American History for Truthdiggers: Original Sin

Our society descended from colonial Virginia's sinister caste system, in which race, class, labor and slavery were inextricably linked. The swampy environs of Jamestown, Virginia, claim the life of another 17th-century English settler in this painting by National Park Service artist Sydney King. (National Park Service / Public Domain)

The swampy environs of Jamestown, Virginia, claim the life of another 17th-century English settler in this painting by National Park Service artist Sydney King. (National Park Service / Public Domain)

Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

The “American History for Truthdiggers” series, which begins with the installment below, is a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His wartime experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

American Slavery, American Freedom (Colonial Virginia 1607-1676)

Origins matter. Every nation-state has an origin myth, a comforting tale of trials, tribulations and triumphs that form the foundation of “imagined communities.” The United States of America—a self-proclaimed “indispensable nation”—is as prone to exaggerated origin myths as any society in human history. Most of us are familiar with the popular American origin story: Our forefathers, a collection of hardy, pious pioneers, escaped religious persecution in England and founded a “new world”—a shining beacon in a virgin land. Of course, that story, however flawed, refers to the Pilgrims, and Massachusetts, circa 1620. But that’s not the true starting point for English-speaking society in North America.

The first permanent colony was in Virginia, at Jamestown, beginning in 1607. Why, then, do our young students dress in black buckle-top hats and re-create Thanksgiving each year? Where is the commemoration of Jamestown and our earliest American forebears? The omission itself tells a story, that of a chosen, comforting narrative (the legend of the Pilgrims), and the whitewashing of a murkier past along the James River.

The truth is, the United States descends from both origins—Massachusetts and Virginia—and carries the legacy of each into the 21st century. So why do we focus on the Pilgrims and sideline Virginia? A fresh look may help explain.

The Age of ‘Discovery’

When it comes to history—like any story—the starting point is itself informative. I taught freshman history at West Point, a far more progressive and thoughtful school than many readers probably imagine. Nonetheless, with cadets required to take only one semester of U.S. history, we had just 40 lessons to illuminate the American past. So where to start? The official answer—as in so many standard history courses—was Jamestown, Virginia, 1607.

That, of course, is a fascinating, perhaps absurd, choice. Such a starting point omits several thousand years of Native American history, of varied, complex civilizations from modern Canada to Chile. Time being short and all, 1607 remains a common pedagogical starting point. As a result, from the beginning, our understanding of U.S. history is Eurocentric and narrow (covering only the last 400 or so years). Consider that Problem No. 1.

Next, contemplate the language we use to describe the “founding” of new European colonies. This is, say it with me, the “Age of Discovery.” In 1492, Columbus discovered (even though he wasn’t first) America. Now, that’s a loaded term. Isn’t it just as accurate to say that Native Americans discovered Columbus—a lost and confused soul—when he landed upon their shores?

When we say Europeans discovered the “New World,” we’re—not inadvertently—implying that there was nothing substantial going on in the Americas until the Caucasians showed up. Europe has a dated, chronological history, reaching back at least to the Greeks, which most students learn in elementary school and later on in Western Civilization classes. Not so for the Native Americans. Their public history starts in 1492, or, for Americans, in 1607. What came before, then, hardly matters.

Inauspicious Beginnings

Englishmen came neither to escape religious persecution nor to found a New Jerusalem. Not to Virginia, at least. No, the corporate-backed expedition—by the Virginia Joint Stock Company—sought treasure (think gold), to find a northwest passage to India, and balance the rival Catholic Spaniards. But, first and foremost, they pursued profit.

The expedition barely survived. That should come as little surprise. They chose a malarial swamp for a home. The first ships carried mostly aristocrats—“gentlemen,” as they were then labeled—with a few laborers and carpenters for good measure. Gentlemen didn’t work or deal with the dirty business of farming and settling. But they did like to argue—and there were too many “chiefs” on this voyage. The first party did not include any farmers or women. Only 30 percent survived the first winter. Two years later, only 60 out of 500 colonists survived the “Starving Time.” Over the first 17 years, 6,000 people arrived, but only 1,200 were alive in 1624. One guy ate his wife.

So why the disaster? Why the poor site selection and early starvation? First off, the colonists chose a site inland on the James River because they feared detection by the more powerful Spanish. But mainly the disaster came down to colonial motivations. Jamestown was initially about profit, not settlement. Corporate dividends, not community. This was the private sector, not a permanent national venture. In that sense, matters in early Virginia were not unlike modern American economics.

Saved by Tobacco, the First Drug Economy

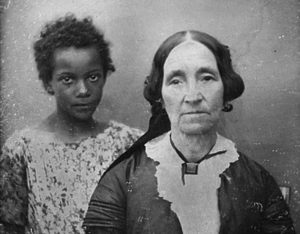

(Wikimedia Commons)

They never did find much gold, or, for that matter, a northwest passage. Then again, they didn’t all starve to death. Rather, the venture was saved by a different sort of “gold”—the cash crop of tobacco. Tobacco changed the entire dynamic of colonization and control in North America. Finally, there was money to be made. The Englishmen shipped the newest vice eastward and pulled a handsome profit in return. Our beloved forefathers were early drug dealers. More migrants now crossed the Atlantic to get in on the tobacco windfall.

The plentiful “gentlemen” of Virginia sought to re-create their landed estates in England. Despite significant early conflict with the native Powhatan Confederacy, large tobacco plantations eventually developed along the coast. Who, though, would work these fields? Certainly not the landowners. The burgeoning aristocracy had two choices: lower-class English or Scots-Irish indentured servants (who worked for a fixed period in the promise of future acres) and African slaves. Whom to choose? Unsurprisingly, ethics played little role, and cost was the defining factor.

When mortality was high in the colony’s early years, plantation owners favored the cheaper indentured (mainly white) servants. But as more families planted corn, kept cattle and improved nutrition, death rates fell and slaves became more appealing. After all, though expensive in upfront costs, slaves worked for life, and the slave owners got to keep their offspring. Nevertheless, for the first several decades, an interracial mix of slaves and servants worked the land in Virginia.

Bacon’s Rebellion and the American Future

The problem with the tobacco economy was one of space. To be profitable, cash crops require expansive acreage, and in Virginia this meant movement inland. This expansion set the Englishmen on a collision course with local Native Americans. Furthermore, what was plantation society to do about those indentured servants who survived and matriculated? Land would have to be found somewhere. (Though not near the coasts and early settlements. The “gentlemen” weren’t about to divide up their own large estates.) In order to maintain their chosen societal model—landed aristocracy—in which the wealthiest 10 percent possessed half the wealth and the bottom 60 percent held less than 10 percent of accumulated wealth, new land would have to be found further west—in “Indian territory.”

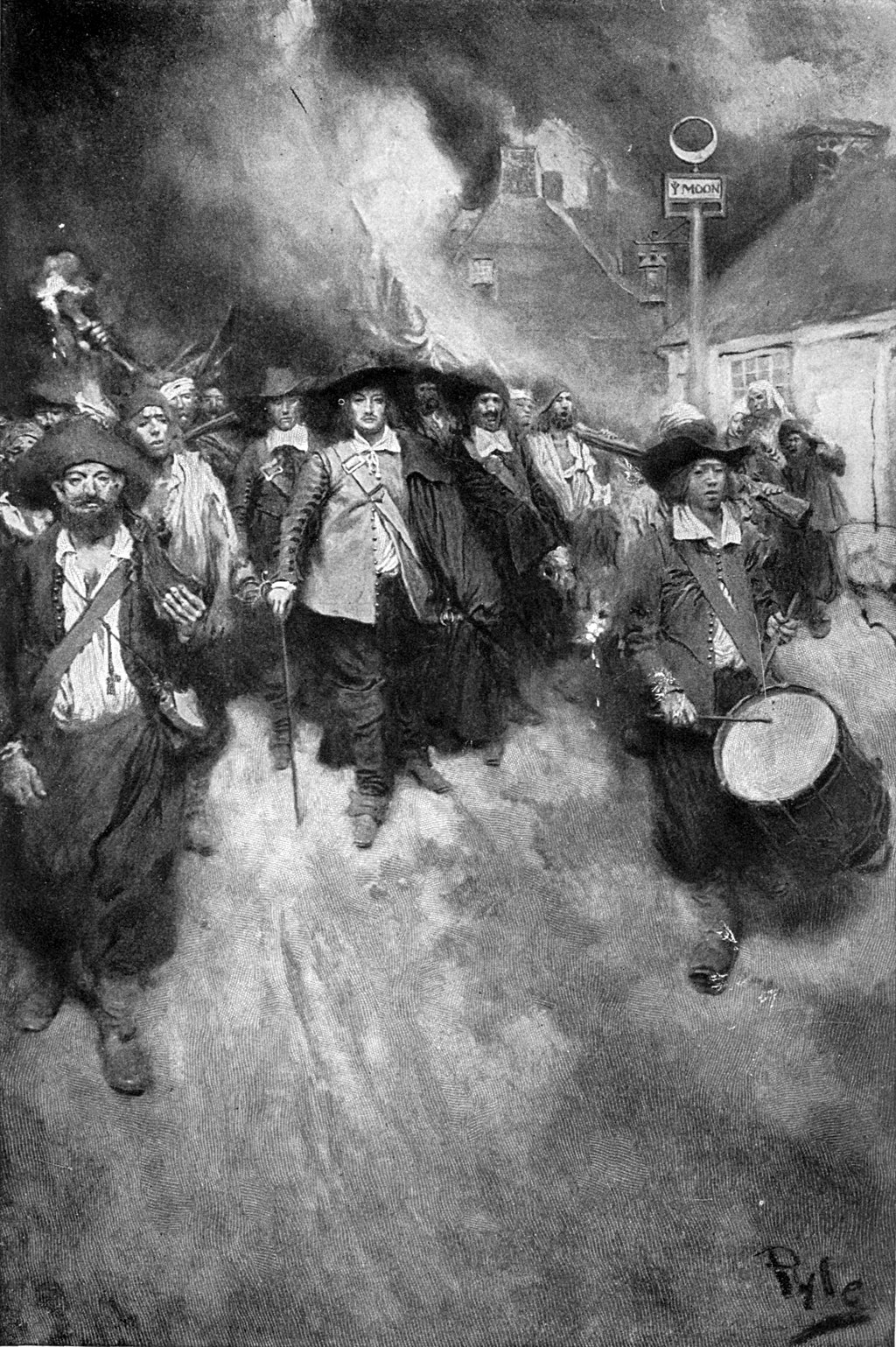

Thing is, after some bloody, early wars with the Powhatan, most “gentlemen” preferred a stable, secure status quo. (Not another war. That’d be bad for business.) However, falling tobacco prices, increased competition from nearby colonies and the relentless search by the former indentured class for more land brought frontier Virginians into conflict with an easy scapegoat: nearby Native Americans. Frustrated lower-class men—both white and black—rallied behind a young, discontented aristocrat, a firebrand named Nathaniel Bacon. Bacon led his interracial poor-people’s army in attacks on local Natives and, eventually, on Gov. William Berkeley and the establishment “gentlemen.” In 1675 and 1676, Bacon’s throng destroyed plantations and even burned Jamestown before Bacon died of disease (the “bloody fluxe”) and the rebellion petered out.

Bacon’s Rebellion was one of the foundational—and most misunderstood—events in American history. Here, a populist army savagely assaulted hated Native Americans and aristocrats alike. A mix of black and white former indentured servants demonstrated the fragility of Virginian society. The planter class was terrified. In order to avoid a repeat at all costs, the landed gentry made a devil’s bargain. To ensure stability, they realized they must co-opt some of the poor without ceding their own privileged status.

Enter America’s original sins: racism and white privilege. Plantation owners simply hired fewer indentured servants and became more reliant on (black) African chattel slaves for their labor force. The planters also threw a bone to the middling whites, lowering some taxes and allowing more political representation for white male Virginians.

The implications were as disturbing as they were enduring. White unity became the organizing principle of life in colonial Virginia. To be fair, poor whites lived difficult lives and always outnumbered their aristocratic betters. Nonetheless, these lower-class Caucasians benefited from the new, racialized social system. Pale skin became a badge of honor—life may not be optimal, but “at least we are white.” Black freemen became a thing of the past, and soon “blackness” became inseparably associated with slavery and the lowest of social classes. Black skin became a brand of slavery, and runaways could no longer blend into colonial society. Slaves were easily spotted by virtue of their color.

Bacon’s Rebellion linked land, labor and race together in nefarious ways. Land (ownership) remained the path to freedom. Labor remained essential to profiting from the land, and race came to define the relationship between land and labor. After 1676, a class-based system morphed into a race-based system of labor and social structure. The demand for African slaves rose and a triangular trade developed among North America, Africa and Europe. It seemed everyone benefited from slave labor—it became an Atlantic system. The American South had transformed from a society with slaves to a slave society. It would remain so for nearly two centuries. Race became a prevalent fact of life in the Americas—and still is, 342 years later.

What, then, do Jamestown and early Virginia have to tell us in 2018? Perhaps this: American slavery arose alongside and intertwined with American freedom. Our society descends from a sinister original sin: the development of a race-based caste system along the banks of the James River. Race, class, labor and slavery were inextricably linked in our colonial past. They remain so today.

This is the first installment in the ongoing “American History for Truthdiggers” series. A new chapter will be posted on Truthdig every other Saturday.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

● James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 3: “Colonization and Conflict in the South 1600–1750” (2011).

● Ira Berlin, “Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America” (2000).

● Edmund Morgan, “American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia” (1975).

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.