be dictated by the minority who [oppose the Vietnam War] … and who try to impose [their views] on the Nation by mounting demonstrations in the street. … And so tonight—to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support.” Protest, in short, was no longer patriotic. Not in Nixon’s America.

Behind the national discourse and Nixon’s successful alignment of political sentiment was a staggering degree of cynicism. The president and company knew exactly what they were doing, exactly how they were manipulating white voters. Nixon adviser John Dean would later state that he “was cranking out that bullshit on Nixon’s crime policy before he was elected. And it was bullshit, too. We knew it.” More damning were the reflective comments of another key Nixon aide, John Ehrlichman:

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

It was vital, according to the Nixon team, to demonize black activists, especially advocates of black power. The chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, explained, “The whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to.“ Consider it racism-lite.

Still, it worked. The parties were sorted, once and for all, by race. In 1960, about 60 percent of blue-collar workers voted Democrat; in 1968, roughly 30 percent did. As for African-Americans, in 1960 more than 30 percent voted Republican; in 1972, just 10 percent did. Of course there were still far more whites than blacks in the United States, and Nixon played the numbers effectively. Haldeman saw the racial polarization and understood the numbers game sufficiently to advise Nixon: “must learn to understand the silent majority … don’t go for Jews and Blacks.” And a memo to Nixon from a member of his administration urged that he indirectly use this message in campaigning: “Today, racial minorities are saying that you can’t make it in America. What they mean is that they refuse to start at the bottom of the ladder the way you [the average middle-class American] did. They want to surpass you. … They want it handed to them.”

Turning this strategy into electoral sound bites required that Nixon make his point without mentioning race. He spoke directly to white resentment, but took it only so far. Many Nixonian Republicans ditched the Confederate battle flag and removed the N-word from their public vocabulary. Nixon would substitute crime, drugs and welfare for more overt racist tropes popular in the South.

Nixon’s pick for vice president, Spiro Agnew of Maryland, used coarser language and served as the attack dog of the 1968 campaign and the administration. He once had damned the “circuit-riding, Hanoi-visiting, caterwauling, riot-inciting, burn-America-down type of black leader.” Furthermore, throughout the campaign, Agnew used racial slurs such as “Polacks” and “fat Jap.”

There was more than just coded language and white resentment behind Nixon’s victories. Indeed, the Republicans spent twice as much as Democrats on radio and TV advertisement, demonstrating, even then, the power of money in politics. In 1968, Nixon won his first term by beating, barely, the Democratic candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. With former Gov. George Wallace of Alabama running an outwardly racist third-party campaign, 57 percent of American voters opted either for Wallace or Nixon. Only 42.7 percent went for the candidate of the once-ascendant Democrats. Indeed, Humphrey received a shockingly low 35 percent of the white vote in 1968, and Republicans would win a majority of whites in nearly every presidential election in the proceeding 50 years.

To win over whites, especially in the South, President Nixon had to placate the more overt racists in the country. He had his attorney general, John Mitchell, slow the pace of school desegregation, he refused to terminate federal funding for segregated schools, and he tapped a Southerner for the Supreme Court (his nomination of Clement Haynsworth of South Carolina was blocked in the Senate). Nixon would also rail against court-ordered desegregation measures such as forced-busing programs. It all worked like a charm. The “solid South” became the Republican South, and in 1972 Nixon would win a second term in a landslide. He was a vicious political infighter, as reflected by his characterization of his campaign battles and his administration’s tactics: “getting down to the nut cutting.” And indeed he would.

The Last Liberal or the First Conservative?

Nixon, especially when compared with later Republican presidents, was in many ways a moderate conservative. He was pragmatic, caring more about victory than ideology. He recognized the popularity of certain liberal government programs and went along with them. At least for a while. All this has led many historians to debate whether Nixon was the first conservative of a new era or the last liberal of a bygone, FDR-initiated era. There is some evidence on both sides of the scale, but, ultimately, Nixon was no liberal.

On the liberal side, Nixon would propose a guaranteed minimum income, the Family Assistance Plan, for all Americans as a substitute for welfare programs. No Republican after Nixon would dare to countenance such massive social spending. Then again, he knew it wouldn’t pass and used the plan as little more than a tactical move to protect his left flank, even advising Haldeman to “make a big play for the plan, but make sure it’s killed by Democrats.” And it was. Conservative Republicans loathed the proposed government spending, but the liberals felt the Nixon proposal was not generous enough. The measure was stillborn, just as Nixon had hoped.

Nixon would sign a fair amount of liberal legislation from 1969 to 1972, but it must be remembered that most of this was pragmatic, a nod to a still Democrat-dominated Congress. Nonetheless, some of Nixon’s achievements seem strange for a Republican president. In his first term, he extended the Voting Rights Act, funded the “war on cancer,” increased spending for the national endowments for the arts and humanities, and signed the Title IX measure, banning sex discrimination in all higher education that received federal funds. In his first term, federal spending per person in poverty rose by 50 percent and total government outlays for social protections more than doubled. His labor secretary, George Shultz, even established the “Philadelphia Plan,” which called for affirmative action hiring programs for construction union members employed on government contracts. At one point, Nixon called for a comprehensive national health insurance plan. Though he personally cared very little about the environment, he knew that most Americans did. Thus, he created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and sanctioned the first official “Earth Day.” Other environmental protections included the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Some of these measures so frustrated conservatives that Patrick Buchanan, one of the more ideological members of his team, warned Nixon that some within the party felt that conservatives were “the niggers of the Nixon administration.” On race, the Nixon administration was far from liberal, intervening to curtail desegregation measures in Southern school districts and successfully nominating two conservatives to replace liberal icons on the Supreme Court. The appointments of those judges would set the stage for the later dismantling of civil rights legislation. On busing, Nixon opposed court orders and, as previously mentioned, instructed his Department of Justice to slow the pace of integration. As he told Ehrlichman, “I want you personally to jump” on the DOJ “and tell them to knock off this crap. I hold them … accountable to keep their left-wingers in step with my express policy” of doing the minimum integration required by law. In 1972, Nixon called for a moratorium on busing measures and made his opposition to the court orders a touchstone of his re-election campaign that year.

Ultimately, Nixon’s occasional leftward moves were purely tactical. He hoped, eventually, to shift government in a more traditional conservative direction. He was only waiting for his moment. Nixon funneled much government spending to local control—so-called devolution—which allowed conservative areas to maintain covert racialized policies in spending. Nixon also railed against supposedly undeserving welfare recipients and reframed John F. Kennedy’s call to serve the country by urging Americans, in his second inaugural address, to ask “not just what will government do for me, but what can I do for myself?” It was the perfect mantra for a population that writer Tom Wolfe and others called the “Me Generation,” one that represented a shift from public service to private profit that would only strengthen with time. After his overwhelming electoral victory in 1972, Nixon began to move rightward. He proposed a budget that slashed government programs and called for the end to urban renewal projects, hospital construction grants and the Rural Electrification Administration. He cut spending on milk for schoolchildren, mental health facilities and education for students from poor families.

Nixon’s ultimate goal was to work the governmental system and then bring the liberal welfare state crashing down in due time. He sought to reorient American politics away from social spending and racially affirmative policies and toward more conservative government orthodoxy. He wouldn’t see his dream realized while he was president—mainly because he was forced to resign over the Watergate scandal—but his successors would achieve most of his goals. In that sense, he was, indeed, the “first” conservative, the vanguard of a new Republican ascendancy.

Unexpected Detente: Nixon and the World

Nixon’s practicality can best be seen in foreign policy, always his first love. Here Nixon was as savvy an actor as ever. What he had planned was a massive realignment of global affairs, an opening to a relationship with China and the Soviet Union, and some progress in lessening Cold War tensions. In his plans, Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser and eventual secretary of state, was a key player. Kissinger and other “realists” believed that pure national interests, not human rights or even political ideology, should drive U.S. behavior in foreign policy. This posture was framed as the “Nixon Doctrine,” the belief that the U.S. should first consider its own strategic interests and shape commitments accordingly. Gone would be the more moralistic instincts in foreign policy. The team of Nixon and Kissinger would personify the power of the “imperial presidency”—the centralization of foreign-policy power in the executive branch. Nixon would conduct most foreign affairs in secret, using back-channel communications and evading official channels in the State Department. He had, after all, little use for “elitist” experts.

Nixon’s first bold move was to reach an agreement with Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev to lessen tensions over Cuba. The U.S. would promise not to invade and the Soviets would cease building a submarine base and refrain from supplying Fidel Castro with offensive missiles. The problem was that this deal, like much else in his foreign policy, was reached in secret and thus had no legal standing. Nevertheless, it was a sign of limited rapprochement with the Soviets. Nixon also understood, correctly, that international communism was far from monolithic, and that the Soviets and the Chinese were increasing hostile toward each other. As such, Nixon famously decided to “go to China,” meet Mao Zedong and open a relationship between the two countries. Probably only Nixon could have pulled this off. A Democratic president would have been eviscerated from the right and condemned as soft on communism. Nixon, the longtime Cold Warrior, however, faced little opposition to his China policy. As he frankly told Chairman Mao, “Those on the right can do what those on the left only talk about.” Mao nodded and replied, “I like rightists!”

Months later in 1972, Nixon would head to Moscow and put the final touches on the first stage of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT). The treaty was largely symbolic and did not meaningfully reduce the stocks of nuclear weapons, but it was a start and another step in the direction of detente. Nonetheless, despite his limited successes, Nixon did little to change the long-term arc of Cold War tensions. After Nixon, less adept politicians, especially hawks in his own party, would dismantle detente and revitalize the arms race and tensions with Moscow.

One could argue, moreover, that Nixon and Kissinger were veritable war criminals. They secretly dropped a staggering number of bombs on Cambodia and Laos during the Vietnam War, killing tens of thousands and destabilizing both societies. Congress was not informed. Nixon also prolonged the war unnecessarily and increased the bombing of Hanoi. As a result, huge numbers needlessly died on all sides. Furthermore, the U.S. president and Kissinger supported a military coup in Chile to keep an elected socialist president from holding office. The resulting U.S.-backed government would torture its own people and “disappear”—secretly kill—tens of thousands of dissidents. The coup occurred on what many Latin Americans refer to as the “other 9/11”—Sept. 11, 1973. Finally, in Central Asia, Nixon supported Pakistan—in order to please its ally, China—in its brutal suppression of its Bengali separatists. Though the experts at the State Department warned him of what might happen, Nixon—true to form—conducted his policies in secret and backed Islamabad. It’s estimated that Pakistan, with America’s blessing, killed perhaps a million Bengalis in the ultimately unsuccessful war.

What, then, is the historian to make of Nixon’s foreign policy? Perhaps little except this: It was his and his alone. Nixon personally, along with Kissinger, did as he pleased. Sometimes, given Nixon’s astute understanding of foreign affairs, that meant dividing the two main communist global powers, China and Russia. Nixon’s foreign policy would also open up bilateral negotiations between the U.S. and the two other countries, contributing to a limited detente. It could also, however, be a brutal realpolitik—secretly bombing civilians, backing coups and suppressing foreign separatists. But nowhere was Nixon’s obsession with secrecy and victory at all costs more on display than at home, in what came to be known as the Watergate scandal.

The World of Watergate

“Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” —Richard Nixon in a 1977 interview

It began, one supposes, with the break-in and attempted wiretapping of the Democratic Party’s offices in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. But that wasn’t the half of it. Nixon may not have personally ordered the break-in or even known it was about to happen; the crime was in the cover-up, as it often is. Besides, the real story was this: From start to finish, the Nixon administration was one of the most corrupt, sneaky, vindictive and win-at-all-costs presidencies in history. Illegality was the hallmark of Nixon and his team. What would ultimately bring Nixon down was the existence of secret tape recordings of every conversation in the Oval Office, tapes that exposed the secrecy and corruption with which Nixon operated with his famously insular staff. The tapes revealed Nixon’s pettiness and bigotry. In one rather banal example, Nixon and Haldeman had the following conversation in 1971 about the TV host Dick Cavett:

Haldeman: We’ve got a running war going on with Cavett. Nixon: Is he just a left-winger? Is that the problem? Haldeman: Yeah. Nixon: Is he Jewish? Haldeman: I don’t know. He doesn’t look it.

The tapes revealed many such ugly conversations, but mainly depicted a man who was always at war with his enemies and saw himself as the perpetual embattled victim. Public enemy No. 1 was the Democrats. So it was that members of the Committee to Re-elect the President (aptly known by the acronym CREEP) would conduct a break-in at the Watergate Office Building. The problem was the burglars were caught and arrested. From there unfolded a cover-up of drastic proportions that would ultimately end the Nixon presidency.

Nevertheless, the Nixon team’s level of subterfuge, secrecy and illegality always transcended Watergate. For example, what Attorney General John Mitchell referred to as a program of “White House horrors” was expansive and prevalent both before and after the break-in. In 1971, when Nixon was told by Haldeman that the Brookings Institution think tank might have classified files on Vietnam that might embarrass the previous administration (of Democrat Lyndon Johnson) and the Democrats more broadly, Nixon ordered a break-in and theft, as documented later in the so-called Watergate tapes. “Goddamnit, get in there and get those files,” he ordered, “Blow the safe and get it!” In another incident, when Rand analyst Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, Nixon had his underlings break into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office in an attempt to find embarrassing files that could be used to blackmail him. The list goes on. Nixon discussed infiltrating antiwar groups with undercover agents and selling ambassadorships. CREEP would also harass and embarrass Nixon rivals by organizing fake rallies in the opponents’ names and thereby generating mountains of unpaid bills—an example of what CREEP member Donald Segretti called “ratfucking.” In addition, Nixon tried to plant a spy in the Secret Service detail of George McGovern, his 1972 Democratic opponent for the presidency, and ordered surveillance on Ted Kennedy to unearth dirt on the Massachusetts senator.

Nixon’s first vice president, Spiro Agnew, was indicted in Maryland for receiving bribes in return for political favors, and he resigned in October 1973, replaced by Gerald Ford. The corruption went further still. Attorney General Mitchell controlled a secret fund of over $150,000 to be used against the Democratic Party, specifically for forging letters, stealing campaign files and leaking fake news. Nixon also promised to offer executive clemency if the Watergate burglars were imprisoned, and Ehrlichman was ordered to pay them $450,000 in hush money. Nixon and Kissinger had the FBI tap telephones in order to gather intelligence on political enemies, placing illegal wiretaps on 13 government officials and at least four journalists. And this litany of malfeasance is far from comprehensive.

Just six days after the Watergate break-in went public, Nixon, in a conversation captured by his office taping system, discussed damage control and the cover-up with Haldeman. In 1973 and ’74, the entire edifice of corruption and cover-up came crashing down. Nixon was forced to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the Watergate affair, Archibald Cox. However, when Cox turned up the heat and began investigating Nixon and calling on him to turn over the Oval Office tapes, the president ordered the attorney general to fire him. When Elliot Richardson refused to do so, Nixon fired him; when Richardson’s deputy, William Ruckelshaus, also refused, Nixon fired him. The dismissals went down in U.S. history as the “Saturday night massacre.” Eventually the third in line, Robert Bork—whose nomination to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan would fail in the Senate years later—agreed to fire Cox. Still, Nixon’s efforts to block the release of the tapes failed. Both a congressional investigatory committee and the Supreme Court demanded the tapes be turned over. What these tapes revealed ruined Nixon.

The president’s advisers believed that Congress had the votes to impeach, convict and remove him, so Nixon resigned. Despite all the illegality, he would never stand trial or serve a day in prison. His successor, Vice President Gerald Ford, upon becoming president immediately pardoned Nixon and left in place all the structures, institutions and power bases that had allowed his perfidy to flourish. As such, nothing happened to stop future corruption in the Oval Office. Ford announced that “[o]ur Constitutional system worked,” but it was unclear that it had. Nixon almost surely would not have been caught if it wasn’t for the tapes and his blatant abuses. The Watergate committees narrowly focused their investigation on the break-in and cover-up, not paying attention to the broader corruption of Nixon’s administration or the imperial presidency that remained in place.

* * *

President Richard M. Nixon was a complicated man, a truly singular figure. He was defined by mistrust, opportunism and secrecy. Both at home and abroad he played the part of a master tactician, placing politics above principles at every turn. Although his backers found much to praise in his actions, more often than not he subverted democracy both at home and in other countries. Before Nixon and Watergate, most Americans trusted their federal government. That ended with Nixon’s resignation. As the extent of Nixon’s crimes and abuse gradually came to light, many Americans lost faith in the entire system. They blamed both sides—Democrat and Republican—ironically, and took to seeing all politicians as crooks. Thus, though Nixon never achieved the conservative dream of destroying Franklin Roosevelt’s social welfare state while president, he did unintentionally usher in the requisite rightward shift in American politics.

As the people lost faith in the ability of the federal government to do good, to improve life and accomplish great things, they ended up endorsing more conservative ideologies. Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, largely because of the Watergate scandal would be elected president slightly more than two years after Nixon’s resignation, but the humble Georgian would serve just a single, embattled term. Republicans, in fact, in the 28 years after Carter’s 1980 defeat, would own the presidency for all but eight years. This reorientation toward the right was, perhaps, the defining legacy of Nixon. He crafted a world of shadows, a more sinister view of government and the gradual empowerment of the executive branch that has by now seemingly resulted in a breakdown of the Founders’ hopes for separation of powers. There could have been no Reagan, or George W. Bush, without the example and accomplishments of a Nixon. There also couldn’t have been a Donald Trump, and that is something worth reflecting upon. Tricky Dick lost the battle—Watergate—but he may ultimately have won the war for America’s soul.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • James T. Patterson, “Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974” (1996). • Bruce Schulman, “The Seventies” (2001). • Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a retired U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.