American History for Truthdiggers: Washington’s Turbulent Administration (1789-1796)

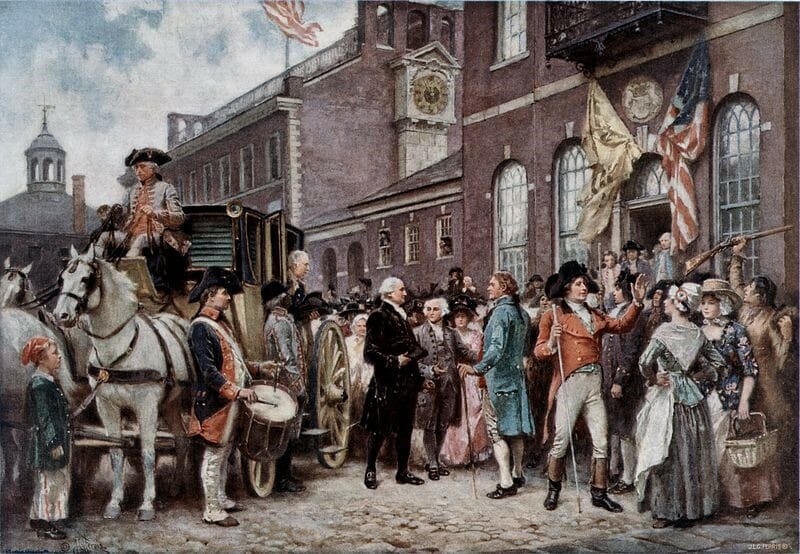

If President Washington was such a unifying force, why were the early 1790s so violent and contested? "Washington's Inauguration at Philadelphia" by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930).

"Washington's Inauguration at Philadelphia" by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930).

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the ninth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His wartime experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 9 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8.

* * *

“What a stupendous, what an incomprehensible machine is man! Who can endure toil, famine, stripes, imprisonment & death itself in vindication of his own liberty, and the next moment … inflict on his fellow men a bondage, one hour of which is fraught with more misery than ages of that which he rose in rebellion to oppose.” —Thomas Jefferson in a letter to John Adams (1816)

Close your eyes and imagine America as it was under the administration of President George Washington. No doubt, most readers would envision a heroic, tranquil time, when all was right and the great Founders ruled the United States as they had intended. It’s a comforting myth and, to be sure, a reflection of a closely held nationalist narrative: America may have faltered, may even have been off track at times, but once, under the steady hands of men like Washington, all was as it should be. How, then, are Americans to process the reality of the first president’s tenure—an age of turmoil, violence and division? Perhaps this: As Billy Joel sings, “The good old days weren’t all that good,” and as John Adams wrote, “Divided we ever have been, and ever must be.”

When Washington became president, no one was surprised. No other man had the fame, confidence or esteem to preside over the early American republic. Still, the former general inherited a fiercely riven nation, a republic that had only barely ratified the controversial Constitution. “Anti-Federalists,” or opponents of the Constitution, had not simply disappeared, and a significant mass of Americans distrusted the growing power of the central government.

President Washington would rule a union of states wildly different from the modern U.S. The West remained generally unsettled—populated and contested by still powerful Indian confederacies, led by the Miami in Ohio and the Cherokees/Creeks in the South. The U.S. was still mainly rural, with 80 percent of the population engaged in farming. Most farmers (including many Indian tribes) engaged in semi-subsistence agriculture, consuming much of what they grew but also relying on local trade and barter, as well as the purchase of products such as sugar, salt and coffee. On the Atlantic coast, of course, and in the larger cities, a sizable minority of Americans was increasingly tied to the national and international commercial economy. These two competing visions of the American Dream—rural versus more heavily populated areas—would remain in tension for decades to come.

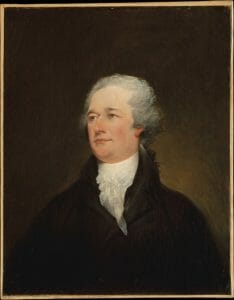

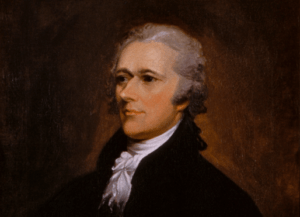

A Question of Fairness: Alexander Hamilton’s Economic Program

“[I have] long since learned to hold popular opinion of no value.” —Alexander Hamilton

No one better reflected the commercial and national centralization mindset than the West Indian-born bastard (and notably self-made man) Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. It is curious that one of such humble circumstances would not only rise to such prominent heights but espouse such an aristocratic agenda. Nonetheless, for better or worse, Hamilton—now the title character in an acclaimed Broadway hip-hop production—would dominate the economic (and political) policies of the Washington administration.

Oddly, however, the state (and economy) that Hamilton envisioned for the U.S. was most similar to that of Britain, which he called “the best [government] in the world.” Sure, the Americans had revolted against the mother country, but now, according to the treasury secretary, it needed to model itself after the old empire. Hamilton promoted banks, federal power and, most controversially, the funding and assumption of state debts.

Remember back to the Revolution when soldiers and merchants were paid in near-worthless Continental paper currency. For fear of starvation and penury, most veterans had little choice but to sell their bills and bonds to wealthy speculators at just a fraction of face value. Now, said Hamilton, the new federal government should assume all state debts—thereby eliminating the need for most state-level taxation—and fund, or pay out, the full face value of the bonds and Continental currency in speculators’ hands. Though the states were grateful for the debt relief and citizens appreciated the steadily decreasing rates of local taxation, the plan for funding and assumption was controversial from the start.

It is easy to see why. Economics is rarely a simple matter of dollars and cents, of reason and records. There is also a moral component—even today—along with a sense of the need for justice in public economy. Why, many former soldiers and farmers asked, should already affluent speculators and stock-jobbers receive such a windfall from the government? Why should hard-earned tax dollars pay the printed value, rather than the fair market value, of the inflation-prone Revolutionary currency? Shouldn’t, as now Hamilton opponent James Madison argued, the government make a distinction between the original holders of the notes and the speculating elites now in possession of most outstanding bonds?

To modern, especially populist ears, these questions seem reasonable—just, even. Nonetheless, Hamilton argued that in order to develop confidence in the market and earn international credit and standing, the U.S. must fund the bonds at face value and not distinguish between current and original owners. The funding dispute that arose may seem a slight matter to modern readers, but an understanding may be gained by comparing it with the argument over the Wall Street bank “bailouts” of 2008 and 2009 at the start of the Great Recession. Furthermore, to understand the passion of the funding debate, consider that upward of 40 percent of federal revenue in the 1790s went to pay interest on the funded debt.

Hamilton’s position came to reflect that of most Federalists—mostly wealthy, urban types who were early proponents of the Constitution. In order to succeed, Hamilton believed, the government must primarily associate and concern itself with the wealthy, commercial elites. Hamilton held a strong belief that human nature was fundamentally selfish and thus there was no other course for a successful government than to fix its hopes on the affluent. Hamilton, of course, was on shaky constitutional ground. But he never wavered. The treasury secretary argued that the Constitution granted the federal government implied as well as enumerated powers, manifested in the “necessary and proper” clause.

Not everyone agreed. Secretary of State Jefferson and many rural, former Anti-Federalists felt that the Constitution did not explicitly authorize Hamilton’s program and that federal powers should be strictly limited for the protection of the masses. After all, they exclaimed, didn’t we just wage a revolution against such policies? The opponents of Hamilton and his centralizing fiscal programs crafted an identity similar to the “country” Whigs of Britain and began to label Federalists with the notorious pejoratives “Tory” or “loyalist.”

Indeed, differing economic interests often linked to political interests and factions in the new republic. The commercial world of urban, coastal elites required an efficient transportation network and new roads for the rapid movement of goods into and out of the interior. Taxes, banks and the funding of debt would be required to generate the requisite investment. Those living in the semi-subsistence, rural world feared central power and were suspicious of “city values,” and most of these folks wished mainly to be left alone. Sound familiar? Indeed, this rural-versus-urban and cosmopolitan-versus-provincial conflict is still waged today. Exhibit one: the 2016 presidential election.

Aftershocks of Revolution: Explaining the Whiskey Rebellion

“An insurrection was announced and proclaimed and armed against, and marched against, but could never be found.” —Thomas Jefferson in a letter to James Monroe (May 26, 1795)

Consider the sketch and the photo above. The drawing depicts a riotous mob brutalizing and terrorizing a tax collector via the tried-and-true, all-American tactic of tarring and feathering. The image is similar to many depicting the struggle against British imperial taxation during the Revolutionary era. However, the scene depicted in this illustration is in Pennsylvania, and occurs a decade after the end of the War of Independence. The taxman is an American, a citizen of the United States, being tortured during the Whiskey Rebellion.

The photograph below the drawing depicts a modern American’s protest against the perceived excesses of federal taxation in 2009. Indeed, in what would come to be known as the tea party movement, many thousands of Americans—often in Colonial-era garb—took to the streets in that most American of public rituals: an anti-tax protest.

Anti-tax and anti-federal sentiment is as American as apple pie and still very much with us. But let’s return to the 1790s. Remember that Hamilton’s economic program, especially funding and assumption of state debts, would require significant federal revenue, even to pay the requisite interest. From where would this money come? Customs revenues, mainly, from taxes on imported goods entering the many natural harbors of the East Coast, but also from land sales, which would soon become possible with the conquest of Kentucky and Ohio. Still, neither source of income was sufficient, and thus Hamilton recommended an excise tax on distilled whiskey.

The western farmers along the Appalachian frontier—who often distilled their excess grain into whiskey for barter and sale—would bear the brunt of this new taxation. And, with a dearth of hard currency, these rural folk were perhaps the least equipped to pay it. Still, over the vigorous protests of the westerners, the Washington administration levied the tax in 1790.

The affected parties did not easily acquiesce. Most simply ignored the legislation and refused to pay. In western Pennsylvania, however, farmers in four counties openly defied the law, forming “committees of correspondence” (like the earlier anti-British patriots), terrorizing excise officers (in another rerun of the 1760s and ’70s) and closing the federal courts (ala Daniel Shays’ rebellion). To the rebels, the far-away Congress had no more right to tax them than had the Parliament in England. They sent petitions to Congress, formed local opposition assemblies and referred to the feds as “aristocrats” and “mercenary merchants.” Here was a semantic struggle for the soul of a new nation.

In other words, matters in western Pennsylvania and up and down the frontier weren’t unprecedented. Nevertheless, something had changed. Those protested against were now Americans, and the states were now governed by Washington’s post-constitutional administration, based just a few hundred miles to the east in Philadelphia. President Washington and the Federalists, fearing that the whole constitutional order might collapse, responded forcefully. In August 1794 the president donned his uniform and led an army of 13,000 federalized militiamen—a force larger than any he had commanded in the Revolution—and marched west. This was the first and last time a U.S. president would directly and personally command troops in a time of war or rebellion. How difficult it is, indeed, to picture a contemporary president leading a similar procession toward battle.

The Whiskey Rebellion was the single greatest incident of armed resistance to federal authority until the Civil War, yet the rebels dispersed as quickly as they had gathered once faced with Washington and his massive army. What matters, however, is that it happened at all; that rural unrest remained a powerful force—one that would be reaped by later political parties. Also significant was Washington’s response. The first president took the threat of rebellion and fracture very seriously. He knew the shakiness of the new republic and sought to send a message to the rebels. And send one he did, a rejoinder that Revolutionary War-era protests were no longer acceptable, that there would now be severe limits on public opposition to federal policies and, ultimately, that the government in Philadelphia (and later Washington, D.C.) was the supreme law of the land.

Conquering Ohio: The U.S. Army, “Mad” Anthony Wayne and a Doomed People

“Civilization or death to all American savages!” —A popular military toast of the 1790s

A great portion of early federal revenue was allotted to interest payments on the funded debt associated with Hamilton’s economic program. Most of the rest, however, paid for the U.S. Army to wage war on Indians in the Ohio Country. Indeed, the first half of the 1790s saw some of the most vicious and contested native warfare in American history. Strangely, few Americans now know of the battles of this era.

The United States’ hold on the western territories (between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River) granted to the new republic in the Treaty of Paris (1783) was extremely tenuous. Spain closed the Mississippi River at New Orleans to American traffic and also tried to attract the loyalty of settlers in Kentucky and Tennessee to the Iberian crown in Madrid. The British army refused to vacate forts in the Ohio Country and continued to arm and support a growing native confederation still (understandably) hostile to American expansion.

However, in the face of these facts and despite the best, if paltry, efforts of the federal government to regulate and organize the settlement of the fertile lands north of the Ohio River, land-hungry pioneers flooded the territory, often refusing to pay for land and setting off conflict with the local native tribes. It was a mess, as hasty expansion often is. In order to sell the land, systematize the settlement and attract respectable, law-abiding colonizers, the Washington administration realized it would have to force peace—through conquest or surrender—on the Indians.

The natives, some 100,000 of them in the trans-Appalachian west, had other ideas. They had not been present in Paris or acceded to Britain signing over their homelands to the nascent American settlers’ republic. They would not capitulate easily or bargain away their independence. They had taken notice when the U.S. Senate ratified a treaty (the nation’s first) with the southern Creek Indians, and then the corrupt Georgia Legislature promptly broke it. In Ohio, it was to be war.

The problem for Washington was the diminutive, untrained, ill-disciplined army at his disposal. Though growing under the policies of Hamilton, the Army proved feeble in early efforts to bring the natives to heel. In 1790, Gen. Josiah Harmar led some 1,500 regulars and militiamen into the northwest Ohio Country. They were defeated in several small skirmishes, with heavy casualties, in the vicinity of present-day Fort Wayne, Ind. The next year, Gen. Arthur St. Clair led some 1,400 troops and militia to a disastrous fate. On Nov. 4, 1791, his unprepared troops were surprised and vanquished by 1,000 Indians commanded by the Miami chieftain Little Turtle. Six hundred soldiers were killed in by far the largest defeat ever in the U.S. history of Indian wars. To mock the Americans’ land hunger, the natives stuffed soil in the dead men’s mouths. It was a national humiliation.

Washington proceeded to build a professional standing army of 5,000 troops and doubled the military budget. A Revolutionary War hero, Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne, then took two full years to train his newly dubbed “American Legion” before decisively defeating the Indian confederation at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, near the site of present-day Toledo, Ohio. The British refused to save their Indian allies, as they were not willing to risk war with the American republic (they were already busy combating revolutionary France). The defeat and lack of external support sealed the fate of Ohio Country Indians and broke their resistance for another two decades.

The results of Wayne’s victory were immediate and profound. Native tribes submitted or moved westward, and the white settler population exploded. What had been decidedly Indian land just a few years earlier quickly resembled the white man’s land of the East Coast. Between 1790 and 1820, Kentucky’s population grew by a factor of eight. Ohio’s population also grew rapidly. Still, something far more fleeting was lost: the age of eastern Indian independence, an era when native tribes had often been able to play one European empire against another. The frenzied Americans’ desire for land ultimately posed a greater threat to native autonomy than that of any of the other European imperialists. The growth of the United States—a nation purportedly devoted to the equality of man—spelled the end of a very old and unique Native American culture.

Better Hell Than Party: The Development of Federalist and Republican Factions

“If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.” —Thomas Jefferson, 1789

“Nothing could be more ill-judged than that intolerant spirit which has, at all times, characterized political parties.” —Alexander Hamilton, 1787

It wasn’t supposed to happen. Everyone, it seemed—including President Washington—opposed and feared the formation of political parties, or “factions” as they were often called. Still, the development of political blocs should have come as little surprise. Just as the republic remained divided between proponents and opponents of the Constitution, so Washington’s own Cabinet was split. The secretary of the treasury, Hamilton, desired that the U.S. become a centralized, British-style fiscal-military state; meanwhile, Secretary of State Jefferson had become the unofficial leader of numerous skeptics who feared and distrusted the federal government. Neither was initially willing to admit it, but these two foes quickly became the de facto heads of the Federalist and Republican parties, respectively.

The two emergent political parties had both a domestic and international component. Domestically, the Federalists represented wealthy, urbane holders of proprietary wealth and sought centralization of debts, finances and power in the federal Capitol. Hamilton was their intellectual muse, even if the staunchly anti-party George Washington emerged as their leader. The Republicans, under the de facto direction of Jefferson, represented more Southern, rural and agricultural interests and sought low taxation and minimal government interference. Jefferson, in fact, portrayed the contest as being not between two discrete political parties but between “aristocrats” (Federalists) and republican “defenders of the Revolution.”

The battle was both public and personal. The two men could not have been more different, and, given their divergent backgrounds, one might regard each as more suited to the opposing faction. Instead, in a bit of historical irony, the low-born son of the Caribbean, Hamilton, brought the poor man’s chip on his shoulder to the leadership of the more elitist party. Jefferson, on the other hand, a classically aristocratic gentleman of the South, crowed on about the “common man” and radical republicanism. History, indeed, is often stranger than fiction. Still, despite the underlying animosity, neither Hamilton nor Jefferson can be considered party leaders in the modern sense. In the world of the late 18th century, true “gentlemen” stood above politicking or campaigning, and relied on sometimes subtle literary attacks and the backing of allies and less prominent partisans.

The contours of this schism—of a kind still seen in our own day—would soon set off a few decades’ worth of political combat. Less remembered is the international component. The United States, after all, was never, and will never be, an island unto itself. In the early 1790s, just about all of the European Western World became embroiled in what would become a two-decade war with revolutionary France—which had ousted a king and declared a republic in 1789. Jefferson’s Republicans favored France in the ensuing global war, and, indeed, many staunch advocates of the revolutionaries argued (not without some merit) that America’s 1779 alliance with France obligated the U.S. to aid the burgeoning republic in its wars.

Thomas Paine, the famous author of the American Revolutionary tract “Common Sense,” considered himself an early-stage “citizen of the world” and, being the professional revolutionary he was, went to serve in the new French National Assembly. Jefferson, too, was remarkably radical—at least in correspondence—in his support for France. Even after the French Revolution executed the king and beheaded tens of thousands of “counterrevolutionaries,” Jefferson remarked:

The liberty of the whole earth was dependent on [the French Revolution] … and … rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it is now.

The Federalists, though initially sympathetic to their old allies and brother republicans, were soon more circumspect. They feared the radicalism and resultant bloodshed of the French Revolution and, if anything, began to favor their British cousins. Essentially, the wars of Europe polarized political factions across the Atlantic. Passions ran high and partisan divisions deepened.

We should, perhaps, be unsurprised that political parties quickly formed in the United States. This was a highly literate and literary culture, with widespread property ownership, a broad franchise (or voting rights) for white men, and many newspapers. These were litigious people, concerned with law, governance and societal mores. In that sense, despite the politicians’ regular proclamations to the contrary—so common in the 18th century—America was the perfect place for parties and factions to form. This was, in a way, the unintended consequence of the colonists’ revolution. Rebellion is messy—just ask today’s Arabs!

Vital Precedents: The Critical (if Flawed) Character of George Washington

“The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissention … is itself a frightful despotism … sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.” —George Washington

Washington owned slaves (though he freed them upon his death), he had ordered mutineers shot during the war and was by some measures the wealthiest man in all of America. Still, it is doubtful that any other citizen could have held the early republican experiment together. In his day, Washington epitomized public virtue and selflessness. Notoriously thin-skinned and ever cognizant of his reputation, Washington worked hard to bolster this image. Though he had become affiliated with the Federalist faction while serving as president, Washington aspired to be the disinterested arbiter of national affairs. He was certainly seen that way by most Americans; even his critics were loath to publicly disparage the president. It was often said that Washington was denied children of his own so that he could be the “father” of his country. And, indeed, he was.

It was assumed that Washington, like Polish kings of the era, would be elected but serve for life—an elective monarch. When the new president appeared in public, bands often played “God Save the King.” And, indeed, Washington was an aristocrat of sorts, a self-styled gentleman. He believed in the social hierarchy and mores of the Colonial era and firmly held that some men were born to rule, others to obey.

Nonetheless, it is to Washington that the U.S. republic may owe its greatest thanks. This man, this figurehead and celebrity of the Revolution, set many precedents as chief executive that have stood the test of time. Few of his successors dared to defy the unwritten codes Washington had set. He did not accept a crown though there were moments he might well have become a king; he stood apart from much legislative business and respected the prerogatives of Congress; he kept the U.S. out of foreign wars and, indeed, warned against entanglements in fixed alliances or other nations’ conflicts.

Most importantly, however, he left. After two terms, though he was not legally obliged to do so, Washington chose to step down, retire, and allow for a new presidential election. Had he not, it is doubtful that any of his successors would have done so and the U.S. may very well have mutated into a British-style constitutional monarchy. As it was, 30 consecutive executives followed the Washington precedent, and only after Franklin D. Roosevelt broke with the tradition in 1940 did a later Congress amend the Constitution to include presidential term limits. We cannot overestimate the significance of Washington’s decision.

* * *

Be that as it may, it was a divided nation that Washington would pass along to his successors. A nation cleaved into increasingly oppositional factions of Federalists and Republicans; a nation at the brink of war with Britain, France, Spain or some combination of the three; a nation still engaged in westward conquest and fierce combat with Native Americans; and, of course, a nation uncertain as to its future.

Though Washington has lent his name to currency, schools, cities and parks, it is a sadly ironic truth that most of the stoic warnings from his farewell address were quickly ignored. Within four years of his retirement, bitterly oppositional political parties brought the nation close to revolution (are we not approaching something similar today?). By 1812 the U.S. would wage an indecisive war with Britain, and in the 20th century it would sign on to multiple, permanent foreign alliances of precisely the sort Washington feared. What, then, would the first president think of NATO, or modern America’s relationship with Israel or Saudi Arabia?

If Washington held the new country together, it was only just so—a near-run thing. So close your eyes again, reimagine America’s first presidential administration, and this time consider the precariousness of the American experiment.

Open your eyes. Flip on CNN.

It is precarious still.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

● James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle, and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 9: “The Early Republic, 1789-1824” (2011).

● Gary B. Nash, “African Americans in the Early Republic,” OAH Magazine of History 14, No. 2 (Winter 2000).

● Gary B. Nash, “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America” (2005).

● Gordon Wood, “The Significance of the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 8, No. 1 (Spring 1988).

● Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815” (2009).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.