American History for Truthdiggers: From Isolationism to a 2nd World Conflagration

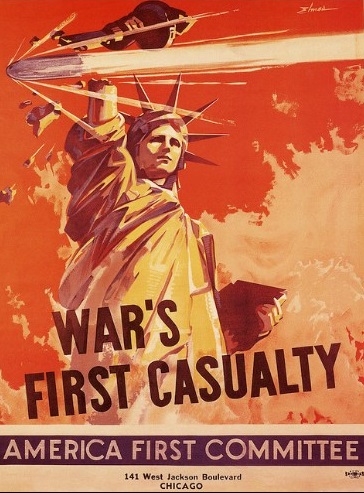

Global events and FDR whittled down 1930s opposition to intervention in Europe and steered the nation into World War II. The cover of a pamphlet of the America First Committee, the leading organization in opposing U.S. entry into World War II. The group's most prominent spokesman was the renowned aviator Charles Lindbergh.

The cover of a pamphlet of the America First Committee, the leading organization in opposing U.S. entry into World War II. The group's most prominent spokesman was the renowned aviator Charles Lindbergh.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 25th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 25 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23; Part 24.

* * *

Isolationism. Appeasement. Few words in American history have a more pejorative meaning than these. To this day, anti-war political figures are broadly described as naive isolationists ready to let the world burn in chaos; furthermore, current attempts at diplomatic compromise often are likened to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s perceived appeasement of Germany’s Adolf Hitler in 1938. At times such comparisons hold water. Usually they don’t. Each era and its prevailing context carry along contingent events and millions of decision makers with agency of their own. Rarely does one period bear any real resemblance to another. Few if any contemporary adversaries constitute the threat and pure evil of a Hitler. Fewer international compromises are as ill-fated as that made at Munich in 1938.

Still, we are told, the era between World War I and World War II continues to offer supposedly incontestable truths and lessons to be learned. In 1945 most Americans left the Second World War convinced—for the first time in our national history—that the U.S. must engage with and lead the world of nations. Furthermore, never again could a democratic nation compromise with or placate an authoritarian adversary. This, we are told, is the key lesson of the 20-odd years separating the two wars (1918-39). In certain instances, perhaps, the internationalists have been proved right. Then again, with the United States now engaged in countless wars and operating military bases around the globe, one must admit that the triumph of interventionism has had its cost, both to the budget and our republican ideals.

It must be said that there is some truth in the prevailing critique of the Western powers’ response to the rise of fascism in the 1920s and ’30s. Still, a closer look at the era and the United States’ unique role in it reveals the complexity and nuances of an international situation that was exceedingly difficult. The leaders of the 1930s did not have the benefit of the hindsight of today’s politicians, historians and critics. Almost none fully foresaw the horror of the coming war and Holocaust. To grasp the prevailing attitudes of the day, we must explore with open minds, and we must be willing to accept uncomfortable truths and at times quandaries.

Even after violence among European nations broke out in the late 1930s, most Americans remained highly skeptical of war and somewhat isolationist. Many prominent politicians, writers, artists and celebrities deeply feared a replay of World War I, a conflict they deemed to have been unnecessary if not outright criminal. Against this tide of isolationism, or, perhaps more accurately, anti-interventionism, stood a more internationalist collection of politicians and their sometimes wary champion, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Elected in 1932 to fix the Depression-era economy, FDR spent his first term focused on domestic issues. Nevertheless, he came from a globally inclined establishment family and had himself been a Wilsonian internationalist progressive and an assistant secretary of the Navy during the First World War. FDR saw the seriousness of the fascist threat before most Americans and spent much of his second term and the early part of his third term a few steps ahead of the people in his willingness to intervene against the Axis powers.

Still, being the canny politician he was, Roosevelt was very careful in leading the United States to war, moving in fits and starts toward joining the fight. In doing so, FDR severely stretched the limits of executive power and secrecy, demonstrating some of the dangerous tendencies he had indicated in his domestic response to the Great Depression. The result was not only a two-front war—which, admittedly, it was probably necessary to eventually fight—but a permanent alteration of the role and scope of federal power. No president since Roosevelt has actually declared war, but every president has unilaterally wielded the expanded executive powers that FDR unilaterally carved out for himself. This is how it happened.

Avoiding the Last War: World War I Memory and Isolationism

Americans and Europeans alike were traumatized by the First World War. The roughly 9 million combat deaths, the vast majority suffered by the European belligerents, surely was sufficient reason. Memories of what at the time was called the Great War were heavy on both sides of the Atlantic. Many political and cultural leaders vowed to never again support such a costly and ultimately fruitless nationalist bloodbath. Anti-war movements sprang up in the interwar years even before there was a looming new conflict to protest. The horror and absurdity of World War I nursed a fatalism in Europe, but American perceptions of that contest were more complex. After all, the U.S. military had been a latecomer to the war and suffered only a fraction of the casualties of the original belligerents. Still, Americans themselves were transfixed with the idea that the U.S. had won the war through its intervention. Some were proud of this, but many others were resentful: They felt the people of the United States had been deceived into becoming involved in an unnecessary war.

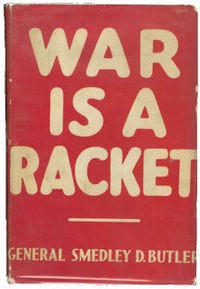

American opponents of WWI, who probably constituted a majority of the population in the 1930s, vowed to never again be “tricked” into intervening in a European war. They fell back on a long tradition of disengagement from foreign squabbles and looked inward. Only later would this popular and inherently American view be pejoratively dubbed “isolationist.” Martial spirits in general were losing their luster in the interwar period. Throughout 1935, retired Marine Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler, a two-time Medal of Honor recipient, traveled the country on a speaking tour for his book “War Is a Racket.” Butler was then the most decorated Marine in U.S. history, and his thunderous critiques carried the weight of his credentials. “War is a racket,” he declared, “It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.” Furthermore, he blamed past American interventionism on the influence of big business, exclaiming that he had “spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism.”

Butler’s earthy rhetoric resonated with an American public that was increasingly suspicious of the nation’s 1917 entry into World War I. Leading politicians, in fact, such as Sen. Gerald Nye, argued that the U.S. had fought in Europe only to secure the debts of Britain and to enrich the domestic arms industrialists—whom Nye called “merchants of death.” When Nye was head of the ultimately fruitless Senate Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry (1934-36) he publicly declared what many Americans had long thought: “When Americans went into the fray [WWI] they little thought they were there and fighting to save the skins of American bankers who had bet too boldly on the outcome of the war and had two billions of dollars of loans to the Allies in jeopardy.” Not coincidentally, Nye’s statement was uttered in the same year that Butler’s speaking tour was occurring.

Artists and writers, too, chimed in against future wars in Europe. The novelist John Dos Passos wrote, “Rejection of Europe is what America is all about.” Furthermore, Ernest Hemingway’s classic anti-war novel “A Farewell to Arms” (1929) was highly popular in the 1930s. Even revisionist academic historians penned influential books arguing that Americans had been duped into war by the British and their Wall Street financiers. So strong was the cultural and political anti-war sentiment that in the first postwar decade Americans rejected the League of Nations (proposed by President Woodrow Wilson), a security treaty with France, the World Court, free-trade policies and the forgiveness of Allied war loans. In the 1920s, in fact, Washington went so far as to negotiate sea-power reductions at the Washington Naval Conference (1921-22) and to technically make war illegal in the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928). Thus, when during the mid-1930s the rise of European fascism and Japanese imperialism became ever more threatening, most Americans—remembering with horror the Great War—had little stomach for a second world war.

By 1935, with Adolf Hitler already securely in power in Berlin, and with the Japanese fighting China over the province of Manchuria, many Americans were holding pre-emptive peace marches. In April, on the 18th anniversary of U.S. entry into the war, 50,000 veterans held a “march for peace” in Washington, D.C. Three days later, 175,000 college students nationwide held a one-hour “strike for peace” and demanded the abolition of on-campus ROTC programs. Responding to this popular outcry, the Congress would draft and President Roosevelt would sign the first of the so-called Neutrality Acts (there would eventually be five). This bill required the president to declare a total arms embargo on all belligerents, should any nations go to war, and to declare that all American citizens traveling on foreign ships did so at their own risk. The core of the legislation was a blatant attempt to avoid the last war’s perceived causes—Allied debts and deaths caused by submarines. Only 1939 wasn’t 1914, and the nature of the next war would be different, pulling in the United States once again despite its citizens’ best efforts.

As noted earlier, the United States was a latecomer to World War I, and the same was true for World War II. It took two years, three months and seven days from Hitler’s Sept. 1, 1939, invasion of Poland before America would unleash its full military might against the Axis powers—primarily Germany, Italy and Japan. Even then it would take a surprise attack by the Japanese to seal the deal. Indeed, it is rather remarkable that substantial portions of the American electorate and their representatives kept the nation out of both wars as long as they did. That delay was undoubtedly influenced by the tradition of American non-interference in Europe and the specter of the last war. However, bolstered with today’s knowledge of history, many commentators and historians of our own time lambaste the isolationist sentiments of 1930s Americans, even blaming them for the rise of fascist leaders and the ultimate horror of Nazi and Japanese policies. This may be unfair. Though, as we’ll see, the hesitancy of the Allies, and especially of the distant U.S., did embolden the fascist powers. Furthermore, given the challenge of the ongoing Great Depression, Allied powers often lacked both the capacity and will to meaningfully intervene before 1939.

Still, it must be said that the Allied—and American—response to fascist aggression in the 1930s was not the finest hour in the fight against that malignancy. When, in 1931, Japan executed a “false-flag” attack to justify a military invasion of Chinese Manchuria, much of the rest of the world made only a paltry protest. And when Benito Mussolini’s Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935 and the League of Nations (of which the U.S. was not a part) reacted by imposing an oil embargo, the U.S.—then producer of half the world’s oil—demurred. The U.S. decision and the collapse of the embargo defanged the concept of punishment: A cutoff of oil would have stopped Mussolini’s mechanized forces in their tracks. Ethiopia, despite putting up a gallant fight, soon fell to the Italians.

Next came a 1936 fascist coup in Spain, led by Gen. Francisco Franco, that set off a three-year civil war. When the duly elected leftist democratic government appealed to the Allies for help, it received none (except from the communist Soviet Union). The U.S. Congress, by a single vote, passed a new neutrality act that extended the arms embargo to both sides—the practical effect of which was to deny the Spanish liberals the means to fight. The fascist powers of Germany and Italy had no such qualms and sent arms, planes and eventually infantry to Franco. More than 2,000 Americans, usually idealistic leftists, defied U.S. government policy and enlisted to fight for the Spanish republicans. These American volunteers, who became known collectively as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, were thrown into battle with almost no training and often were used as shock troops; as a result they took heavy casualties. Such expatriate fighters were immortalized in Hemingway’s novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (1940). When Franco emerged victorious from the civil war, even President Roosevelt recognized the folly of the U.S. government’s decisions, conceding to his Cabinet that his Spanish policy had been “a grave mistake.”

At this point, America’s old allies began to feel they could no longer count on support from the New World. In early 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared that “he would be a rash man who based his calculations on help from that quarter … the isolationists are so strong & so vocal that [the U.S.] cannot be depended upon for help if [Britain] should get into trouble.” Thus when, later that year, Hitler demanded the cession of a German-speaking portion of Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland), Chamberlain and his French counterpart negotiated with the German leader in Munich without any meaningful backing from Washington. Not that the British were willing or able to make war in 1938. As Chamberlain himself stated, the Czech crisis was “a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom we know nothing.” Still, it must be said that previous U.S. inaction in Ethiopia and Spain discouraged British and French firmness at the Munich negotiations.

Indeed, Roosevelt appeared to be of two minds about the issues at stake. He feared Hitler’s expansive desires and, when the Allies ultimately handed over part of Czechoslovakia to the Germans, he privately noted that the British and French had left the Czechs to “paddle their own canoe” and predicted that these two allies of the U.S. would have to “wash the blood from their Judas Iscariot hands.” Even so, Roosevelt made clear to the British and French that they were on their own at Munich, declaring that the U.S. “has no political involvements in Europe and will assume no obligations in the conduct of the present negotiations.” Furthermore, when the unbacked Chamberlain did, in fact, hand over the disputed Sudetenland, Roosevelt was relieved and cabled Chamberlain the simple phase “Good Man.”

Soon after Munich, Hitler—who had actually desired war in 1938—swallowed up the rest of Czechoslovakia. In the years since the Munich debacle, it has been repeatedly argued that a firmer Allied stance might have staved off war or defeated an unprepared Hitler. Though not without merit, such moralistic proclamations belie certain facts. Hitler, seeking an immediate war with the European allies of the U.S., was disappointed when he felt obliged—under pressure by his own advisers—to compromise at the Munich Conference. What’s more, Britain and France were militarily unprepared and their allied dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) had made clear they were unwilling to fight for the Czechs. And, given that the Allies could not depend on an even less prepared and inclined United States, they had little choice but to compromise. Truth be told, they probably succeeded in buying themselves a year to prepare for war.

Munich, and Germany’s subsequent seizure of Czechoslovakia, did, however, change everyone’s calculus. Hitler would be sure to get his war next time, and Britain and France vowed to fight for the likely next target of the Nazis—Poland. It was also a watershed for FDR, if not for all Americans. Roosevelt concluded that Hitler was a “mad man” and “a nut,” and the president shifted his own (often secretive) policy to “unneutral rearmament” and tacit support for the Allies. Unfortunately, someone else, too, learned a lesson from Allied weakness at Munich—Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Certain he could not count on the Allies to check Hitler, Stalin began considering a deal with his fascist archenemy, Hitler. Just before the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Soviets would sign a nonaggression pact with Germany, and the two autocracies secretly agreed to divide Eastern Europe between themselves. Still, both Stalin and Hitler were aware that this was but a marriage of convenience that would last only until the great ideological war between fascism and communism would begin.

Further proof of American hesitancy could be found in its perfidious response to the Jewish refugee crisis of the 1930s and ’40s. When Germany occupied Austria in 1938 without a shot fired, 3,000 Jews per day applied for visas to the U.S. in the capital city of Vienna. Unfortunately, due to the harsh restrictions on Jews and East Europeans entering the U.S. under the 1924 National Origins Act, the U.S. consulates in Germany and Austria could legally process only 850 visas per month. Eventually, the consulates had a backlog of some 110,000 visa applications. By 1938, of course, it was no secret that the Nazis were persecuting Jews across the Third Reich, stripping them of citizenship and civil rights and even subjecting them to violence. Still, America proved to be little help to hundreds of thousands trying to escape. In a bit of Kafkaesque political tragedy, under German law Jews who left the country could take only a very small amount of money with them. The immigration-restrictive U.S. forbade granting visas to people “likely to become a public charge”—meaning poor people. Thus, with unemployment raging in Depression-era America, there was little hope this ban would be lifted or that a sizable number of Jews could thread the legal loophole and seek refuge in the “Land of the Free.”

It’s not that the Germans wouldn’t let Jews go at that point in time. In fact, Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels announced that “if there is any country that believes it has not enough Jews, I shall gladly turn over to it all our Jews.” Furthermore, a Nazi newspaper commented, “We are saying openly that we do not want the Jews while the democracies keep on claiming that they are willing to receive them—and then leave the guests out in the cold.” And indeed the U.S., and the other democracies, largely did. A Fortune magazine survey in 1938 indicated that only 5 percent of American respondents were willing to raise immigration quotas for Jews. Even Roosevelt, who would later push the nation toward war with Germany, parroted the popular American line. Asked by a reporter, just five days after the worst Nazi pogrom against Jews to date, whether he would “recommend relaxation of our immigrations restriction,” he answered simply: “That is not in our contemplation. We have the quota system.” It was not his or the nation’s proudest moment.

All in all, the U.S. alone cannot bear the blame for Hitler’s rise or the eventual Holocaust. However, due to a range of factors described, America and its erstwhile allies failed to demonstrate the will or capacity to check the rising fascist states. It would take outright war for the British and French, and the machinations of a rather secretive and increasingly internationalist American president, to halt Nazi and later Japanese aggression.

Getting the War He Wanted: Roosevelt and Executive Power (1935-41)

Though he so often, and for so long, bent to the political whims of an isolationist public, it now seems clear that from early in his presidency FDR saw the fascist threat and slowly worked to pull the U.S. toward a de facto—and eventually official—state of war. When, in 1935, the U.S. Congress rejected joining the World Court, both Hitler and Mussolini had already risen to power. Roosevelt, surmising that these fascist states may one day have to be checked, lamented to a friend that “we [in the U.S.] face a largely misinformed public opinion.” Roosevelt had once been a supporter of President Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations (1920-1946) and was even inclined to partner with the league to punish Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, but he also knew he was far ahead of isolationist public opinion on such matters.

Domestic politics was always on the president’s mind. During the Ethiopia invasion, FDR told Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley that “I am walking a tightrope. I realize the seriousness of this from an international as well as domestic point of view.” He feared that if he got too far out in front of Congress at that moment he would hand the isolationists a weapon to use against him in the upcoming presidential election campaign.

Even after his 1936 re-election, when Roosevelt gave a modest speech in Chicago in October 1937 about the threat of fascist aggression in Europe, he took half measures. Despite strongly illustrating the threat from the new authoritarian regimes, he backtracked with reporters just one day later, declaring sanctions “out of the window” and claiming the U.S. was “looking for a program … [that] might be called stronger neutrality.” After the Chicago speech failed to rally the American people, Roosevelt allegedly stated, “It’s a terrible thing, to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead—and to find no one there.”

By the late 1930s—after the fall of Ethiopia, Manchuria and Spain and the start of German rearmament—the president had privately made it clear to European democratic leaders that he was “with them,” but he felt the need to be less candid at home. Though he regularly expressed his dismay with many of the more restrictive parts of the five Neutrality Acts, he felt obliged to proceed slowly with any military preparations or diplomatic promises. This, of course, was problematic. Roosevelt’s private assurances to France and Britain had little effect on Hitler’s policies, since, as historian Donald Watt astutely concluded, “deterrence and secrecy are largely incompatible notions.”

Matters came to a head on Sept. 1, 1939, when Hitler unleashed a swift, brutal invasion of Poland. The British and French quickly declared war on Germany but could do little to save the doomed Poles. FDR stayed neutral, of course, but took a view different from the one President Wilson had taken in 1914. Roosevelt admitted his own inclinations when he announced to Americans that he “cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought.” Still, pro-Allied rhetoric was one thing, but tangible support was another matter. Though FDR now knew he needed to try to repeal the Neutrality Acts, he was obliged by law to invoke the acts on Sept. 5. This mandated an embargo on all arms to belligerents on both sides—including Britain and France. British officials told the American ambassador to London that they were “depressed beyond words” that the U.S. had invoked the neutrality law. Roosevelt began work to weaken the legislation but had to tread carefully, writing that “I am almost literally walking on eggs” in dealing with Congress and public isolationist sentiment.

By November 1939, FDR convinced Congress to repeal certain aspects of the Neutrality Acts, but the legislature still insisted that all transfer of materials to the Allies be on a cash-and-carry basis and that absolutely no credits be granted to Britain or France. After Hitler took western Poland and began shifting divisions to the French border, Roosevelt confided his deep concern to the journalist William Allen White. “What worries me,” the president stated, “is that public opinion over here is patting itself on the back every morning and thanking God for the Atlantic Ocean (and the Pacific).” Declaring that technology made the oceans a less secure barrier than in the past, Roosevelt expressed his quandary and his proposed way forward, writing, “Therefore … my problem is to get the American people to think of conceivable consequences without scaring the American people into thinking they are going to be dragged into this war.” FDR truly was walking a tightrope. At the very least, he knew by late 1939 that Hitler must be defeated and that U.S. support for the Allies would be essential to that end, and he may even have realized American entry into the war would eventually be necessary. Still, he couldn’t admit all this publicly.

When, after a brief lull dubbed the “Phony War” in Europe, Hitler struck westward in May 1940 and shattered the British and French defenders in just six weeks, matters became ever more urgent for Roosevelt. France would soon surrender, while the British army barely escaped the beaches of Dunkirk in France. The British, though relieved by the alterations to the Neutrality Acts, still resented American caution and paucity of support. America’s Anglo friends feared that the U.S. would resist war almost to the last Briton and then intervene only at the final moment; as such, a frequently heard complaint among British officials was “God protect us from a German victory and an American peace.” Still, the fall of France had changed the war’s calculus and convinced Roosevelt that Britain must endure. He would spend the next 18 months redoubling efforts, legal and otherwise, to provide Britain’s new prime minister, Winston Churchill, with everything he needed to keep his country afloat. It was the beginning of a robust and historic relationship.

Churchill had an American mother and personified Anglo-American unity. Furthermore, he knew the limitations of British arms and realized his nation’s destiny lay with the U.S.—with American support and, eventually, American intervention. He would work hard to cultivate the strongest of relationships with FDR via letter, telegraph and telephone. Roosevelt, for his part, decided privately that the new national emergency required continuity of executive leadership. Justifying his decision as a matter of duty rather than ambition, Roosevelt permitted his political allies to arrange a “spontaneous” demonstration in favor of nominating him for an unprecedented third term as president. Simultaneously, FDR took unprecedented steps to win public support for the Allies, using the FBI to monitor “subversive” groups through illegal wiretaps and to secure information about isolationist groups and leaders. Still, while working behind the scenes to move the nation closer to war, Roosevelt regularly proclaimed, disingenuously, on the campaign trail that “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again. Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” In just over a year, millions of Americans would be sent to fight in Europe and the Pacific. In November 1940 Roosevelt won another convincing political victory and a third term.

The first order of business was to send to Britain 50 World War I-era destroyers that Churchill had requested. Sensing he would lack the necessary support in Congress, Roosevelt slyly—some have argued illegally—proceeded by executive order. First, he had the nation’s top military leaders declare the ships obsolete, then unilaterally used his powers as commander in chief to dispatch the destroyers across the Atlantic. The next issue was finance. In December 1940, with the Nazi air force bombing London, Britain’s ambassador carried a message to the U.S. that came straight from Churchill. “Britain’s broke. It’s your money we want,” he stated, adding that “the moment approaches when we shall no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and other supplies.” Knowing the U.S. would be in dire straits if Britain were to fold, Roosevelt enunciated a new doctrine that would bear his name. In a stark speech he portrayed a world divided between good and evil and spoke of “an emergency as serious as war itself,” calling on the U.S. to become “the great arsenal of democracy.”

To do so meant further alteration of the Neutrality Acts and a new “lend-lease” bill to overcome the cash-and-carry provisions still on the books in Congress. The theory was that the U.S. would provide arms and vehicles to the British—and, after Hitler’s eastward invasion, the Russians too—under the ludicrous pretense that the supplies would be returned after the war. Some sarcastically asked, “How does one return used bullets?” At the time, FDR’s earthy analogy was that of lending a neighbor your hose to put out a fire in his house. Clearly lend-lease constituted far more than that. This time Roosevelt knew he had to go through Congress, and though his isolationist opposition mounted one last fervent counterattack, the president got his bill passed by a largely partisan majority. On one point the isolationists were right: Lend-lease was a major step toward war and it shed any lingering pretense of U.S. neutrality.

The anti-interventionists were essentially correct in their prediction that arms shipments to the Allies would lead to American entry into the war. Even before lend-lease, Roosevelt was taking a number of secretive steps to coordinate with the British. He had already authorized a top-secret joint planning exercise between American and British military leaders to coordinate strategy in a future wartime alliance. Other executive orders—without congressional sanction—extended the U.S. naval defense perimeter eastward and authorized naval vessels to “patrol” the area. FDR then sent soldiers and Marines to occupy Greenland and Iceland to deny these islands to the Nazis. By June 1941, the U.S. defense perimeter extended deep into the North Atlantic. Exactly what the isolationists had feared—a clash between German submarines and American shipping—now seemed inevitable, just as it had in 1917.

Roosevelt worked hard to sell his interventionist and increasingly bellicose policies to a still somewhat skeptical public. In one radio “fireside chat,” the president even divulged the supposed existence of a Nazi map (later proved to be bogus) showing a plan by Hitler to seize Latin America. That he needed to so motivate the public remained obvious when, later in 1941, the extension of the first peacetime draft in American history passed Congress by only one vote.

Churchill may have declared, in the wake of lend-lease, “Give us the tools, and we will finish the job,” but in reality the prime minister always expected an (eventual) outright U.S. intervention in the war. Furthermore, though the lend-lease bill passed Congress, it included a restrictive clause that “[n]othing in this Act shall be construed to permit … the convoying of vessels by naval vessels of the United States.” In other words, no armed escorts, no potential for armed naval conflict in the North Atlantic. Astonishingly, just as Roosevelt was publicly denying even considering naval escorts, he secretly advised the military that “the Navy should be prepared to convoy shipping in the Atlantic to England.” By mid-1941, despite the president’s initial proclamations to the contrary, the U.S. Navy would engage in an undeclared shooting war with German subs. FDR would argue that tactical necessity demanded this course of action. After all, the Nazis were sinking British ships five times faster than the vessels could be replaced. Germany seemed capable of starving the Brits of supplies and thereby winning the war.

Nevertheless, what transpired in the North Atlantic was remarkable and more than a little disturbing. Without congressional authorization, Roosevelt had armed naval vessels track German subs and call in their positions to British ships and aircraft; eventually the U.S. vessels were ordered to “shoot on sight.” By year’s end, American sailors were killing and dying in a naval shooting war. One proof of Roosevelt’s clandestine—if not illegal—intentions was his advice to the British not to announce the change of U.S. naval policy in favor of convoys. He told Churchill that “it is important for domestic political reasons … that this action be taken by us unilaterally. … I believe it advisable that when this new policy is adopted here no statement be issued on your end.” Though some knowledge of the undeclared naval war would eventually come to public attention—especially after the U.S. Navy suffered casualties—it is notable that just two men, Churchill and Roosevelt, were coordinating an extralegal war on the high seas without U.S. congressional authorization. Without a doubt, future American presidents would claim equal right to unilaterally deploy U.S. military personnel, though that eventuality could not yet be foreseen.

In one last classified mission (kept secret even from the first lady), Roosevelt and Churchill met secretly on twin warships in Placentia Bay off the coast of Newfoundland. For three days, these two unofficial allies hashed out future wartime coordination and even the contours of a postwar world. The resulting document, known as the Atlantic Charter, assumed victory in a war the U.S. had not even entered. The executive presumptuousness of both the meeting and the document was truly unprecedented in the annals of American foreign policy. By the fall of 1941, the United States—at least its naval arm—was at war in the Atlantic. On Sept. 11, FDR publicly declared, “From now on, if German or Italian vessels of war enter our waters … they do so at their own peril.” It was obvious to any serious observer that the U.S. and Germany would soon be fully at war. However, to the surprise of many Americans, the impetus for formal declarations would occur on the other side of the world, at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Plunging Toward War: The View From Japan (1921-41)

At the end of 1941, the U.S. and Japan—two nations that did not want war, at least with one another—would lock in monumental conflict. Japan had been a major regional power for nearly a century, having rapidly industrialized in the late 19th century and decisively beaten the Russians in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, the first time ever that a Western great power had been defeated by an Asian enemy. However, despite Japan’s naval and battlefield victories, the United States—with President Theodore Roosevelt as lead negotiator—had mediated a peace that denied the Japanese most of their land conquests in Northeast Asia. Then, even after Japan allied with Britain in World War I, none of the major participants at the Versailles Peace Conference, including U.S. President Wilson, would acquiesce to a racial equality clause in the treaty. The final straw of racial frustration came with the United States’ 1924 National Origins Act, which cut off all immigration from Japan and denied a path to citizenship for many Japanese-Americans. As a proud nation, with a powerful military machine, and recently victorious in two consecutive wars, Japan resented the second-class status relegated to it by haughty European imperialists. Many Japanese military men felt that these colonial Western nations had set the rules of the game, long benefited from them, and then changed the rules when the newly resurgent Japanese sought to play.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, increasingly militarized Japanese regimes sought to right perceived past wrongs and carve out an “Asia for the Asians,” which meant, in practice, Asia for the Japanese. The primary target was China. After Japan seized Manchuria in 1931, few Western countries expressed more than passing concern. Thus emboldened, the Japanese army next invaded China proper in 1937 and seized much of that country’s eastern coast. The Japanese were themselves prejudiced against their fellow Asians and fought a war of terror in China, executing perhaps 300,000 civilians in the infamous “Rape of Nanking.” Despite moral blandishments from Washington—and with Europe fully focused on Hitler’s Germany—Roosevelt didn’t even invoke the Neutrality Acts. Realizing that the cash-and-carry provisions in the legislation would benefit the Japanese over the cash-poor and disorganized Chinese, FDR avoided that through the strained justification that (at that point) neither side in the Japanese-Chinese conflict had formally declared war. Though the U.S. was unlikely to sell arms to the Japanese aggressors (at least overtly), invoking the cash-and-carry provisions of the latest Neutrality Act would have opened that possibility.

Japanese military aggression relied on a vibrant trade with the United States throughout the late 1930s. Even after a Japanese warplane sank the USS Panay in broad daylight on the Yangtze River, killing two American sailors and wounding dozens (for which Tokyo did apologize and pay reparations), Roosevelt did not cut off trade. Ironically, due to a dearth of natural resources, the Japanese war machine could run only with ample supplies of American scrap iron and petroleum. In August 1937, at a time when the U.S. was continuing to provide vital war materials to the Japanese, The Washington Post ran the headline “American Scrap Iron Plays Grim Role in Far Eastern War.”

It was clear by 1940 that Japan was bogged down in an indefinite land war in China and that, despite its early successes, victory remained a distant prospect. Furthermore, in order to perpetuate the war, Japan was highly dependent on certain foreign raw materials, especially oil, 80 percent of which it received from the U.S. This situation seemed to grant extraordinary leverage—in the form of sanctions—to Washington, but it was a dangerous game to play with a desperate adversary. As early as the autumn of 1939, U.S. Ambassador Joseph Grew warned the president that “[i]f we cut off Japanese supplies of oil … [Japan] will in all probability send her fleets down to take the Dutch East Indies,” a regional rich in rubber and petroleum. Secretary of State Cordell Hull agreed with the warning against provoking Japan, arguing that the U.S. had already secretly committed to Britain that if America went to war, Washington would pursue a “Germany First” strategy. Hull, and senior military leaders, thus argued that armed confrontation with Japan would “be the wrong war, with the wrong enemy, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.”

Indeed, the U.S. was only beginning its own rearmament and had neither the capacity nor the strategic desire for a two-front war. The plan, in the increasingly likely case of war, was to destroy Hitler’s forces and then, if necessary, confront Imperial Japan. But it was not to be. The U.S. had long been a Pacific power, especially after the 1898 seizure of the Philippine Islands, which U.S. military planners now considered indefensible. Despite that assessment about the Philippines, U.S. concern about Japanese aggression was great enough to prompt Washington to try sanctions against Tokyo. The result was predictable: Both sides sped toward war through misunderstandings, misreading each others’ intentions, and inaccurately assessing ability to pressure the other party.

In the fall of 1940, after Japan occupied northern French Indochina, the hawks in FDR’s Cabinet—Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau and War Secretary Henry Stimson—argued that full-fledged sanctions would force Japan to curtail its aggression. Over the next 12 months, the U.S. would ratchet up sanctions (which have a poor historical track record), first on aviation gasoline, then on scrap iron and, finally, on oil and most other commodities. Despite dozens of diplomatic engagements between the Japanese ambassador and top U.S. officials, the embargo on oil, especially, placed the two countries on a collision course.

Tokyo and Washington were now running on different clocks. The U.S. hoped to stave off war with Japan while checking its adversary’s most blatant aggression. The Japanese, on the other hand, had only an 18-month oil reserve and calculated, based on U.S. rearmament schedules, that it would have only two years’ worth of naval superiority in the Pacific. As such, Tokyo had determined—unless Washington lifted the sanctions—to go for broke and pursue a two-pronged attack, on resource-rich Southeast Asia (including the Philippines) and on the main U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. The plan was ambitious and ill-advised, but not insane. The Japanese hoped to shock the U.S. into early negotiations by sinking much of America’s Pacific Navy, an act that would buy Tokyo the time and resources to bring the China war to a successful conclusion. Even the most bellicose Japanese planners realized that an all-out, protracted war with America would lead to strategic defeat. Still, Japan’s leaders felt cornered and desperate. And so they risked it all.

By late November, FDR and his Cabinet knew that war with Japan, though undesired, was likely. Secretary Stimson wrote in his diary that Roosevelt said at a meeting that Japan was likely to soon launch an attack against the U.S. without warning. “The question,” Stimson recounted, “was how we should maneuver [Japan] into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.” American code breakers had some forewarning that a Japanese attack was likely but knew neither the time nor location of the strike. Such statements, information and newly unclassified documents have created a veritable industry of conspiracy-theory peddlers who—much like the 9/11 “truthers”—claim that Roosevelt had prior knowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack and allowed more than 2,000 sailors to die so he could finally bring his unwilling nation into war.

No smoking gun has been, or is likely to be, found. It stretches the imagination to think a sitting U.S. president would allow thousands of sailors and five of the nation’s battleships to be lost when a much less costly provocation for war would have done just fine. The conspiracy theorists also ignore the skill of an enemy that executed a well-planned assault. These charges also turn a blind eye to numerous American intelligence failures that led to the disaster. The main American failure, though, was what historian George Herring has called a “failure of imagination.” U.S. planners knew an attack was imminent but assumed it would fall in Southeast Asia and in the Philippines (where one eventually would) and underestimated the capacity of the Japanese military to deliver such an audacious blow to Hawaii. At a fundamental level, the most likely explanation for the onset of World War II is this: Having learned in 1938 the dangers of appeasement, the U.S. spurned cautious expediency and backed a proud Japanese nation into what Tokyo saw as a choice between war or surrender. Japan chose war, and the rest was history.

* * *

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese forces surprised the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor. In a stunning attack, they sank ships and caused numerous casualties. Four days later, Hitler’s Germany declared war on the United States. War had finally come to America. Given the machinations of FDR and his internationalist allies, and the perceived provocations against Imperial Japan, perhaps Pearl Harbor shouldn’t have been so much of a surprise. Nonetheless, nothing would ever be the same. The United States would mobilize its extensive military might and help win a war across two oceans, becoming, after victory in this “good war,” both an Atlantic and a Pacific superpower. It remains to be seen whether this, ultimately, was a net positive for the American republic.

Unfortunately, lost in the triumphalism of world war victory was much memory of the process of U.S. entry into this war. It is, after all, astonishing, given the almost unanimous internationalism of the postwar era, to recall just how reticent about intervention most Americans remained as late as 1941. Also lost is a fair, and perhaps critical, accounting of FDR’s secretive and unilateral actions in the years before America’s entry. Furthermore, since the reputed “lessons” of the interwar era have led to a seemingly limitless expansion of U.S. military might around the globe, perhaps there is now no better time to contemplate the devious means by which this now canonized president led a great nation to war.

Roosevelt’s road to war cleared the way for an unprecedented expansion of the powers of the presidency. His dubious, often illegal, executive measures formed the basis for an increasingly imperial presidency and today’s national security state. Nazi Germany, almost all would now agree, had to be stopped. So, perhaps, did Imperial Japan. The cost, though, to the American republic would prove to be grave indeed. Even “good wars,” after all, have consequences.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001). • George Herring, “From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776” (2008). • Ira Katznelson, “Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time” (2013). • David M. Kennedy, “Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1946” (1999). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.