American History for Truthdiggers: FDR and His Deal for a Desperate Time

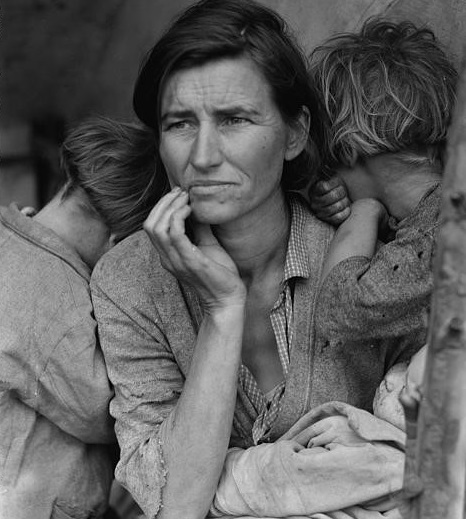

Our longest-serving president would leave a deep mark on the American psyche. But was he saint or villain, and what was his true legacy? A cropped version of Dorothea Lange's iconic image of Florence Owens Thompson and some of her children, photographed at a California migrant camp in 1936. "Migrant Mother," laden with trouble, would come to be seen as a depiction of the mood of a nation gripped by the Great Depression.

A cropped version of Dorothea Lange's iconic image of Florence Owens Thompson and some of her children, photographed at a California migrant camp in 1936. "Migrant Mother," laden with trouble, would come to be seen as a depiction of the mood of a nation gripped by the Great Depression.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 24th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 24 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23.

* * *

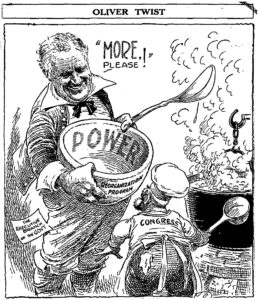

FDR was neither radical nor conservative, no matter what his defenders and critics claimed, both then and now. One part “traitor to his class” and another part defender of capitalism, he was both dangerously power hungry and the savior of American-style liberal democracy. This man was—like his party’s co-founder, Thomas Jefferson—an enigma, an unknowable sphinx. And yet he was the man for his moment. Indeed, FDR and his “New Deal,” as both a response to economic depression and reorganization of society, represent one of the most profound transitions in U.S. history. FDR served as president (1933-45) longer than anyone before or since, elected four times by wide margins. His opponents feared the man, and his supporters canonized him with rare and remarkable passion.

First elected in a landslide in 1932, the Democrat entered office loaded with expectations. Seen as the anti-Herbert Hoover (his Republican opponent for the presidency), Roosevelt sailed to a victory that many saw as an electoral rebuke to the conservative Republican regimes of his three immediate predecessors. Though it was difficult to know exactly just what his policies and ideology would be, the people placed their hopes and dreams in the 32nd president: He would, if nothing else, bring change. With the stock market crash of 1929, the economy crumbling and countless Americans out of work in the early years of the Great Depression, Roosevelt took office with the mandate for change and a public expectation of national salvation. Perhaps no man could live up to such demands. FDR would, over the next dozen years, experiment, tinker, triumph and fail. He knew the highest of political highs and the lowest of lows. Some historians and political scholars have even wondered, studying the maelstrom of conflicting Rooseveltian policies, whether FDR even had a coherent economic or political ideology. And they have a point.

What we do know is this: By the end of his second term, Roosevelt had forever transformed his own party, the American economy, the role and scope of federal power and, it can be said without exaggeration, the nation itself. Whether these changes were, in hindsight, for the better remains open to interpretation and debate. Indeed, today’s politicians, left and right, continue to battle over the legacy and ideals of this singular man. Perhaps a fresh look at the real Roosevelt—the man, the myth, the inheritance he handed down—will better illuminate the contours of today’s political combat.

A New Deal (to Save Capitalism?)

Roosevelt’s detractors labeled him a socialist before he ever took office. His partisans deified him ahead of his inauguration and predicted he would save the nation from economic plight and bring back prosperity. Roosevelt was, in fact, neither a “commie” nor a miracle worker, neither Christ nor Antichrist. What he was, as he took the mantle of executive power in March 1933, was imbued with a mandate for change and determined to do something—not just to end the Depression but to reshape the country. Through fits and starts, periods of immense popularity and stretches in the political doldrums, FDR would improvise and legislate with an energy and passion rarely seen from an American president.

From the very start, both on the campaign trail and in his inaugural address, Roosevelt announced that the train of change was a-coming. Accepting his party’s nomination in a Chicago stadium, he exclaimed, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” Just what that New Deal would mean in practice was initially rather vague, couched in rhetoric more than clear public policy. FDR liked to say that the “New Deal is as old as Christian ethics. … It recognizes that man is indeed his brother’s keeper. … [It] demands that justice shall rule the mighty as well as the weak.” To the optimistic leftist and the fearful conservative alike, this rhetoric smacked of socialism. But it was never that.

The New Deal would prove both less ideological and more restrained than its proponents and detractors ever surmised. Experimentation, rather than a coherent Marxist ideology—which some of the president’s enemies suspected—defined the New Deal. On the campaign trail in May 1932, FDR said as much, explaining, “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation … take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all try something.” Roosevelt was nothing if not practical and intellectually malleable. Once, responding to the campaign question “What is your philosophy?” he retorted “Philosophy? Philosophy? I am a Christian and a Democrat—that’s all.” It would prove an accurate self-description throughout most of his tenure.

What Roosevelt was, from the start, was inspiring and comforting. Whether through his soaring public speeches or his soothing radio addresses (the famed “fireside chats”), Roosevelt reassured the American people. In his inaugural address he famously intoned, “This great nation will endure as it has endured. … The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” The people found Roosevelt, for whatever reason, to be strangely and uniquely accessible. In his first week in office, FDR received 450,000 letters. The mail continued apace throughout his presidency, and he made time to read a selection daily. He saw himself, and was often portrayed as, the People’s President. As such, he repeatedly invoked his deeply held belief that society—and democracy—would fail to function if too many workers and farmers slipped into desperate poverty. Even before his election, he asserted that “[i]n the final analysis, the progress of our civilization will be retarded if any large body of the citizens falls behind.”

Assembling a “brain trust” of mostly progressive advisers—including Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, the first female member of a presidential Cabinet—FDR got to work. In his vaunted first “100 Days,” Roosevelt would push through emergency legislation meant to ease Americans’ suffering and begin the path to economic recovery. The Emergency Banking Act briefly closed the nation’s banks—a four-day banking “holiday”—and reopened them only once they had been declared sound. In a following flurry of legislation, he proposed, and Congress passed, the Glass-Steagall Act (which separated investment banking from personal banking); created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC); the Public Works Administration (the PWA, which oversaw 10,000-plus infrastructure projects); an agriculture bill that called for direct government payments to farmers who agreed not to produce certain crops, thus controlling overproduction; the Tennessee Valley Authority (the TVA, a public corporation that employed thousands to create public improvements in one of the nation’s more depressed regions); and the Civilian Conservative Corps (the CCC, which hired 250,000 young men for forestry, flood control and beautification projects). By the time the 100 Days were up, Congress had passed 15 pieces of legislation.

Perhaps most popular with “his” people was the new Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which increased, for the first time, direct federal unemployment assistance to the states. This “handout” or “relief” (depending on one’s point of view) was something President Hoover and his fellow Republicans had fiercely (and perhaps self-defeatedly) resisted. The result of FERA was profound. Roosevelt, the savvy politician, had “artfully transferred” the allegiance of the nation’s poor from their local leaders to the president and Washington, D.C.

Most transformative, though, was probably the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which abandoned Progressive Era “trust-busting” for the “cartelization” of major industries. The act would establish federal regulations on maximum work hours and child labor and guarantee the (limited) right of workers to unionize. The NIRA also empowered the government to oversee and control production in whole industries, and forced price and wage increases. Another component of the NIRA was to be the Public Works Administration, which undertook an ambitious federal construction program meant to get the unemployed back to work. In many ways, early New Deal legislation—especially the nationalistic CCC and the self-regulating cartels of the NIRA—would have pleased FDR’s boyhood idol, his cousin Theodore Roosevelt. It bore the hallmarks of TR’s own economic philosophy so very clearly.

Still, the results of the famed 100 Days were mixed. What historians would later call Roosevelt’s “First” New Deal halted a bank panic, authorized the greatest public works program in U.S. history and granted billions in federal unemployment relief. Most importantly, it buoyed the hopes of the people and infused them with Roosevelt’s own optimism and hope. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that this deluge of new laws lacked any coherent pattern or ideology. The early New Deal also maintained—rather than overthrew—capitalism, regardless of the hopes of some on the far left. And certainly it did not end the Depression, which would rage for many more years.

Expectations of a quick fix were, to be fair, unrealistic. Yet, from one (admittedly liberal) perspective, it is well that the First New Deal did not end the economic emergency outright. After all, had prosperity been restored by 1934, the follow-on “Second” New Deal—and the program’s more ambitious, transformative reforms—might never have come to pass. Indeed, one could argue that it was only the continued economic crisis that ensured the election of the massive Democratic majority (in the congressional midterms of 1934) required to pass the rest of FDR’s New Deal in 1935-36.

Just before the legislative midterm elections of November 1934, Roosevelt’s influential interior secretary, Harold Ickes, recognized that more transformative reform was needed to address the Depression. He noted in his diary that “[t]he country is much more radical than the Administration. … [Roosevelt] would have to move further to the left in order to hold the country.” True radicals, both left and right, as we shall see, were gaining popularity, and FDR—about to propose several of his transformative reforms in 1935—may well have shifted left in response to these fringe threats. From this perspective, Roosevelt did what he later did—ushering in a more leftist “Second” New Deal—in order not to destroy but to save American capitalism. These new measures, according to FDR’s son Elliott, were “designed to cut the ground from under the demagogues.” Roosevelt, himself, explained that he was working “to save our system, the capitalist system [from] ‘crackpot ideas.’ ” In another bold assertion, FDR told a Syracuse, N.Y., crowd:

The true conservative seeks to protect the system of private property and free enterprise by correcting such injustices and inequalities as arise from it. The most serious threat to our institutions comes from those who refuse to face the need for change. Liberalism becomes the protection for the far-sighted conservative. In the words of the great essayist [Lord Macaulay, not named by FDR], “Reform if you would preserve.” I am that kind of conservative because I am that kind of liberal. [Emphasis added.]

Still, despite such proclamations, this rather political interpretation of the New Deal’s motivation may overstate the case.

Roosevelt was, it must be admitted, at least partly driven by genuine empathy for the poor. As historian David M. Kennedy concluded, it was “solicitude for his country”—a distinct Roosevelt family value—“that lay at the core of his patrician temperament.” By this logic, FDR was a sympathetic, if paternalistic, person who was always both more and less than the “traitor to his class” that he was quickly dubbed. Indeed, as early as 1939, Raymond Moley observed that Roosevelt “is outraged by hunger and unemployment, as though they were personal affronts in a world he is certain he can make far better, totally other, than it has been.” So, if FDR’s policy was decidedly not communist subterfuge, it was still in many ways rather idealistic and transformative. By 1935, the president was waging a war of political persuasion meant to change the public’s mind about the role of federal government in poverty reduction and economic stabilization. Roosevelt recollected that the Constitution was established to “promote the general welfare” and that it was thus government’s “plain duty to provide for that security upon which welfare depends.” It was a battle, a war really, that FDR would ultimately win, at least until the conservative revival of the 1970s-80s.

Let us, then, surmise that Roosevelt had become a cautious idealist by 1935. In that year’s annual address to Congress, FDR declared that “social justice, no longer a distant ideal, has become a definite goal.” The common objective in his economic policies, then, seems to have been both the mitigation of the worst aspects of grinding poverty and the old progressive dream of stability—“wringing order out of chaos.” To provide this, Roosevelt needed to win over the hearts and minds of the majority of people to his own view that corporate business interests alone couldn’t be counted on to provide the stability and poverty mitigation needed in a modern industrial society. To this end, he declared that “[m]en may differ as to the particular form of government activity with respect to industry or business, but nearly all are agreed that private enterprise in times such as these cannot be left without assistance and without reasonable safeguards.” By his third year in office, Roosevelt had convinced an unforeseen majority of Americans of just that—and his policies of government investment and poverty alleviation would rule in Washington for at least the next 30 years.

From Reform to Disappointment: The ‘Second’ New Deal and Its Legacy

After securing record Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, Roosevelt unleashed his most ambitious and transformative legislation during the fateful 1935 congressional session. Ever more “alphabet soup”—acronym-laden—agencies and bills would be created and approved. These included even larger job creation programs, including the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). When the REA first put Americans to work, fewer than two out of 10 farms had electricity. A decade later, nine of 10 did. Even grander was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which put 8.5 million people to work during its eight-year lifespan, employing a variety of citizens, from construction workers to artists and authors, on various public projects. In the end, the WPA would build half a million miles of highways and almost 100,000 bridges. This was a federal investment in infrastructure that was unheard of and unimaginable just a few years earlier.

Still, there was controversy and scandal. Roosevelt was, whatever else he may have been, a savvy, consummate politician. Recognizing the old saw that “all politics is local,” the president used the WPA as a “gigantic federal patronage machine,” handing out jobs and projects to amenable (mostly Democratic) state and city-level politicians and administrators. Indeed, in one extreme case, all New Jersey WPA employees were required to “donate” 3 percent of their modest paychecks to the local Democratic Party. Nevertheless, in the short term at least, WPA projects reduced unemployment and provided millions the dignity of honest work.

Perhaps the most substantial, and long-lasting, piece of New Deal legislation was the Social Security Act. It included a program of lifelong old-age insurance, as well as institutional federal unemployment insurance. The insurance provisions for the elderly were motivated by both humanitarian considerations and practical economics. Much of America’s impoverished community was made up of septuagenarians, but so too was much of the workforce. Social Security benefits would both decrease poverty and “dispose of surplus workers” over the age of 65. Providing a marginal retirement fund for the elderly would, by this logic, open up more jobs for younger, able-bodied, unemployed men and women. Originally, Roosevelt and his New Dealers—as his loyal bureaucrats came to be called—wanted to include a national system of health care in the Social Security Act. This provision was doomed to fail and was quickly jettisoned, however, in the face of public, political and corporate obstacles. America, it seemed—unlike its European counterparts—was not yet ready for universal health care.

Even without the health care provisions, Social Security was a bold measure. Nonetheless, it was far from the socialistic, radical proposition that FDR’s enemies feared. Rather than finance the insurance through direct, progressive taxation, Roosevelt insisted that Social Security be based on “private insurance principles,” specifically that “the funds necessary … should be raised by contribution rather than an increase in general taxation.” Social Security was thus, in the words of historian David M. Kennedy, to be “not a civil right but a property right. That was the American way.” As such, rather than an income-redistribution program, this was to be a mandatory pension system financed by (regressive) taxes on the workers themselves. It remains so today.

When his more liberal advisers warned Roosevelt that Social Security would actually initially burden workers, decrease consumer spending (and thus hurt the overall economy) and fail to minimize income inequality, he replied simply that “I guess you’re right on the economics, but those taxes were never a product of economics. They are politics all the way through.” Progressive New Dealers also wanted Social Security insurance to pay the same amount to everyone, regardless of earned income, thus achieving some limited wealth redistribution. Again, Roosevelt, this time through his labor secretary, explained his opposition to such measures. “The easiest way would be to pay the same amount to everyone,” Frances Perkins concluded, “but that is contrary to the typical American attitude that a man who works hard, becomes highly skilled, and earns high wages ‘deserves’ more on retirement.” And so it would be. Here again, the Roosevelt administration based Social Security on the private insurance model, rather than the European income-redistribution model that prevailed (and prevails) in just about every other industrial nation.

Nevertheless, despite the moderation underlying most of his “Second” New Deal legislation, there is no doubt that FDR did tilt leftward in 1935-36. Yet even this was as much rhetoric as reality. In June 1935, Roosevelt pushed for tax reform, telling Congress that “[o]ur revenue laws have operated in many ways to the unfair advantage of the few, and they have done little to prevent an unjust concentration of wealth.” Thus, he asked for “very high taxes” on the largest of incomes and for “stiffer inheritance taxes.” FDR called his proposal a “wealth tax”; his opponents soon dubbed it a “soak-the-rich” plan. Still, in principle, tax reform polled well in Depression-era America.

Motivated by his legislative successes, Roosevelt took his smite-the-rich rhetoric out on the campaign trail when he ran for re-election in 1936. Whereas in his “First” New Deal, FDR had sought cartelization and cooperation with certain business interests, he now told a frenzied crowd in New York’s Madison Square Garden that his “old enemies … business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, war profiteering … organized money … are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.” At several campaign stops, Roosevelt railed against the supposed cabal of “economic royalists” standing in the way of his reforms. This combative language earned the president standing ovations lasting as long as 13 minutes!

What motivated this leftward turn, at least in rhetoric, was a desire to cow his socialist-leaning critics and build a wholly new political coalition. The president knew that many years of depression had bolstered the legitimacy of an extreme left wing in American political life, and that this faction—because of its potential to split the 1936 Democratic vote—was the real threat to his power and agenda. As FDR told a reporter during the tax debate in 1935, in order to combat “crackpot ideas,” “[i]t may be necessary to throw to the wolves the forty-six men who are reported to have incomes in excess of one million dollars a year.” As David M. Kennedy has concluded, the 1936 campaign rhetoric of “radicalism” was “more bluff than bludgeon.” Roosevelt had little to lose, at least politically, in demonizing the far right and the super-rich. What he sought to gain, however, was something far more transformative: a permanent coalition of workers, farmers, union men, minorities and liberal intellectuals. For these folks, populist bombast sold well. And it worked.

FDR won a record landslide victory in 1936 and appeared to have a stronger mandate than any president since James Monroe. His opponent, Alf Landon, had carried only two states in the Electoral College. Journalist William Allen White stated that Roosevelt “has been all but crowned by the people.” Still, if politics informed much of FDR’s radical tilt in 1935-36, there can be little doubt that he was also motivated, to some extent, by altruistic concern for the impoverished. In January 1937, in his second inaugural address, he laid out the core of his beliefs and agenda-setting philosophy for his next term. “The test of our progress,” he proclaimed, “is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

What’s more, at the dawn of 1937, the economy had finally begun to show signs of recovery. The Federal Reserve Board’s Index of Industrial Production had jumped from a score of 50 (out of 100) to 80 by late 1935. As of November 1936, the unemployment rolls had shrunk by nearly 4 million from the 1933 high. Then, as soon as recovery seemed imminent, the economy came crashing down again in mid-1937. Within weeks, a “second” depression kicked off; stock values plummeted by a third, and corporate profits dropped nearly 80 percent. By 1938, 2 million more workers had been laid off, bringing unemployment back up to an astounding 19 percent. Both conservative and radical leftist critics dubbed it the “Roosevelt Recession.” Many Americans would ask, both then and later, what had caused this second crash and the resultant economic downturn.

To some extent, the downturn was due to the simple, standard fluctuations of the business cycle in a still firmly entrenched capitalist economy. By this logic, because of the inherent ups and downs of the market, contraction was to be expected after four straight years of economic expansion under Roosevelt. Still, conservatives and laissez-faire economists blamed the recession on a lack of business confidence, arguing that FDR had demoralized corporations with his “radical” campaign rhetoric and relatively progressive tax policies. Though this may have been an appealing narrative for corporate leaders, it crumbles under closer examination.

Later Keynesian economists, and the most dedicated New Dealers in Roosevelt’s own administration, probably came closer to the mark. According to these thinkers, the reason for the 1937-38 recession was simple: The New Deal hadn’t gone far enough. The government, they claimed, had committed a few key errors in 1936-37. Roosevelt, still trapped in an older school of economic thinking, fretted over balancing budgets—the budget was actually in the black for the first nine months of 1937—and balked at more sorely needed deficit spending. His Federal Reserve, furthermore, worried about inflation, which can actually benefit a depressed economy, and contracted the money supply despite high levels of unemployment. Finally, the new regressive Social Security taxes took some $2 billion out of the national income without returning any benefits (which would not begin going out until 1940). The cure, according to the most zealous New Dealers, was simple: resume large-scale public spending. It might have worked, but by the middle of Roosevelt’s second term, large sections of the public and the resurgent (Southern) conservative wing of FDR’s own party had lost their stomach for more New Dealing. So it was that the depressed economy would sputter along until a new wave of deficit spending—ushered in by the military buildup for World War II—achieved a full recovery.

Despite all the experimentation inherent in the New Deal, and the energy with which FDR initially championed it, in the end Roosevelt proved to be a reluctant and moderate spender. In a certain sense the president wrought the worst of all economic worlds: insufficient government spending and fear of deficits on the one hand, and, on the other, beating the populist drum at a level high enough to unnerve corporate investment. By 1938, Roosevelt was much weakened as a political leader. The nation entered its ninth year of the Great Depression, and 10 million workers remained unemployed. For all that, at least democracy seemed safe in the United States. And Roosevelt remained convinced that some action toward poverty relief remained necessary to maintain that safety. Just a month after Adolf Hitler’s Germany gobbled up Austria, FDR declared, “Democracy has disappeared in several other great nations, not because the people … disliked democracy, but because they had grown tired of unemployment and insecurity, of seeing their children hungry … in the face of government confusion and government weakness.” If his New Deal had not brought recovery, at least it had not produced fascist or communist authoritarianism.

Radicals and Demagogues: Threats to the New Deal—Left and Right

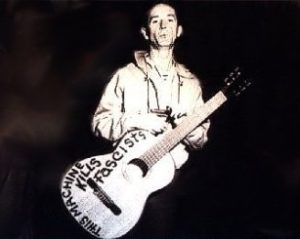

Was a big high wall there that tried to stop me A sign was painted said: Private Property, But on the back side it didn’t say nothing — [That side was made for you and me.]

One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple By the Relief Office I saw my people — As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering if [This land was made for you and me.]

—Politically radical verses from Woody Guthrie’s 1940 version of “This Land Is Your Land”

The New Deal, and the entire American democratic and capitalistic system, was always at risk from radicals and demagogues on the left and right ends of the political spectrum. Only through a juxtaposition of FDR and these more radical thinkers can we illustrate the truly moderate character of Roosevelt and his program. Furthermore, to ignore or marginalize more radical voices is to misunderstand the temper and anxieties of many Americans in the midst of the Great Depression. A crashed economy and skyrocketing unemployment are radicalizing triggers in and of themselves. There were, throughout the 1930s, many paths not taken as FDR carefully threaded the needle of restraint.

Some of the left-wing radicals were ideologically consistent socialists or communists, but many others were simply frustrated populists raging against the wealthy elites and their perceived collaborators. For example, in Iowa during April 1933, a mob of mask-wearing farmers abducted a judge in order to suspend foreclosure proceedings, threatened to lynch him and then left him beaten and naked in a ditch. The governor soon declared martial law in several Iowa counties. Then, in July 1934, longshoremen led a brief general strike that largely shut down San Francisco. Similar actions occurred in the textile mills of New England and the Carolinas in the same year. Such outbursts of violence and militant strikes were fairly common and convinced Roosevelt of the urgency for reform actions.

Leftist intellectuals, artists and avowed communists and socialists also menaced Roosevelt from the left. The League for Independent Political Action, founded in 1929 by a University of Chicago economist, declared that “[c]apitalism must be destroyed” and that “no such compromise [the New Deal] with a decaying system is possible.” A hero of the league, Floyd Olson, said as late as 1935 that “American capitalism cannot be reformed” and a “third party must arise and preach the gospel of government collective ownership of the means of production and distribution.”

Such communalist ideals also infused the work of socialist-influenced artists. For example, the famed novelist John Steinbeck wrote in his 1939 award-winning book, “The Grapes of Wrath,” which would be made into a popular 1940 film:

And the great owners, who must lose their land in an upheaval … with eyes to read history and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away. And that companion fact: when a majority of the people are hungry and cold they will take by force what they need.

Furthermore, the acclaimed African-American poet Langston Hughes was one of many artists to sign a manifesto declaring that “as responsible intellectual workers we have aligned ourselves with the frankly revolutionary Communist Party.” Indeed, communists and socialists, as well as their sympathizers, were prominent in parts of the labor movement as well as in Hollywood.

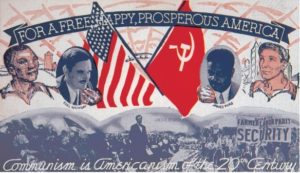

Disgruntled members of the old Eugene Debs-led American Socialist Party had formed the Communist Party USA in 1919, and by 1932, as noted in the caption above, the party ran a black man for vice president of the United States. The Communists received over 100,000 votes in ’32, an all-time electoral high for the party. Official membership in the party rose by a factor of 30 from 1930 to 1935. Roosevelt recognized this challenge from his far left and ramped up his economically populist and redistributionist rhetoric for the 1936 presidential campaign.

Additionally, popular demagogic figures arose during this period and challenged Roosevelt from the far left and right. Louisiana’s popular Sen. Huey Long created the Share Our Wealth Society in January 1934, with promises to radically redistribute income and make “every man a king.” Another famous activist, the progressive novelist Upton Sinclair, won nearly a million votes for California’s governorship in running on a utopian “production-for-use communitarian platform.” Finally, the eccentric, anti-Semitic “radio priest” Charles Coughlin combined both left- and right-wing policies—just as the German Nazis had—and formed the National Union for Social Justice. This organization had a platform promoting inflation and railing against international Jewry. The power and popularity of these men, as well as their influence on Roosevelt, should not be underestimated.

Long, known as “the Kingfish,” was probably Roosevelt’s most popular competitor during the early New Deal. He was a shrewd operator and a powerful orator. He attacked Wall Street and corporate barons, utilizing the well-worn language of class resentment and William Jennings Bryan-style populism. Long made no secret of his fanaticism, declaring in 1935 that he “wished there were a few million radicals [in the United States].” His zealous dream of economic leveling was apparent even before the Depression, when he won the Louisiana governorship on the slogan “Every man a king, but no one wears a crown.” As a senator, Long carried his contempt for the elite political establishment into D.C. with the swagger of what some called a “hillbilly hero.” Though Long was initially a supporter of the New Deal, Roosevelt called him “one of the two most dangerous men in the country.” (The other, FDR said, was Gen. Douglas MacArthur.)

Roosevelt’s fears and instincts were borne out. By 1934, Long decided that the New Deal had not gone far enough, and his Share Our Wealth Society called for the confiscation of large fortunes, a steep income tax on the rich and the redistribution of $5,000 to each and every American family. Economists recognized that the dollars didn’t add up; as one put it, “confiscating all fortunes larger than a million dollars would only produce … a mere $400” per family. Still, neither Long nor and his faithful supporters were daunted for a moment. The Kingfish would announce over the radio that his listeners should “[l]et no one tell you that it is difficult to redistribute the wealth of this land. It is simple.” By 1935, Long’s organization claimed 5 million members. Then, in a direct threat to FDR, Long told reporters “that Franklin Roosevelt will not be the next president of the United States. … Huey Long will be.” In response to these boasts, a worried pro-Roosevelt Democratic senator warned that Long “is brilliant and dangerous. … The depression has increased radicalism in this country … the President is the only hope of the conservatives and the liberals; if his program is restricted, the answer may be Huey Long.”

Long wasn’t the only radical challenger to Rooseveltism. “Radio priest” Charles Coughlin, a naturalized American but Canadian-born, could not directly challenge FDR by running for the presidency himself, but the movement he unleashed pecked at the New Deal order from both the left and right. The Coughlin constituency included largely lower-middle-class ethnics, often only one generation removed from Southern and Eastern Europe, who had found some level of prosperity before the outbreak of the Depression. These dispirited workers were attracted not to Coughlin’s religion but to his unique brand of populist politics. Coughlinites denounced international bankers and the gold standard while demanding inflation to mitigate debts. That was the leftist component of the muddled ideology. On the other hand, his supporters also fiercely attacked communism and campaigned against Wall Street, whose machinations they attributed to supposedly sinister Jewish business executives. Coughlin certainly seemed an imminent threat to the Democrats, especially after he declared that the old political parties are “all but dead” and founded the National Union for Social Justice, which boasted some 8 million members at its peak. Indeed, by 1934, Coughlin received more mail than any other American, including the president.

Reviewing this evidence, many historians have concluded that Long’s threats pressured FDR into his more activist New Deal proposals in 1935. While that may be an oversimplification, Roosevelt was, no doubt, concerned about his left and right flanks. As the president told a journalist in early 1935, “I am fighting Communism, Huey Longism, and Coughlinism.” He was working, as he often explained, to “save our system, the capitalist system” from “crackpot ideas.” Long would soon be assassinated and Coughlin’s following diminished, but Roosevelt no doubt had these men and their followers in mind when he spoke of “crackpots” and their fanciful ideas in the mid-1930s.

The Rise, and Division, of American Labor

The American labor movement never had the power and prestige of its European counterparts. The U.S. had no labor party, to speak of, and socialism never gained much of a foothold in pre-Depression America. This outcome was, it seems, a result of the nation’s peculiar ethnic diversity and nativism and its legacy of racial slavery; however, it was also due to massive violent crackdowns unleashed by the corporate-friendly American state throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In a certain sense, it was in fact the New Deal that promoted the “golden age” of American labor. Still, seen from another angle, neither the New Deal nor Roosevelt himself was a steadfast friend of labor, and, indeed, the labor movement only fractured further and alienated many Americans during the era. Viewed through this lens, the period ended with the co-opting of labor by the centrist Democratic Party. The movement’s power and potential never to come to fruition.

Nevertheless, the early successes of labor unions during the Roosevelt administration must be noted. Only 6 percent of workers belonged to unions in 1929, but by 1939 that number had risen to some 33 percent. No doubt, some New Deal legislation seemed to catalyze this growth. After the passing of the NIRA—which include a modest right to unionize—the president of the United Mine Workers (UMW), John L. Lewis, took to declaring in radio addresses and speeches that the “president wants you to join a union.” Moreover, the 1935 Wagner Act, which officially guaranteed the workers’ right to organize and required employers to bargain with union representatives, seemed to bolster Lewis’ agenda. With such soaring rhetoric, Lewis rose to the fore of the entire American labor movement, even if his declaration about what the president wanted wasn’t wholly factual. In fact, we now know that FDR was lukewarm toward labor, feared its potential radicalism and preferred government regulation and social welfare to union-led collective bargaining. The Wagner Act and the NIRA were actually compromise measures forced on the administration by grassroots activism and the president’s urban ethnic constituencies.

No matter, by 1934-35 labor felt it had the wind in its sails, partly because of a popular president. In 1934 unions staged 2,000 strikes across almost every industry in every region of the country. Some led to violence and public sympathy for the strikers. Then, in the famous and successful 1936-37 “sit-down” strikes, United Auto Workers (UAW) members “occupied” several General Motors plants in Flint, Mich., and refused to move until their demands were met. According to historian David M. Kennedy, this was nothing less than “the forcible seizure by workers of the means of production.” And, when the Michigan governor refused to call in troops to enforce the court injunction against the strikers, the UAW won most of its demands: recognition of union bargaining rights, a shorter workweek and a minimum wage. The role of government in all this was actually minimal. Though FDR worked behind the scenes to urge GM to settle, the main contribution of government was, quite simply, staying out of the way. This represented a major turnaround from the violent military and police interventions of earlier decades.

This was the high tide of labor success in the Depression era. The victorious sit-downers emerged from the GM plants full of buoyant energy and waving American flags. They seemed, for once, to have overcome the racial and ethnic divisions that had plagued organized labor in the past. One worker declared, “Once in the Ford plant they called me ‘dumb Polack,’ but now with the UAW they call me brother.” Though stirring, this sentiment was, for the most part, just wishful thinking.

The American labor movement had actually fractured once again. The older American Federation of Labor (AFL), populated mostly by old-stock Anglos, threw all its energy behind skilled tradesmen. Factory workers and unskilled laborers (who were usually newer Italian and Slavic immigrants) on assembly lines were often ignored by AFL leaders. John Lewis of the UMW recognized this fault early on and by November 1935 formed the more radical Committee for Industrial Organization (later known as the Congress of Industrial Organizations). The CIO, in theory, called for ethnic and racial equality in union membership, but this additional hint of radicalism often served to alienate the public, especially in the conservative and labor-unfriendly South.

What’s more, despite the victories in the sit-down strikes, the workers themselves lost much public sympathy. Many middle- and upper-class Americans feared the radicalism and effectiveness of the spreading sit-down strikes and quickly turned on organized labor. This was especially the case after various union branches began calling sudden “wildcat” sit-down strikes across the country, copying the successful Flint model. Rumors of communist infiltration—often exaggerated by corporate interests—further hurt the public image of the CIO unions, including the United Mine Workers and the United Auto Workers. At this point, Congress jumped in, with Rep. Martin Dies of Texas opening the first hearings of the new House Committee for the Investigation of Un-American Activities (HUAC) by calling sympathetic AFL spokesmen to Washington. These opponents of the CIO played their appointed role and attacked the new movement as “a seminary of Communist sedition.”

Furthermore, major corporations fought back with a vigor rarely seen before or since. Businesses contributed to anti-labor advertising campaigns and also resorted to subterfuge and force to break the unions. Ford Motor Co. had long suppressed unionism and even built up a paramilitary force of some 3,000 armed men to stalk and threaten “disloyal” employees. GM, for its part, invested $1 million to “field a force of wire tappers and [union] infiltrators” to combat the UAW. Radical labor’s Waterloo came during a steel strike over Memorial Day weekend of 1937. When a UAW marcher threw a stick toward approaching police, pistol shots rang out and the law enforcement agents essentially rioted. When it was over, 10 strikers were dead, seven shot in the back. Thirty others, including a woman and three children, were wounded by gunfire, and nine of them were permanently disabled as a result.

At this point government power intervened in the more traditional way. Pennsylvania’s governor imposed martial law in the wake of the steel strike, and Ohio’s governor did the same in Youngstown after two shooting deaths of steelworkers there. All told, the summer of 1937 saw 18 workers killed. Still, public sympathy had by then shifted from labor and moved to the side of business and the police. The radical potential of the sit-down strikes, when combined with an effective corporate propaganda campaign, disquieted a majority of Americans. President Roosevelt was now in a tough spot. He couldn’t side with labor without being seen to sanction the increasingly unpopular sit-downers, but he couldn’t attack labor without alienating some of his most loyal voters. As was typical, Roosevelt chose the middle path. He declared a “plague on both your houses [business and the union],” and just like that, as historian Irving Bernstein concluded, “A brief and not very beautiful friendship had come to an end.”

Despite such disappointments, organized labor did not abandon Roosevelt as he had abandoned it. On the contrary, union workers had, by the end of the 1930s, become reliable Democrats. This destroyed, once and for all, the old labor dream of a separate workers’ party, such as existed in much of Europe. Unions abjured calls for the fall of capitalism and became mainstream players in the two-party political system. In this process, as David M. Kennedy noted, “they wrote the epitaph for American socialism.”

‘Affirmative Action,’ but Only for Whites

“The Negro was born in depression. … It only became official when it hit the white man.” —Clifford Burke as quoted by Studs Terkel in an oral history of the Great Depression

At the height of the New Deal, according to the black scholar and historian W.E.B. Du Bois, some 75 percent of African-Americans still were denied the right to vote. Since at least 1877, blacks could count on neither major political party to reliably champion their rights. Nonetheless, it was, undoubtedly, during the Great Depression that a supermajority of African-Americans moved toward the Democrats. That this should be so is somewhat odd. The Democratic Party, we must remember, was the preferred party not only of Civil War-era Confederates but of postwar segregationists and white supremacists. Indeed, by the 1930s the Democrats boasted a single-party system—in which they were unchallenged by Republicans—across the Old South. Still, there was something about Franklin Roosevelt, a scion of a Northern patrician family, and his New Deal that appealed to America’s largely impoverished black population. Black Americans saw hope in the man and his policies. Tragically, their faith would prove misplaced and they would soon find themselves left out of the New Deal’s largesse in a carefully orchestrated system that achieved nothing less than white “affirmative action.”

The main culprits in this epic sellout were powerful Southern Democrats along with FDR himself, who proved all too willing to compromise with these white supremacists—a decision that the president saw as politically necessary. The Southern wing of the Democratic Party had long been dominant. This requires some explanation and analysis. Given the peculiar American system of state-based senatorial representation, the 17 states that mandated racial segregation had a combined 34 seats in the Senate. Almost all were Democrats, as single-party rule was the norm in the South, blacks (who largely favored the GOP, the party of Lincoln) were disenfranchised and the Republicans rarely even ran an opposing candidate. Thus, these senators made up the majority of Democrats in the Senate and had undue influence on the party platform and policies. Furthermore, these senators—along with Southerners in the House—usually had the most seniority in Congress and thus chaired the key committees, controlling which bills made it to the floor for debate and a vote. Finally, because of the low franchise among African-Americans and with blacks counted for representation purposes although they were blocked from voting, each white Southerner in Congress had far more statistical sway in Washington than his Northern counterpart. Throughout the New Deal era, these dominant Southerners would use their power for one primary purpose: to maintain their apartheid system of white supremacy.

The new attraction of Northern blacks to the Democratic Party and the apparent sympathy of Southern blacks for New Deal socioeconomic reforms were seen very differently by African-American leaders and Southern white party leaders. Whereas one black preacher in the South hopefully told his flock to “[l]et Jesus lead you and Roosevelt feed you,” the attraction of African-Americans to Roosevelt and his New Deal was seen as a threat by many whites. As one Georgia relief agent concluded, “Any nigger who gets over $8 a week is a spoiled nigger, that’s all. … The Negroes regard the President as the Messiah, and they think that … they’ll all be getting $12 a week for the rest of their lives.” Here we see an early manifestation of the belief among white bigots that blacks were lazy and reliant on government welfare by their very nature.

From a neutral perspective, black enthusiasm for the New Deal was wholly understandable. As was, and is, always the case in American history, depressions and recessions tend to have disproportionate effects on the black community. In 1932, for example, black unemployment reached 50 percent, double the national rate. Often the last hired, blacks were usually the first fired. Despite Roosevelt’s later sellout of American blacks, there were reasons for hope upon his first election. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt would remain a vocal proponent of black civil rights throughout her husband’s tenure, even if FDR often failed to follow her lead. Still, in 1933 the president did consult an informal group of advisers known as his “black cabinet” and appointed the first ever black federal judge.

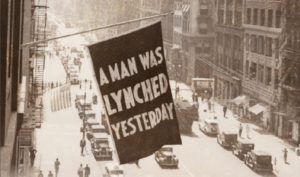

Nonetheless, the Depression only increased Southern anxiety and raised the rates of terror attacks in the region. Lynchings tripled in 1932-33, with 23 such killings occurring in a single span of 12 months. This shocking statistic led the Congress to propose, once again, federal anti-lynching legislation. Northern Democrats and African-Americans hoped, in vain, that FDR would throw his weight behind the bill. He would not, and the bill failed again in the face of Southern intransigence and a ubiquitous Senate filibuster. During the marathon six-week filibuster, Louisiana Sen. Allen J. Ellender made clear the stance of his fellow Southerners, proudly declaring, “I believe in white supremacy, and as long as I am in the Senate I expect to fight for white supremacy.” For his part, Roosevelt felt he had no choice but to abandon the bill to its inevitable fate. As he told the NAACP’s Walter White, “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they [Southern Democrats] will block every bill I ask Congress to pass to keep America from collapsing. … I just can’t take that risk.” From the president’s perspective, civil rights legislation would, once again, have to wait.

By and large, though, the real crime of the New Deal was the way it excluded blacks from the structural social safety net and relief budgets. It was the Southern Democrats who ensured this by insisting on—and gaining FDR’s acceptance of—local control of federal relief and employment programs. Southern political leaders insisted this be the case as the price for their legislative support. For example, when South Carolina Sen. Ellison “Cotton Ed” Smith learned that New Deal programs might provide cash relief to black tenant farmers, he stormed into a government administrator’s office and exclaimed, “Young fella, you can’t do this to my niggers, paying checks to them. They don’t know what to do with the money. The money should come to me. I’ll take care of them. They’re mine.” Unsurprisingly, local welfare administrators in the South segregated such programs or rejected them outright on the basis of race.

Then, when Congress passed the Social Security Act—with its substantial old-age insurance and unemployment relief components—the Southern Democrats again twisted the legislation to exclude blacks. Though the bill would have no specific racial language, the Southerners insisted on, and won, a provision to exclude farm laborers and domestic servants from Social Security coverage. Thus, at a stroke, 9.4 million of the most needy workers—a disproportionate number of them black and brown—were denied these benefits. The results were tragic and far-reaching. Whereas white workers benefited from the “affirmative action” of a social safety net and old-age insurance, blacks fell ever further behind. By the 21st century, white household wealth was on average nine times that of black families.

Roosevelt and the Democratic Party were directly complicit and caught up in this corrupt system of racial exclusion. It’s important to understand that the white supremacists in the party were not conservatives in the contemporary sense of the word. The South was largely a dirt-poor region. It’s Democratic representatives liked the New Deal and its social welfare programs—so long as the programs didn’t upset the region’s structural racial caste system. Consider the irony and staggering juxtaposition of FDR and perhaps the most virulently racist in the Congress, Sen. Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi. Bilbo proudly declared in 1938 that “[the U.S.] is strictly a white man’s country… one drop of Negro blood placed in the veins of the purest Caucasian destroys the genius of his mind.” Despite this shocking assertion, Bilbo would proclaim, two years later, “[I am] 100 percent for Roosevelt … and the New Deal.” And when this deplorable man was re-elected by a landslide in 1940, FDR himself sent a letter to Bilbo containing this sentence: “I was so delighted to learn of your splendid victory … assuring … a real friend to liberal government.”

Perhaps the paradox and contradictions appear staggering. And indeed they were. Such were the fissures in the inherently unstable “big tent” of the 1930s Democratic coalition. Roosevelt felt he had to work with the monsters in the South to “save” and “transform” America. This led him into some disreputable bargains that haunt his reputation. So it was, then, that “liberal,” yet racist, Southern legislators crafted the New Deal into what it ultimately became, a system that historian Ira Katznelson has labeled a combination of Sweden (social welfare) and South Africa (apartheid). We live with the results of that Faustian bargain even today.

Blacks were not the only citizens left out of the New Deal. Women were also often denied the benefits of its legislation. For one thing, they were overrepresented in the workforce as domestic servants and waitresses, both excluded from benefits. And, in order to restore male dignity, many states passed laws outlawing the hiring of married women. Local relief agencies were reluctant to authorize aid checks to jobless women. Indeed, the mass firing of women was seen by some commentators as a formula to end the Depression. As Norman Cousins of The Saturday Evening Post wrote, the national emergency could be ended simply by giving pink slips to 10 million employed women and then giving their jobs to men. “Presto!” he wrote, “No unemployment, no relief roles. No Depression.”

Despite the supposed “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment, blacks, Mexican-Americans and many women were denied the full economic citizenship provided to their white and male counterparts. And blacks could not use the ballot box to raise any significant dissent because only 4 percent were registered to vote. As such, we may conclude that for at least 30 years—until the legislative advances of the 1960s—one couldn’t truly consider the U.S. a genuine democracy. That would be the work of a future generation.

A Dangerous Man?: FDR the ‘Dictator’

Adolf Hitler took office as Germany’s chancellor just a few months before Roosevelt’s first inauguration, in March 1933. This is a more than interesting coincidence. Liberal democracy was dying throughout the world in the 1930s. Many citizens, and scholars even, had begun to doubt the ability of elected legislatures to solve the big problems of the day, notably worldwide economic depression. One-party totalitarian systems—fascism in Italy, Spain and Germany and communism in the Soviet Union—seemed the way of the future. Given this fact, and the economic devastation the Depression wrought in the United States, it is surprising that FDR did not assume the powers of a dictator at some point during his years in office.

Roosevelt did flirt with rule by executive fiat and was seen by many opponents as something nearing a tyrant. We must ask, then, whether FDR was, indeed, a dangerous man and examine the contours—and limits—of his personal power. Many commentators, even liberals and old-time progressives, in fact urged Roosevelt to assume singular power. Even before his inauguration, America’s most famous editorialist, Walter Lippmann, wrote to Roosevelt, “You may have no alternative but to assume dictatorial powers [to end the Depression].” And, in fact, Roosevelt threatened as much in his first inaugural address. Many of his supporters loved it! Today, we forget that the biggest applause line in this famous speech wasn’t “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” Rather, the crowd roared most loudly when FDR declared that if the legislature failed to act according to his views, “I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” This remarkable, if disturbing, statement earned the new president cheers, but his limited moves in that direction would meet with major opposition.

Roosevelt ran into the most trouble and disapproval in response to his so-called court-packing scheme. Fearing that the rather conservative, mostly Republican-appointed Supreme Court would strike down most of his New Deal legislation as unconstitutional (it had already overturned 12 such measures in the preceding months), Roosevelt proposed legislation that would allow him to appoint an additional justice for each justice over the age of 70 who refused to retire. Though a staggering reorganization of the judicial branch and an infringement on its independence, FDR felt the proposal was justifiable. His plan would weaken the power of the most conservative justices on the court—“the Four Horsemen”—all of whom were 70 or older. FDR saw this as a necessity to “save” the economy. His attorney general, after all, had warned the president that “they [the court] mean to destroy us. … We have to find a way to get rid of the present membership of the Supreme Court.” And, from Roosevelt’s perspective, these septuagenarian conservative justices were out of touch with the needs of a new industrial economy griped by depression.

However, in this case Roosevelt’s political motivations were all too clear. A massive public outcry ensued. The columnist Dorothy Thompson wrote, “If the American people accept this last audacity … without letting out a yell to high heaven, they have ceased to be jealous of their liberties and are ripe for ruin.” The president’s Court Reform Bill opened him to renewed charges of dictatorship, and not just from his traditional conservative opponents. A plurality of Democratic congressmen abandoned him, and a Gallup survey of the public showed that fully 55 percent of the population opposed the “court-packing.” The bill never passed, and Roosevelt’s popularity was permanently damaged.

Nonetheless, though the president had lost the battle, he may have won a (Pyrrhic) victory in the war. Soon after Roosevelt’s announcement of the plan, Justice Owen Roberts switched sides and the court began approving each piece of key New Deal legislation. What one commentator called “the greatest constitutional somersault in history” has since been labeled the “switch in time that saved the nine [-justice court].” Though FDR never managed to expand the court, he had, he observed, “obtained 98% of all the objectives intended by the Court plan.” True enough, but the court-packing scheme had exposed the deep fissures in the president’s own party. Southern Democrats abandoned him and began to fear that if the executive branch could request and gather such federal power on this issue, it might later delve into the South’s own “business” of racial segregation. For the rest of his time in office, Roosevelt would face taunts about his “dictatorial” temperament from these Southerners and many others. For example, in the midst of the crisis, the famed H.L. Mencken published a satirical essay on the American Constitution that began: “All government power of whatever sort shall be vested in a President of the United States.”

Ultimately, however, despite his flirtations with strongman rule and sometime bending of the rules, Roosevelt never governed by full executive fiat. He, unlike Mussolini or Stalin, accepted the constitutional primacy of legislatures and accepted far less than he proposed through compromise with Congress. In the final analysis, FDR may have been dangerous, but he was not a dictator. His loyalty to the Constitution and his fealty to executive limitations may have been just the thing that saved America’s admittedly flawed democratic system. It is hard to know if another man would have demonstrated such humility and restraint when times got tough. Those qualities must remain a significant part of Roosevelt’s legacy.

Backlash: Sowing the Seeds of a New Conservative Political Movement

For all that, Roosevelt still alienated large portions of the American electorate and the established power structure. His policies and persona earned him the undying ire of a new conservative movement that formed in response, and in opposition, to all things Roosevelt. Today, the resurgence of conservatism and its takeover of the Republican Party are traditionally dated back to Richard Nixon (1968) or Ronald Reagan (1980), but in reality its seeds had been sown by 1935. That nascent movement of the 1930s and its anti-FDR bona fides remain a major part of American political life to this day.

By 1934, organized corporate interests felt threatened enough by the New Deal that they worked with conservatives within the president’s own Democratic Party to form the American Liberty League, an organization whose birth marked the start of organized opposition to Roosevelt’s policies. Then, in 1935, the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, after hearing of FDR’s “wealth tax,” branded the president’s proposal “Communism” and took to referring to him as “Stalin Delano Roosevelt.” This, despite the fact that the top tax rate of 79 percent on incomes over $5 million covered precisely one individual: John D. Rockefeller. Then, in response to Roosevelt’s 1936 campaign attacks on “economic royalists,” some employers slipped propaganda into workers’ paychecks falsely claiming that the Social Security Act would “require all participants to wear stainless-steel identification dog-tags” and that there was “no guarantee” that workers would ever see a return on their payroll-tax deductions.

Worse still for Roosevelt, at the end of the 1937 special congressional session—in which not a single one of the president’s bills had passed—a large, bipartisan group of Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans released a 10-point “Conservative Manifesto.” It attacked union strikers, demanded decreased taxes, defended states’ rights and criticized growing federal power. Historian David M. Kennedy has labeled this document as the “founding charter for modern American conservatism.” Then, in the 1938 elections, the Republican Party rebounded, winning more seats than at any other time since 1928. This was a knockout blow to the New Deal, and Roosevelt would pass hardly any social welfare legislation for the remainder of his presidency.

In Congress, the new HUAC committee hinted that FDR’s program was “communistic,” and the panel cultivated ties with right-wing groups and worked closely with FBI head J. Edgar Hoover. Committee members and their public supporters began to claim that the New Deal was a communist conspiracy spearheaded by “new” foreigners who had gotten into the country despite the restrictions of the 1924 Immigration Bill. Some referred to Roosevelt’s policies as a “Jew Deal.” HUAC Chairman Martin Dies promised to wage “relentless war without quarter and without cessation” on 3.5 million—mostly Jewish, Italian and Slavic—immigrants that he (dubiously) claimed had entered the country illegally. He even blamed the Depression on these immigrant groups, stating, “If we had refused admission to the 16,500,000 foreign born who are living in this country today, we would have no unemployment problem.” Tragically, when German Jews sought refuge in the U.S. from Nazi rule throughout the later 1930s, it was Dies and his fellow “new” conservatives who mobilized the congressional opposition that stood in their way and relegated many of them to concentration camps and ovens.

That aside, whether for better or worse, Roosevelt’s experimental, innovative federal welfare legislation, along with the fact that he was loved among immigrant workers, helped rally to the standard of conservatism a new swath of disgruntled Americans. And not all of them were rich, corporate businessmen. Just as Roosevelt had delivered a new, and for a time dominant, coalition of minorities, urban ethnics, impoverished farmers and liberal intellectuals, his conservative opponents began forming their own nascent consortium. This grouping would include Southern racists, Anglo nativists, business interests, states’ righters, opponents of welfare “excesses” and a stable upper-middle-class grown ever more fearful of the strength of unions and minorities. That coalition would stem the liberal tide by 1968 and decisively seize power in 1980. In our own day it rules the U.S. Senate and the office of the presidency.

* * *

What, then, can we conclude about the New Deal and its legacy? Let us start with what it did not do. Roosevelt’s flurry of legislation (1933-37) did not end the Depression. It did not meaningfully redistribute the national wealth (America’s income profile was, in 1940, much the same as it had been in 1930). Nor did it challenge the system of capitalism or the tenet of private ownership. The New Deal was never as “socialistic” as its enemies had claimed. What it did do, importantly, was put in place institutional structures that provided security to large numbers of Americans. The New Deal regulated banking, helping prevent a major economic crash until 2008, after, it must be noted, Glass-Steagall restrictions had been overturned. It stopped an avalanche of bank and mortgage defaults through new systems of federal controls, many still in existence. The New Deal must be said to have put in place a security apparatus for banking and homeownership that facilitated the postwar suburban housing boom of the 1950s-60s. Most decisively, the New Deal increased the power of the federal government and put to rest (at least temporarily) the notion that the “market” and the goodwill of the private sector were sufficient to sustain a secure economy for all. Thenceforward, the U.S. government would play a decisive role in market regulation, poverty relief and labor practices.

Roosevelt may have been too optimistic when he promised that the New Deal would “make a country in which no one is left out,” but the program did take steps in the direction of economic security (for most, at least). If the New Deal didn’t substantially challenge capitalism, it did upend the role of the federal government in the constitutionally mandated “protection of the general welfare.” And, notably, it did so without shredding the Constitution. Roosevelt eschewed radicalism, and, as David Kennedy concluded, “prevented a naked confrontation between orthodoxy and revolution.” This was no small matter.

As the historian Jill Lepore has noted, “FDR’s ascension marked the rise of modern liberalism.” Indeed, the Democratic Party, strengthened by the new “Roosevelt coalition”—of blue-collar workers, union men, Southern farmers, racial minorities, progressive intellectuals and women—would dominate American politics for nearly three decades after FDR’s death in 1945. Still, the new, powerful coalition was always inherently unstable and contained within itself the sources of its own destruction. Southerners and Northern white working-class ethnics were always less than comfortable in an alliance with poor blacks, who were seen as a threat both to the prevailing racial order and the job/wage prospects of white workers. By the mid-1960s, at the latest, these inconvenient undercurrents of tension would explode and the coalition would break over the emotional issues of black civil rights and government-sponsored social welfare programs. The result, we now know, was an empowered conservative movement and Republican Party that has, arguably, commanded American politics ever since. The seeds of all this were in the New Deal and the Roosevelt coalition from the very start.

Whether one reveres Roosevelt and his New Deal or perceives him and his program as the forebears of wasteful spending and an overpowering federal welfare state, on one point perhaps all can agree. What appears most remarkable about FDR, his Depression-era leadership and his New Deal is this: For whatever reason—be it the president’s brilliance or sheer luck—the United States, unlike many other Western nations, avoided the radical and authoritarian turns toward communism or fascism that paved the road to another world war. Early in Roosevelt’s tenure, the soon-to-be-famous British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote the following to the new president:

You have made yourself the trustee for those in every country who seek to mend the evils of our condition by reasoned experiment within the framework of the existing social system. If you fail, rational change will be gravely prejudiced throughout the world, leaving orthodoxy and revolution to fight it out. But if you succeed, new and bolder methods will be tried everywhere, and we may date the first chapter of a new economic era from your succession to office.

At this, at least, Roosevelt would succeed, in promoting rational change and avoiding excessive radicalism or revolution. FDR threaded the needle between the overpowering currents on the rise elsewhere in the industrial world.

What is less clear is whether Roosevelt’s middle path was ultimately best. After all, his relative conservatism on matters of labor, race and deficit spending (he regularly insisted, contrary to common memory, on balanced budgets!) sounded the death knell of socialism in America, ensuring that the United States, alone among highly developed Western nations, would have neither universal health care nor a powerful labor party. By co-opting the poor, the farmers, the urban workers, the intellectuals and minorities within his new Democratic coalition, he essentially bolstered the American two-party system and slammed the door on any “third-way” policies. FDR was, in the end, no “traitor to his class.” On the contrary, he saved the wealthy—both the newly rich and his own patrician blue bloods—from what might very well have been the collapse of the capitalist system itself. It was a fact that many of his enemies among the “economic royalists” were too shortsighted to realize.

Through his perhaps unique combination of genuine empathy, paternalist practicality and political savvy, FDR escaped revolution from either the left or the right. Still, in pursuing a pragmatic path, he left much social justice struggle to future generations and left the conservative movement very much intact. It would fall to others to strive toward racial equality, more far-reaching poverty reduction programs and a truly egalitarian wealth redistribution. His Democratic successors would try, falter, compromise and ultimately fail in this later mission, ceding much political ground to a newly empowered conservative Republican Party. By the 21st century, the Democrats, in the interest of winning elections, would tilt so far to the right as to be nearly indistinguishable from the rising Republicans. Democrats could still emerge victorious from time to time, but by the end of the second decade of the new millennium, income inequality would again reach levels unseen since the start of Roosevelt’s first term.

Had FDR not gone far enough? Did his middle path doom the New Deal? Today, with wealth disparity again reaching record levels, racism and nativism back on the rise, organized labor on life support, and globalization castrating American manufacturing, it would seem—at least to progressives—that both questions must be answered in the affirmative. Nevertheless, given the time, the stalwart American tradition of individualism and the power of the conservative opposition, expecting more from Roosevelt may constitute wishful thinking of the highest order. Seen in this light, Franklin Delano Roosevelt—the man, the dream and his policies—charted both the possibilities and limitations of progressivism in America. As for the United States, a conservative country it was, and perhaps it shall remain.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle, “Ruling America: A History of Wealth and Power in a Democracy” (2005). • Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle, editors, “The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930-1980” (1989). • Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001). • Ira Katznelson, “When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America” (2005). • Ira Katznelson, “Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time” (2013). • David M. Kennedy, “Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1946” (1999). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.