AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty

Dig

AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty

Dig

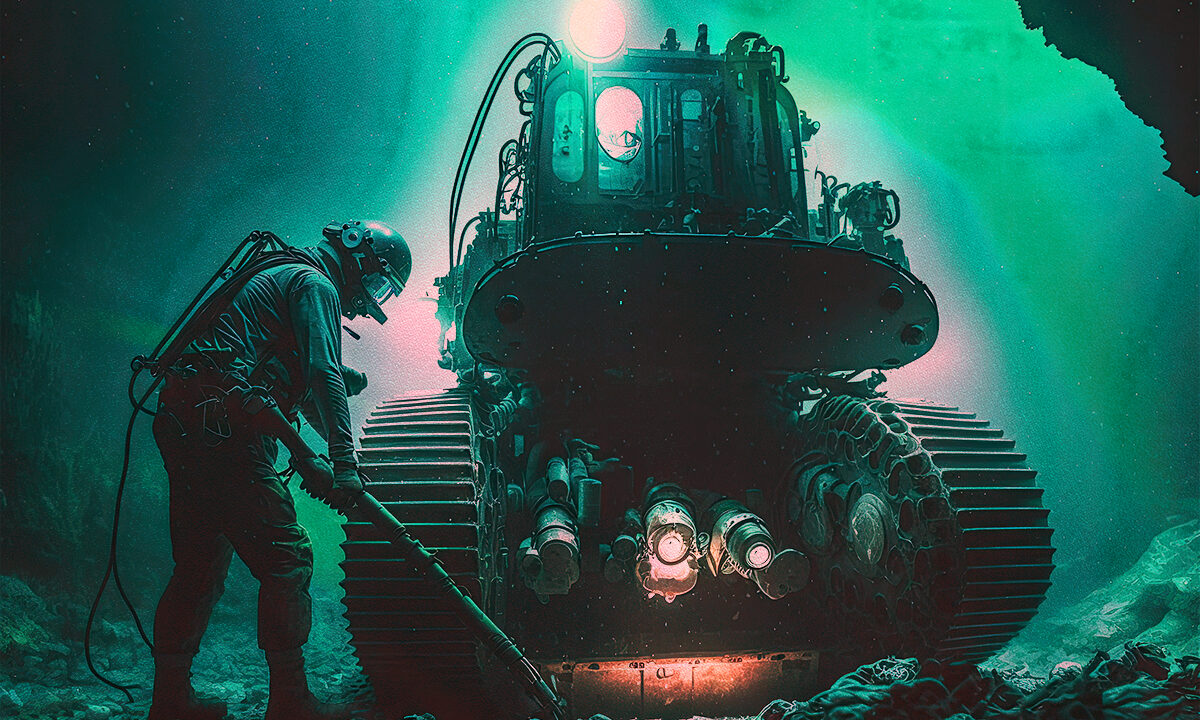

The Scramble for Deep-Sea Minerals

This Dig series explores the development and impact of a quickening international competition to plumb the ocean's deepest reaches for the minerals required for renewable-energy technologies, from wind turbines to EV batteries. A Dig curated by Rachel ReevesThe Existential Dilemma of Offshore Riches

The Cook Islands and other Pacific island nations are considering opening their oceans to mining. Is it worth the risk to their way of life?

On an overcast morning in March, a few dozen residents of the Cook Islands gathered to welcome visitors to the Port of Avatiu on the northern coast of Rarotonga, the country’s most developed island, with a traditional Māori ceremony. Beside a two-ton mining ship, chiefs cracked coconuts with bush knives and lit a small fire on the dock’s concrete. As drummers beat rhythms into hollowed-out logs and a man dressed in tī leaves sang chants of welcome in Cook Islands Māori, the captain and crew of the specially refitted vessel, the Anuanua Moana, proceeded down the gangway and onto the dock. Women garlanded them with vines harvested on long hikes over jagged coral. In a few weeks, the Anuanua Moana would set off on a research expedition, pursuing minerals used in electric vehicle batteries and other technologies widely viewed as essential to the transition away from fossil fuels. Never before have the minerals been brought up from miles deep.

Dignitaries observed the formalities from beneath a pop-up tent. Among them was Prime Minister Mark Brown. “It’s a really important day,” he said. He described the Anuanua Moana as a symbol of “the future prosperity of our country” and noted proudly it is “rare for an exploration vessel of this kind to be based in the South Pacific, let alone in the Cook Islands.” Indeed, the ship had traveled from Galveston, Texas, to a tiny country 2,000 miles east of New Zealand that is home to fewer than 15,000 residents, a journey of some 5,500 miles. In a country where the speed limit is 25 miles per hour and pretty much everyone has a relative in common, the Anuanua Moana quickly became the talk of the town. Dig deeper Jul 31, 2023Should We Be Mining the Ocean Floor?

The race is on to regulate an international competition for minerals in the world's least explored and most mysterious ecosystems.

Miles beneath the surface of the ocean, about as deep as Mount Kilimanjaro is tall, things look a little peculiar. It’s a world freezing and dark, where the pressure is high enough to crack steel. The few humans who have visited those depths describe the environment as otherworldly.

Dig deeper Dig Discussion