American History for Truthdiggers: Birth of an ‘Era of Revolutions’

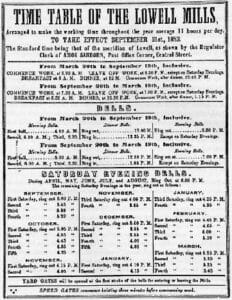

On the heels of the War of 1812, society began to drastically change due to government action and technological innovation. As some Americans prospered, many were left to wither. A fragment of "Pat Lyon at the Forge," an 1826-27 painting by John Neagle. In commissioning this portrait, the wealthy businessman instructed that he be depicted as a workingman and not a gentleman. The well-known image is considered reflective of societal changes occurring in the United States at the time.

A fragment of "Pat Lyon at the Forge," an 1826-27 painting by John Neagle. In commissioning this portrait, the wealthy businessman instructed that he be depicted as a workingman and not a gentleman. The well-known image is considered reflective of societal changes occurring in the United States at the time.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 13th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 13 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12.

* * *

It was a time of great change. And, as always, a picture—or in this case a painting—is worth a thousand words. In the portrait above, Patrick Lyon of Philadelphia is depicted as a blacksmith hard at work at the forge. He wears an apron and a shirt that shows his muscular forearms. This portrait was commissioned by Lyon himself, and it depicts a man proud of his labor, toil and strength. Here was a working man—blue-collar chic!

This is stranger than it may appear to modern eyes. After all, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, men who could afford to commission such paintings usually preferred to be portrayed in formal dress, adorned in powdered wig and leggings and surrounded by the expensive objects that implied an aristocratic status. Something had changed.

Lyon may appear to be the quintessential workingman in this painting, but he was also something else—one of the wealthiest men in Philadelphia. He was a leading businessman, an inventor and, yes, long before, a blacksmith. Pat Lyon possessed more than the requisite means to commission the ubiquitous aristocratic portrait, yet instead chose to be represented as a simple—yet proud—blacksmith. In contrast to his aristocratic peers and forebears, Lyon explicitly told the artist, John Neagle (1796-1865), that he did “not wish to be represented as what I am not—a gentleman.”

There was something profound afoot in American society in the three decades following the War of 1812, a veritable revolution of revolutions—massive changes in economics, politics and society. Neagle’s portrait of Pat Lyon in many respects depicts them all. The United States was becoming more commercialized, more egalitarian (at least for white males) and, to a certain extent, populist. The Federalists, seen as the party of aristocracy, had faded from the political scene, and new factions of the Republican Party would lead America through this time of turmoil.

Technology, infrastructure, government investment and communications: These would all permanently change. Quality of life for most Americans increased, but others, as always, were left behind—victims of a society moving too far too fast. This and the next two volumes of this series should be seen as interacting parts of the same holistic volume, about an era of revolution.

Lessons of War: Madison, Republicans and the Hypocrisy of ‘New Nationalism’

The War of 1812 was at best a draw, at worst an embarrassing debacle. It demonstrated the unpreparedness of American arms, government and infrastructure for conflict with a major world power. The United States, despite major efforts, couldn’t even conquer Canada and was lucky to maintain its own territorial integrity.

Nonetheless, James Madison (in the presidency from 1809 to 1817) and most Americans, especially Republicans, decided to publicly rebrand the war as a decisive victory, a Second War of Independence. What we know as nationalism—a term not in use until the 1830s—exploded in the aftermath of this indecisive war. If America could defeat mighty Great Britain, again, what couldn’t it do? The entire continent seemed ripe for the taking, and, in due time, for the improving. In time Spanish Florida would be illegally invaded by Gen. Andrew Jackson and eventually would be sold to the U.S. by a Spain that did not have much choice in the matter. The Pacific Northwest would be divided and shared between Britain and the U.S., making America a two-ocean power and cutting the Spanish and Russians out of the deal. All, it seemed, was part and parcel of America’s unmistakable destiny.

Yet the men who had stood atop the federal government throughout the war privately knew better. They were aware of the debacle that had ensued and how near disaster had been. The war had been fought on a shoestring and, generally, under the republican ideology of limited government. The Republicans, from Thomas Jefferson to Madison, had espoused a minimalist approach to federal power, but that would change.

Soon the only party that had any real power—the Republican Party—began to fragment into opposing factions and eventually would become nearly unrecognizable. Suddenly Madison and the “new nationalists” began calling for internal improvements (canals and roads), military preparedness (this time the Army would not be completely demobilized), a protective tariff to benefit manufacturers, and even a re-chartering of the National Bank. Every one of these demands had recently been anathema to the doctrinaire Republicans, including the father of the party, Jefferson. What’s amazing is how quickly most—including the sage of Monticello—embraced the changes and accepted the increase in federal power and jurisdiction.

Wars change societies; they always have and surely always will. Things are gained—efficiency, technological innovations and federal power—but things are also lost, such as civil liberties, ideological purity and, in the case of America, modesty.

A Society Forever Changed: The Transportation and Commercial Revolutions

“We are under the most imperious obligations to counteract every tendency of disunion. … Let us, then, bind the republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space.” —Congressman John C. Calhoun of South Carolina

It is ironic how many modern conservatives tend to blame government action for all problems and extol the virtue of private entrepreneurship and innovation. How rarely are those two sections of society so discrete and separate. The transportation and commercial revolutions that unfolded in 19th-century America did forever alter (usually for the better) life in these United States. Commodity costs dropped, travel became affordable, information proliferated and living standards rose. This—under the 16 years of Madison and Monroe’s administrations—was possible only through the combination of Republican governmental investment and prioritization of private innovation. The once laissez-faire Republicans ever so quickly pivoted from small government to the funding and application of technological inventions in cooperation with the private sector.

This was a team effort, and it forever altered life in America. Nearly everyone was affected by the proliferation of steamboats, canals, roads and technological advances. Everyone, even Native Americans, became more tied to the commercial economy. Fewer farmers were needed, and other occupations and professions opened up. There were now both more wage laborers and commercial entrepreneurs. This meant that property ownership—once the signal indicator of wealth and status—became less influential in economic and political life. It wasn’t long before most states eliminated property qualifications for voting.

A prime example of innovation, government investment and societal change unfolded in New York. In the 1820s, after years of work, the Erie Canal was completed. Running 363 miles from the Hudson River to Lake Erie, the 40-foot-wide canal connected the farms of the Great Lakes and Midwest with the trading port of New York City. Almost overnight the population of that city, and of western New York state, exploded. New York became, forever, the singular commercial hub of the United States. Local farmers and merchants were now plugged into a nationwide and international economy. As the historian Daniel Walker Howe noted, “New York had redrawn the economic map of the United States and placed itself at the center.”

The commercial and transportation revolutions set off a communications revolution that sped up time and the flow of information. Mail traveled exponentially more quickly and so did newspapers, the primary items of mail in those days. The number and diversity of papers expanded, bringing politics and international affairs into the daily lives of more and more Americans. But there was, undoubtedly, a dark side to this information propagation. Most newspapers in this era were little more than organs of particular political parties or factions, rather than objective news sources. These papers relied, oftentimes, on wealthy benefactors or government printing contracts from the party in power. The next time someone complains about the unprecedented partisanship and corporate influence on today’s media space, remind them of this era of the Market Revolution, the period of intense economic and communication revolutions in the years following 1815.

Winners and Losers: The Uneven Effects of the Market Revolution

“And if we look to the condition of individuals what a proud spectacle does it exhibit! On whom has oppression fallen in any quarter of our Union? Who has been deprived of any right of person or property?”—President James Madison

The crazy part is Madison probably meant it. As the chief executive waxed eloquently on the triumphs of technology and his own administration in the above quote, he seemed truly and honestly unaware of how obtuse a statement this was in the second decade of the 19th century. This was, however, a time when few would respond to the president by pointing out the hypocrisy of holding some 1.5 million blacks in chains, keeping several million women trapped in the paternalistic home, and having stolen the lands of hundreds of thousands of Native Americans.

Such was the spirit of the times that a “republican” such as President Madison would scoff at such critiques—after all, those folks didn’t count in his visions of democratic utopia. And so, left behind in this great rising market tide were natives, blacks, many women and some impoverished white workers.

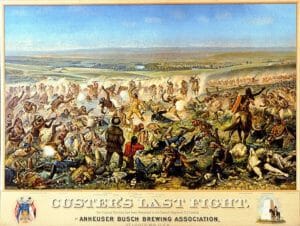

Native Americans, once again, can be seen as some of the great losers in the Market Revolution era. More roads, more canals and quicker transportation meant, simply, more white settlers expropriating their tribal lands even faster. The technology and transportation were not for them.

In some cases, even natives living beyond the borders of the United States were affected by American triumphalism. The “hero” of the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson, had during the conflict seized lands from the Creek Indians, even those who had fought on his side. This opened Alabama and Mississippi for immediate settlement. Only this wasn’t enough. In 1818, President James Monroe sent him on a punitive expedition (with unclear orders) into Spanish Florida, to punish natives and allied runaway slaves who had exploited the international border to raid American settlements. The weakened Spanish Empire was powerless to stop him.

Jackson’s main opponent was a breakaway sect of Creeks who had moved south and intermixed with runaway slaves and marooned blacks to form the famous Seminole tribe. Jackson burned settlements, chased the warriors south, seized some Spanish forts (without a fight) and then refused to leave! He even arrested and executed two British traders as “spies” in contravention of international law and caused a diplomatic scandal. Eventually, of course, the Spanish ceded the Floridas to the U.S., and, of course, native power was forever broken in the old Southwest (the present states of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana).

Blacks, slaves, fed the new market economy; they rarely benefitted from it. Contrary to popular conception, Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin (short for “engine”) did not lessen the burden of slave pickers but instead increased their expected yield and workload. Now that the seeds could be separated from raw cotton more quickly, the cotton demand exploded. Furthermore, the temperate climate and limitless land in what was then considered the southwest (stolen from the Creek and other native tribes) made the United States the top producer of cotton in the world by 1820. It was cotton that made America, and the South, “king.” It fed the textile plants of England and Massachusetts alike, and the demand seemed insatiable.

Slaves were expected to work harder, rest less often and produce more. Worse still, the massive migration southward and westward (one of the most significant in American history) of farmers and planters from Virginia, Maryland and the Carolinas to Alabama and Mississippi also meant the concurrent shift of slaves. With Virginia tobacco less profitable, Chesapeake planters had less need for their slaves. Thus, over the proceeding decades—and up until the Civil War—men from the Upper South sold slaves, broke up their families and fed the “Alabama fever,” as it was known. The black experience, of forced migration and family separation, cannot be detached from the triumphs of the Market Revolution.

* * *

“I went in among the young girls [at the Lowell Mills in Massachusetts] … not one expressed herself as tired of her employment, or oppressed with work … all looked healthy … and I could not help observing that they kept the prettiest inside. … Here were thousands … enjoying all the blessings of freedom, with the prospect before them of future comfort and respectability.”—Col. and Congressman Davy Crockett, on visiting the Lowell Mills textile plants

Crockett, the veritable “King of the Wild Frontier,” was right about one thing. In Lowell, Mass., and other urban (usually Northern) settings, women were, increasingly, leaving the home and entering the workspace. What is interesting, and instructive, is the language this frontiersman used to describe these toiling women. They were, he said, free! This seems an odd way for a man of the wilderness, of the vast hardy Western frontier, to describe the life of dirty, cramped factory workers held (see below) to a rigorous dictatorship of the clock.

In the era of market and transportation revolutions, there was indeed now more economic opportunity, but there also grew a greater disparity between rich and poor (sound familiar?). For all the talk in this era of “self-made men,” most white males still toiled as small farmers or wage laborers. Only a tiny fraction accumulated immense wealth.

Some small farmers, often those who found themselves unluckily located away from the roads and canals, saw their business dwindle as the revolutions of commerce, transportation and economics literally passed them by. Many a part of New England and upstate New York became littered with ghost towns and abandoned farms. Many merchants and artisans went bankrupt, unable to deal with the competition of goods shipped in from afar.

There was also, some felt, a loss of independence, community and fulfillment produced by the market shift. Jefferson’s utopian dream of small, independent farmers from the Atlantic to the Pacific simply hadn’t panned out (as Jefferson woefully acknowledged late in his life). This, as we will see in a later volume of this series, led to an explosion of religious, social and temperance revivals—attempts to reconnect a world on the move with the cherished values of the “old way.” This, too, seems a natural outgrowth of all such economic and political revolutions in American history.

* * *

It was a strange time; one of speed and change; of winners and losers; of growth and of pain. It was the time of Pat Lyon—the rich man who had himself painted as a blacksmith—and of dislocated slaves pushed ever harder in the cotton fields. This was the era of a rising tide of wealth but also of child labor and the crowded women at the Lowell Mills.

What’s certain is that the economic, political and societal revolutions of 1815-1845 (which will be covered in the next two volumes) cannot be studied in isolation. This was an era of revolutions that interacted to forever change antebellum American society. Some prospered as others withered, but all were affected in kind.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 10: “The Opening of America, 1815-1850” (2011).

• Daniel Walker Howe, “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848” (2007).

• Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815” (2009).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.