What Really Stands in the Way of Closing Gitmo

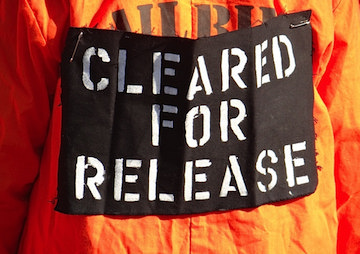

With nine months left until a new president is inaugurated, it has to be asked: Can the U.S.’ signature war-on-terror prison at Cuba's Guantanamo Bay ever be closed? An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

And yet for anyone hoping to see that prison closed in our lifetimes, sooner or later the idea of transferring those formally charged with terrorism to the federal courts will have to be revived. The place of choice, were this to happen, should probably be a courthouse relatively close to the White House: the Eastern District Court of Virginia (EDVA). It has, since 9/11, overseen a variety of high-profile terror cases, including those of Zacarias Moussaoui, John Walker Lindh, and Abu Ali.

It is also an inside-the-Beltway courthouse; its judges and prosecutors are familiar with using intelligence-related classified information. It is near the Department of Justice and can call on the expertise of officials at the FBI, CIA, and elsewhere who have been working on these cases for years. Finally, it has earned a reputation as the “rocket docket,” a fast-paced venue that tries such cases with speed — and given how long these trials have been postponed, speed is an important consideration.

Closing Gitmo?

There are a variety of ways that the EDVA could receive cases from the military commissions, ranging from a presidential act in defiance of a Congressional ban on transferring any Gitmo prisoners to the U.S. to actual congressional authorization. There is, however, one man who could make all of this far more likely and that’s Brigadier General Mark Martins, the chief prosecutor of the Office of Military Commissions since 2011. With soldierly loyalty, a sharp legal mind, and a charismatic public demeanor, Martins has for six long years defended the ability of the Guantánamo commissions to succeed as constitutionally and legally valid courts with built-in protections and procedures that approach those of federal criminal courts. He has the power to declare the commissions no longer viable, leaving the administration with little choice but to close them. Were he to do so, it would be a game-changer.

A former adviser to General David Petraeus in Iraq and Afghanistan and co-chair of the task force that revived the commissions after Obama came into office, he has suffered one setback after another. In these years, he has been blindsided by the CIA’s attempts to spy on the commission’s Gitmo courtroom, as well as on the rooms where attorneys meet the defendants they represent. He’s been stopped in his tracks by federal courts that declared the main charges against the detainees he was trying “unlawful”; embarrassed by the mysterious transfer of defense counsel materials to the prosecution’s computers; and humiliated, month after month, by the failure to deliver on the promise he made that the commission’s procedures in their “fundamental guarantees of a fair and just trial” would be “comparable to trials in federal courts.” Those procedures have instead proven to be a farce.

Were General Martins to finally accept the reality of Gitmo — that, given its history, nothing there can truly resemble justice — he might be able to lead even a recalcitrant Republican Congress, the administration in its last days, and the American public to the only realistic conclusion: that the military commissions will never work and it’s finally time to shut Gitmo down. After all, it is hard to imagine any system that would do worse than the one that, for a decade, has failed even to begin the trials of the men charged as perpetrators of 9/11.

Those attacks left an open wound that will not heal, not without actual justice. For the sake of the victims’ families, for the ability of the country to move on, for the very confidence of the nation in its judicial system, those defendants need to be tried and Guantánamo has proven itself incapable of doing so.

Still, all of us have to face another possibility: that the prison will not be closed in what’s left of the Obama years or in the presidency to follow; that this country will instead be left in the twilight zone of Gitmo and in a world where its values are the ones eternally associated with America; and that we will continue to be known as a nation willing to avoid justice, if not deny it outright. Even at this late date, closing Gitmo and moving the military commission trials back to federal court would help heal the wound that the war on terror inflicted on the country’s deepest identity — as a nation of justice for all.

Karen J. Greenberg, a TomDispatch regular, is the director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law School and author of The Least Worst Place: Guantánamo’s First 100 Days. Her latest book, Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State (Crown Publishers), will be published in May. Andrew Dalack, a research fellow at the Center on National Security, helped with this article.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse’s Tomorrow’s Battlefield: U.S. Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2016 Karen J. Greenberg Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.