American History for Truthdiggers: Reconstruction, a Failed Experiment

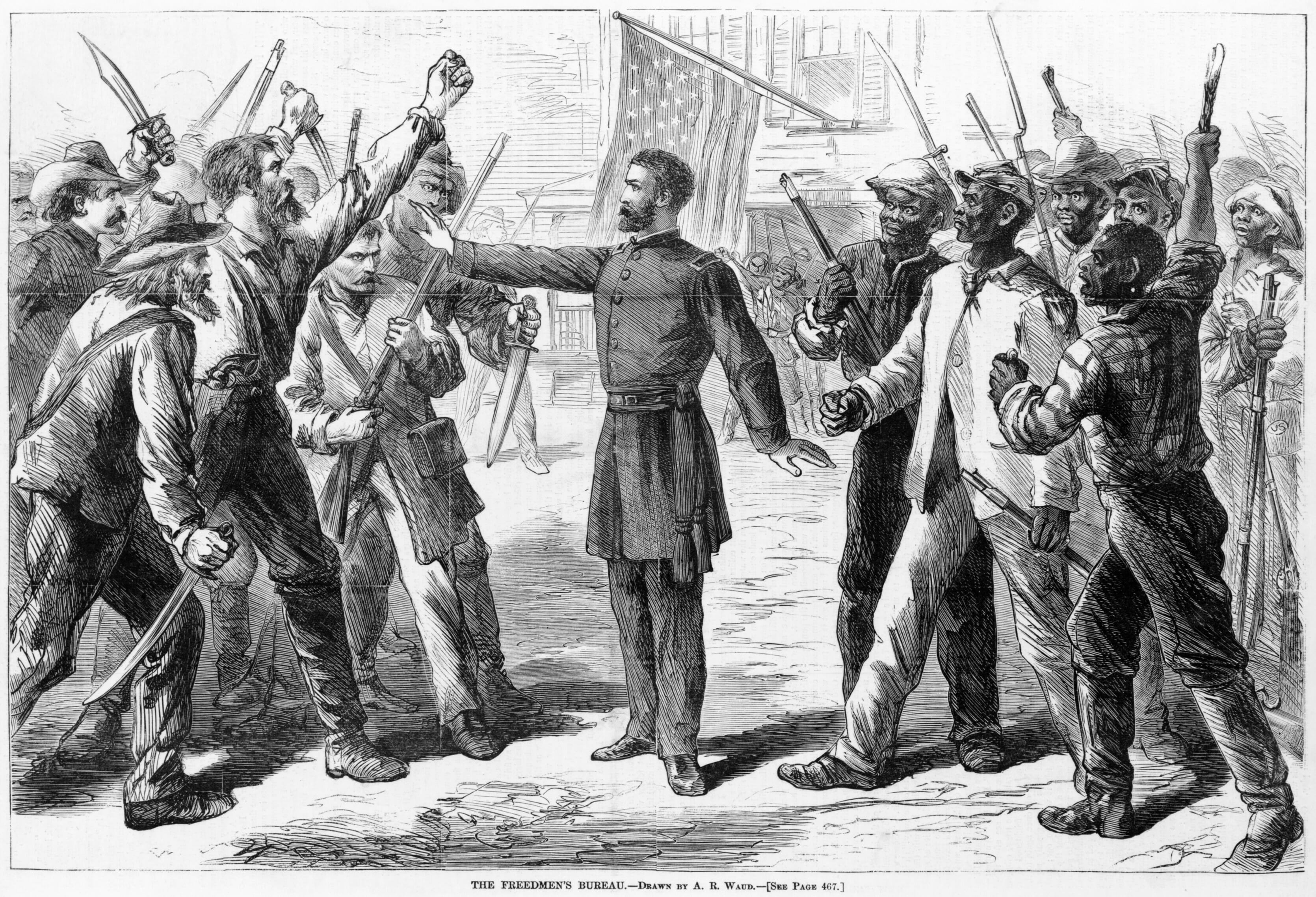

After many thousands of Northerners died in a war aimed in part at freeing the slaves, white America lacked the will to follow through. A Union officer, representing the new Federal Freedmen’s Bureau, mediates an encounter between Southern whites and former slaves. The illustration, published by Harper's Week in 1868, is by A.R. Ward.

A Union officer, representing the new Federal Freedmen’s Bureau, mediates an encounter between Southern whites and former slaves. The illustration, published by Harper's Week in 1868, is by A.R. Ward.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 18th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 18 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17.

* * *

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over—… Or does it explode? —Langston Hughes (1951)

It was, perhaps, the greatest betrayal, the ultimate lost opportunity, in all of American history. The failure of Reconstruction (1865-77)—the reunion and reorganization undertaken after the Civil War—was a dark, yet briefly vibrant, moment in our collective past. This was a time of promises made but not kept, mainly promises to the newly freed slaves. The results of this lost opportunity for genuine civil rights and racial equality resonate in the present day.

Most Americans know something about our great civil war. Lay enthusiasts, historical re-enactors and even otherwise disengaged citizens can recount the basic contours of great battles, horrific casualties and the sudden freedom granted the slaves. Well, it makes sense: War, when it is not actually unfolding around you, is exciting. Conversely, the process of picking up the pieces, rebuilding a nation and creating new social structures for a forever changed country, the stuff of Reconstruction, is far less well known.

It should be otherwise. The dozen or so years after the American Civil War (1861-65) are among the most consequential in our history and have far more relevance to contemporary affairs than almost any other era. Nearly every issue Americans grapple with today—citizenship, race, terrorism, affirmative action, the scope of federal power, and reparations payments—all have strong roots in the period of Reconstruction. It was in these years that the U.S. government would briefly triumph and ultimately fail in a grand experiment to achieve the twin goals of postwar Reconstruction: justice and reconciliation.

The historiography (the history of historians) of Reconstruction has a long, sordid history. Readers of a certain age, in fact, may recognize some of the older interpretations of this period. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, historians such as William A. Dunning and his many students at Columbia University—the so-called Dunning school of scholars—dominated this field. According to this highly biased, Southern-influenced interpretation, the problem with Reconstruction was that it went too far. The story went something like this: President Abraham Lincoln had a plan for leniency toward the former Confederates, and his successor, Andrew Johnson, attempted to follow the Lincoln vision. He was thwarted, however, by Radical Republicans in Congress who pushed too far too fast and were overly punitive with the former rebels. They sent “carpetbaggers” (outsiders) from the North who worked with “scalawags” (or collaborators) to force racial equality and Northern capitalist dominance on the poverty-stricken South. In this view, former slaves simply weren’t ready for the vote and other civil rights, and the Reconstruction-era governments in the South were massive, corrupt failures. Luckily, by 1877, a compromise was reached, the federal troops left, and heroic former Confederates in the newly formed Ku Klux Klan drove out the Yankee carpetbaggers and restored “home rule” to their governments.

If that interpretation seems shocking by modern standards, well, it should. What’s most disturbing is that some version of the Dunning interpretation remained mainstream (and in students’ textbooks) well into the 1950s; until, that is, the civil rights era. That this vision prevailed so long reflects a culture of white supremacy that existed long after the Civil War and, some argue, still exists today. The whole edifice was premised on the notion that blacks, as former slaves, were incapable of self-government and required the steady, paternalist hand of their white Southern superiors. After the civil rights era (1954-68), a new generation of historians took a fresh look at Reconstruction and rehabilitated the efforts of Radical Republicans, lauding their ultimately unsuccessful attempt to guarantee basic civil rights to newly freed blacks.

What, then, can now be said about Reconstruction? Perhaps this: It was a remarkably idealistic attempt to bring freedom and equality to 4 million souls only recently held in bondage. Some of the brief achievements of this period (such as blacks voting, holding office and serving in Congress) would not again occur on a broad scale for a century. The failure of these attempts was not due to corruption or the unpreparedness of blacks; rather, the racism and apathy of white Americans—both south and north of the Mason-Dixon Line—doomed black Americans to generations of slavery by another name: Jim Crow.

An Enormous Challenge: Reconstruction Begins

“If war among the whites brought peace and liberty to blacks, what will peace among the whites bring?” —Frederick Douglass (1875)

Americans began arguing about how best to reconstruct the Union before even winning the war. In fact, various generals and politicians experimented with several methods of reunion and racial reconciliation. Some Union generals treated escaped slaves like lowly laborers, either paying low wages for hard jobs or returning them to the plantations they had fled. This approach was common in the occupied Mississippi Valley and parts of Louisiana during the war. On the Carolina coast, however, the planters fled the approaching Union forces during the war and left behind some 10,000 slaves. Union generals granted land to the slaves and created a remarkable, if brief, experiment in black self-rule. White New Englanders flocked to the Carolina Sea Islands to teach blacks to read, treat them medically and train them in farming techniques. In another remarkable turn, Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ own plantation, Davis Bend, in Mississippi was seized and turned into a “negro paradise,” as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant declared it should be. The plantations were settled and worked by the slaves as a collective, and Davis Bend proved remarkably profitable for the rest of the war.

Such experiments, however, dealt only with the relatively few slaves left behind in the face of Union armies. After the South’s surrender, the U.S. government confronted a much larger challenge: What to do with some 4 million former slaves made free by the war? The size of the task was staggering. Six percent of all Northern white males had died as a result of the conflict, along with 18 percent of Confederate men. The freeing of the slaves was, by some counts, the largest confiscation of wealth (and “property”) in world history. The South was in ruins—it needed to be rebuilt and its surrendered rebels somehow reintegrated into the Union. It would have been a daunting task even if everything had gone right.

Besides, the South may have been beaten on the battlefield, but it was less clear that Southerners considered themselves truly defeated. Union Gen. James S. Brisbin wrote to a congressman in December 1865, “These people are not loyal; they are only conquered. I tell you there is not as much loyalty in the South today as there was the day Lee surrendered to Grant. The moment they lost their cause in the field they set about to gain by politics what they had failed to obtain by force of arms.” The average Confederate soldier may well have turned over his rifle (though often the soldiers kept their firearms) and taken off the uniform, and he may even have accepted the freeing of the slaves; however, he fully expected to maintain the edifice of white supremacy and return to the ways of the antebellum South.

The Worst President in History? Andrew Johnson and the Failure of Presidential Reconstruction

Johnson lacked all the qualities that made Lincoln a great president. He was combative, had no charisma, failed to compromise and was wickedly racist. When Johnson showed up drunk and gave a rambling, inebriated inaugural address, he was acting completely in character. Johnson was from Tennessee but had remained loyal to the Union, the only Southern senator to do so. He hated the planter aristocracy and the secessionists, but he was even less tolerant of blacks he considered uppity and Northern abolitionists. Johnson planned Reconstruction on his own terms. He lavished pardons on any Confederate official who wrote to him or visited Washington, and insisted that the leadership of the Southern states remain in place and that these states should quickly re-enter the Union. He had no love for famed abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, of whom he said at the conclusion of a meeting: “He’s just like any nigger, and he would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”

Few Confederates, even high-ranking ones, were severely punished. There were no war crimes trials, military tribunals for treason, or mass hangings. Even Confederate President Jefferson Davis spent but two years in prison. The Confederacy’s vice president, Alexander Stephens, would even rejoin the U.S. Congress within a decade of the war’s end, and end his career as governor of Georgia. As soon as white Southerners were back in charge of local government, the Deep South states quickly enacted “black codes,” or laws, controlling every aspect of the freedmen’s public lives. As an example, the Louisiana Black Codes read, in part:

Section 1. … [N]o negro or freedman shall be allowed to come within the city limits … without special permission.

Section 2. … [E]very negro freedman who shall be found on the streets after 10 o’clock without a writ-ten pass … shall be imprisoned and compelled to work five days on the streets.

Section 5. No public meetings … of negroes shall be allowed. …

Section 7. [N]o freedman who is not in the military service shall be allowed to carry firearms. …

Indeed, the Southern states, with the planter class back in charge, had largely negated the North’s achievements of the war and crafted a new version of slavery. All-white police forces and judiciaries, often composed of Confederate veterans still wearing their gray uniforms, enforced the black codes. Union veterans and Radical (meaning more liberal) Republicans in Congress began to wonder, if there was to be no punishment for the Confederates or meaningful freedom for the slaves, what the war had even been for.

The Radical Moment: Congressional Reconstruction

Johnson and his Southern compatriots would later argue that “radical” Reconstruction was despotic and unnecessary. Nevertheless, the record demonstrates the opposite. Through presidential vetoes and white Southern intransigence, the South brought radical Reconstruction upon itself. When Congress passed the remarkable Civil Rights Act of 1866, Johnson quickly vetoed it. This legislation provided for equality before the law (but not the vote) for the freedmen. Congress overrode his veto with a two-thirds majority—the first time a major bill was passed over a presidential veto in U.S. history. To solidify black rights, the Congress even passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which stated:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

And, taking matters a step further, the Republican Congress also passed the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed the vote to black men (but not women). In a remarkable turn of events, black men had gained civil and political rights in just three years and over the objections of the president. The Republican Party—which hadn’t existed in the South before the war—began winning elections and even placing blacks (often former slaves) in elected offices. Eight hundred black men would serve in state legislatures from 1868 through 1877; a black man was briefly governor of Louisiana; more than a dozen blacks served in the U.S. House, and one in the Senate. White Southerners called this “Negro Rule,” but in reality it was the first ever attempt at democracy in the South. After all, in a few Deep South states, former slaves constituted an actual majority of the population.

Johnson was appalled by both the 14th and 15th amendments and the radical changes unfolding in Southern society. And by suddenly removing the Radical Republican Edwin Stanton from his position as secretary of war, he violated the recently passed Tenure of Office Act (which required congressional approval of such moves). That was the last straw for an already frustrated Congress. The House voted to impeach President Johnson, and the Senate came within one vote of the two-thirds majority required to remove him from office. Even though he remained president, Johnson had been politically castrated and wouldn’t run for re-election in 1868. He would be succeeded by the great Union war hero Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Grant’s Democratic opponents, Horatio Seymour and Francis P. Blair, would play the race card—actually, the racist card—in their failed 1868 campaign. Blair claimed that the Republicans had placed the South under the rule of “a semi-barbarous race of blacks who are worshippers of fetishes and polygamists” and who long to “subject the white women to their unbridled lust.”

Though blacks had won remarkable political power in a few short years, they generally lacked any true economic clout. There were early efforts, though, spearheaded by the likes of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to offer 40 acres and in some cases supposedly a mule to freedmen along the Southeast coast. In January 1865, before the war had ended, Sherman enacted Special Field Order 15 from Savannah, Ga., thereby setting aside such confiscated land for thousands of freedmen. Unfortunately, by September 1865, after the war’s end, President Johnson rescinded Sherman’s order and mandated the land be restored to the Confederate owners. Some Union generals publicly opposed the president’s decision. Gen. O.O. Howard—head of the new Federal Freedmen’s Bureau, designed to support the newly emancipated slaves—was nearly fired and court-martialed after writing to his superiors: “The lands which have been taken possession were solemnly pledged to the freedman. Thousands of them are already located on tracts of forty acres each. The love of the soil and desire to own farms [is] the dearest hope of their lives.”

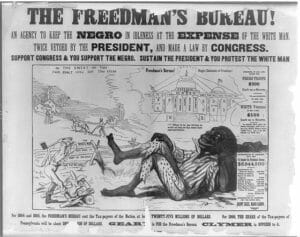

Howard’s Freedmen’s Bureau was itself a remarkable institution. Though always small (never having more than 900 employees in the entire South), the bureau worked toward the education and betterment of the former slaves in what was the earliest known federal welfare program of any size. Still, opposition cartoons in the South depicted the bureau—which was remarkably successful in most cases—as a haven for freeloaders and lazy black men. (This language rings as remarkably similar to 20th-century complaints against modern welfare programs.)

Some Radical Republicans—to their immense credit, given the times—wanted to go a step further. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, unsuccessful fought for the confiscation of 400 million acres of Confederate land and its redistribution to the freedmen. Stevens, in opposition to Johnson’s view, believed the federal government ought to treat the Southerners as a “conquered people” and reform “the foundation of their institutions, both political, municipal and social,” so that “all our blood and treasure [were not] spent in vain.” Given the century of Jim Crow laws, lynching and political disenfranchisement that followed Reconstruction, it appears that men like Stevens were ultimately right and exceptionally ahead of their times. Such a redistribution of land would be radical even today and carry the tainted labels of “socialism,” “affirmative action” and “reparations.” Still, in hindsight, the denial of land ownership to most freedmen doomed them to labor in the fields and on the plantations of the onetime slaveholders. The terms of work and the social caste system remained remarkably consistent with the pre-war “Old” South.

Domestic Terror: The KKK Counterrevolution

It was a time of great terror. Though pitched battles between armies became a thing of the past, the South was far from pacified and remained an extraordinarily violent place. The federal Army—which after the war never counted more than 30,000 men across the entire South—did what it could to stanch the violence and protect victims, who were almost always former slaves. The most infamous group of revisionist former rebels was known as the Ku Klux Klan, or the KKK for short.

The members of the Ku Klux Klan, formed in Pulaski, Tenn., by Confederate veterans, wore white sheets over their heads in order to appear “as the ghosts of the Confederate dead.” In reality, of course, the Klan was merely a resurrection of the old militias and slave patrols that had enforced white supremacy for centuries. Its tactic was violence; its goal, counterrevolution; its method, terrorism. The Klan was extraordinarily violent, probably killing more innocent black men, women and children during Reconstruction than the number of Americans killed in the 9/11 attacks of 2001. After all, in Texas alone, in just 1865-1868, over 1,000 blacks were murdered by whites.

Other statistics and events are equally shocking. In October 1870, bands of whites in South Carolina’s Piedmont region drove 150 freedmen from their homes and committed 13 murders. In Louisiana in 1873 a legally organized and accredited black militia tried to defend the parish courthouse in Colfax against a superior white force of former Confederates armed with rifles and a small cannon. The black militia held out for a time but was ultimately overwhelmed. At least 50 were summarily executed under a white flag of truce.

Furthermore, after Northern troops pulled out of the South and turned government over to white locals, the reign of terror continued. Some 3,000 blacks were lynched between 1882 and 1930.

Among the reasons given for these murders: “[a black man] didn’t remove his hat”; an African-American “wouldn’t call [a white man] master.” In yet another case, a white killer simply had “wanted to thin out the niggers a little.”

It’s not as though the Klan could not be controlled, even though it would be fair to characterize the U.S. Army campaign of 1866-77 as a form of what we would now call counterinsurgency. In fact, whenever the Army had the will, leadership and capacity to suppress the Klan, it did so. After the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 was passed at the request of President Grant, the law proved remarkably successful in stymying the power of the KKK throughout much of the South; for the first time ever, a certain class of crimes was brought under federal jurisdiction. Ultimately, it was a question of will, not ability. The simple fact was that Northerners had little stomach for more fighting and complained of the expense—in blood and treasure—of continued occupation. In the end, the Northern public lacked the will necessary to win the peace as it had won the war.

The Lost Cause: Southern ‘Redemption’

“There was a right side and a wrong side in the late war, which no sentiment ought to cause us to forget. … [The South] has suffered to be sure, but she has been the author of her own suffering.” —Frederick Douglass (remarks at Madison Square in New York City, Decoration Day of 1878)

The former Confederates never really accepted defeat or the reorganization of their social system. In reality, they bided their time, waged secret violence and, perhaps most importantly, crafted an alternative “Lost Cause” narrative. According to this (remarkably resilient) yarn, the South had actually outfought the North and was beaten only because it was overwhelmed by Northern superiority in numbers and resources. The South hadn’t really fought for slavery, but rather for states’ rights and Southern honor. In reality, soldiers on both sides—blue and gray—had more in common than they realized when they were killing each other in massive numbers. According to the Lost Cause myth—which still exists—“reconciliation” between the sections was more important than “justice” for blacks or “punishment” for rebels.

Southern generals were rarely punished and rose to prominence rather quickly as Reconstruction wound down in the 1870s. They gave popular speeches, both in the North and South, speaking of the need for “reconciliation” and “reunion,” words that tended to serve as code for abandonment of the former slaves to the will of their old masters. In 1877, in Brooklyn, N.Y., former Confederate Gen. Roger Pryor told a crowd that applauded him:

The Union is re-established … over the hearts of people. … But slavery was not the cause of secession. For the cause you must look … to that irrepressible conflict between the principles of state sovereignty and federal supremacy. … Impartial history will record that slavery fell not by effort of man’s will, but by an act of Almighty God, and so, fellow citizens, the soldiers of the late war are brought today to fraternize over the graves of their departed comrades, and renew their vows of fealty to the Constitution.

Such sentiments were remarkably common and accepted on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. As violence, and the slow removal of federal troops from the South, began to keep blacks from the polls, Southern Democrats began winning statewide elections. By 1875, former Confederate Gen. James L. Kemper, who had been in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, was governor of Virginia and gave a speech to unveil a statue of Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson in Richmond. On the occasion, Gov. Kemper revealed not only a new heroic statue but his own version of the rhetoric of Lost Cause and reconciliation. He exclaimed:

Not for the Southern people only, but for every citizen of whatever section … this tribute … is to be cherished, with national pride. … Stonewall Jackson’s career of unconscious heroism will go down as an inspiration. … It speaks with equal voice to every portion of the reunited common country … to inspire our children with patriotic fervor. … Let Virginia demand and resume [its] ancient place in the sisterhood of States. …

Considering that “Stonewall” was a traitor who resigned his U.S. Army commission to fight for a treasonous Southern slaveholding secessionist republic just 14 years earlier, this was remarkable rhetoric. That it resonated among some Northerners as well as Southerners is more peculiar. But so it was.

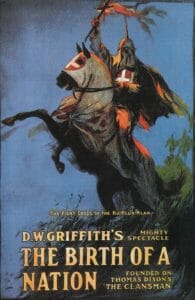

The Lost Cause myth took on a life of its own and, eventually, drafted a Reconstruction chapter as well. According to this version, it was actually the KKK that was heroic during Reconstruction, protecting rightfully white leadership and the honor of Southern white women. As late as the early 20th century, this was somehow a mainstream interpretation. It was in 1915 that D.W. Griffith’s incredibly successful silent film “The Birth of a Nation” depicted the Klan as the heroic savior of the white South from venal Northern carpetbaggers and insufferable, lustful black savages. How mainstream was the film? Well, it was a favorite of President Woodrow Wilson (a Virginian) and received a private screening at the White House.

The South may have lost the war, but it most certainly won the peace.

Betrayal: The Retreat From Reconstruction

“The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” —W.E.B. Du Bois (1913)

The abandonment of Southern blacks shouldn’t have come as a surprise. After all, what did it truly mean to remake the South in the North’s image when the North itself was so virulently racist in the mid-19th century? Most Northerners had signed up for the Army to save the Union and cared little for the slaves. Soon after the war, The Cincinnati Enquirer announced, “Slavery is dead, the negro is not, there is the misfortune.”

Most Northerners were tired of Reconstruction by the mid-1870s. The commitment of troops and money to protect what many saw as corrupt and inefficient “black” administrations just didn’t seem worth it. Besides, the economic mismanagement—the Panic of 1873 was the worst financial disaster in 40 years—and staggering corruption that plagued the Grant administration only further alienated the Northern populace from what seemed a distant and futile task down South. The tragedy of it all, of course, is that when the U.S. government stuck with it, used the Army and enforced the law, the Reconstruction governments achieved remarkable successes—political wins for blacks that most Southern states wouldn’t see again until the 1980s! Unfortunately, most of the white North was fickle and bigoted.

Besides, even if the Republican president and Congress stood by the goals of Reconstruction, the Southern-dominated Supreme Court soon eviscerated much of the congressional legislation protecting black civil rights. Indeed, it would take a century for the courts to begin appropriately applying the 14th and 15th amendments to Southern blacks. In 1883, the court would rule that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional. And, after all, it was the Supreme Court of the United States that would later, in 1896, rule in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation was legal!

A lackluster candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, ran on the Republican ticket for president in 1876. The party was seen as tainted by corruption in the Grant administration and mismanagement of the economy and had lost control of the Congress two years earlier, in 1874. It was almost amazing that the little-known Hayes, a former governor of Ohio, managed to keep the vote close in what turned out to be a disputed election with many abnormalities. It was unclear who had won a few Southern states. It appeared, however, that Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic nominee, had the majority of both the popular and electoral vote. It was at this moment that the Republican Party—for which Reconstruction and justice had become a political liability—struck a nefarious deal.

For the sake of party and power, “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes, as he was subsequently called, sold out the millions of Southern blacks who had loyally supported the Republicans for years. The candidate who had lost the popular vote would become president in exchange for his promise to remove the U.S. Army from the South. And so he did. Ironically, he also turned the South over to Democratic one-party rule for a century to come. Hayes was obviously lacking as a political tactician. The truth is, however, that by the time of the 1876 election the majority of Northern whites had tired of Reconstruction. More concerned with economic depression than black civil rights, Northerners were ready to throw in the towel and turn the South back over to its traditional white leaders, come what may. The Compromise of 1877 only reinforced what was by then inevitable: the abandonment of the South’s blacks. Looking back, a dozen years after Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, one could plausibly wonder: What had all those men died for in the Civil War?

* * *

Justice and reconciliation. These were, ultimately, the twin goals of postwar Reconstruction. A century and a half on, though, the keen observer wonders if the two goals were ever compatible. To seek justice and equality for the freedmen seemed to inevitably make reconciliation with white former Confederates ever less likely. To prioritize reconciliation with the former rebels seemed to sentence black people to a prolonged bondage of sorts, under the segregationist regime of Jim Crow.

Still, this author sees Reconstruction as an admirable attempt—however far ahead of its time it might have proved to be—at true social and political equality in the United States. It is remarkable that Reconstruction was even attempted in America of the 1860s and ’70s. If only the U.S. Army had stayed longer, enforced the law more stringently, redistributed land and wealth more equitably; if, in other words, the nation had stuck with the Radical Republican approach. Perhaps, then, the civil rights movement of the 1960s could have begun a century earlier, thousands of lynchings been avoided, and the riots, violence and racial upheaval of our own day dodged.

Seen in that albeit provocative light, the real hero of Reconstruction was the congressional “radical” Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, the man who called for free land and civil equity for Southern blacks, at the point of the bayonet if necessary. He would die before Reconstruction truly got underway, and upon his death in August 1866 Stevens, a white man, for the last time challenged his countrymen to “rise above their prejudices.” As he wished, he was buried in an integrated cemetery, an action taken, in the words of his self-composed epitaph, “to illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life: Equality of Man before his Creator.”

Alas, there would be no such equality in the lives of his countrymen. The American experiment was, at it always seems to be, a step behind its egalitarian rhetoric. The United States, it turns out, was not ready for true Reconstruction—and more’s the pity. Many thousands of Northerners died during the American Civil War, and it would have been highly satisfying to imagine they had died for something more than a century of Jim Crow and slavery by another name. But that is the real America, warts and all. And that, in the end, was the failed experiment in Reconstruction.

Still, Reconstruction achieved much and demonstrated what was possible if, someday, Americans had the moral and political will to see it through. The brief Republican governments of the South brought the region its first-ever public school system. It brought more hospitals, more asylums for orphans and the insane. South Carolina in this period would fund medical care for the poor. Alabama would provide free legal counsel for indigent defendants. These were social gains the South wouldn’t see again in most cases until the 1970s or even in some cases until today.

We still live with Reconstruction’s incomplete mission, with its failed promises. Reconstruction remains; its weight presses upon a divided American body politic, sundered yet by class, race and gender. We are reconstructing still, and remain fixed in the midst of our unfinished revolution.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • David W. Blight, “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory” (2001). • James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 17: “Reconstructing the Union, 1865-1877” (2011). • Eric Foner, “A Short History of Reconstruction” (1990). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • Richard White, “The Republic for Which it Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896” (2017).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.