What Really Stands in the Way of Closing Gitmo

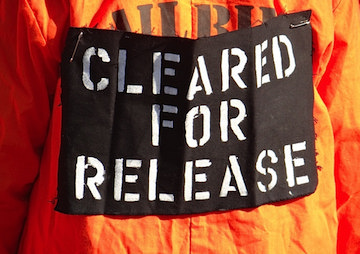

With nine months left until a new president is inaugurated, it has to be asked: Can the U.S.’ signature war-on-terror prison at Cuba's Guantanamo Bay ever be closed? An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

By the summer of his first year in office, Obama had announced that he would accept the distinctly un-American reality of indefinite detention and the military commissions as well, although in a new form still to be legislated by Congress. From then on, his presidency would remain eerily locked in the embrace of the Bush administration on Guantánamo and, promises or no, one thing was quickly clear: the president was not about to go out on a limb for the Gitmo detainees; he had other things to tend to (like a health-care proposal). Meanwhile, a task force appointed by the president determined that 48 detainees should indeed be kept in indefinite detention, 36 prosecuted, and the rest released via transfers to other countries.

Shrinking Gitmo

Given his promises, it was not exactly a record to feel proud of, but in his seven years in office, President Obama has at least made some headway in terms of the sheer size of the Gitmo population. Admittedly, the pace of releases has been abysmally slow. Dozens of prisoners have been declared no longer dangerous and yet left to languish in their cells. Meanwhile, diplomatic negotiations for their resettlement in countries neither so fragile that terrorism is a daily reality, nor likely to abuse them further dragged on (while congressional Republicans continue to fight on tooth and nail to keep them in place). Still, today there are “only” 80 remaining detainees, a third of the population in January 2009. Twenty-six of those have been cleared for release but are still awaiting transfer years later, while 44 continue to be held without charges in indefinite detention. Nine face actual charges before the military commissions.

Whatever the reduction in numbers, however, the camp stands essentially as it did under Bush, a monument to bad memories. It still has dozens of individuals locked away in a grim state of hopelessness, some cleared for release but doubting their transfers will ever occur, others having given up entirely and on hunger strikes — essentially trying to commit suicide.

Theoretically, the pace of resettlement for those already cleared for release could be speeded up and the Periodic Review Board, charged with deciding if an individual no longer poses a danger to this country, could meet more frequently to agree on releases among the relatively small number of detainees whose futures are still undetermined. Were that to happen (and it might), within months the population of Gitmo could be reduced to a relatively few detainees.

It’s worth noting that U.S. taxpayers continue to ante up a pretty penny to maintain Gitmo and its shrinking group of inmates in its present state. The cost to keep a detainee there in 2015 is estimated at between $3.7 million and $4.2 million a year. Were that population to be reduced significantly, those millions of dollars per detainee would only skyrocket up. The smaller the number remaining there and the higher the cost per head, the more likely that even a reluctant Congress might eventually agree to move them to the U.S., although “closing Guantánamo” will then mean bringing Gitmo practices — indefinite detention without charges, the most fundamental violation of due process imaginable — to the mainland.

Regressive Justice

That would leave one thing and one thing alone standing in the way of Guantánamo’s official end: the military commissions, and that would indeed be ironic. After all, unlike indefinite detention or torture, those commissions are a recognizable, if flawed, part of the American legal tradition, used during both the Civil War and the Second World War.

They have been marked by failure from the outset. The commissions were not initially on the minds of the Bush administration lawyers and officials who organized the war on terror, set up that Cuban outpost, and enhanced those classic torture “techniques.” In fact, offshore detention was meant to skirt the U.S. justice system almost entirely and get information from the captured men by any means necessary. The goal was clear enough: to fill in for the unfortunate lack of knowledge American intelligence services had about Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaeda network, their hideouts and training camps.

To give themselves leeway in terms of prisoner interrogation and treatment, the administration refused to consider those held there as prisoners of war (POWs), for fear that methods of interrogation would be restricted by the Geneva Conventions. Instead, they coined a term, “enemy combatants,” to create a category beyond the bounds of legality. To this day, U.S. officials speak of the remaining detainees at Gitmo as neither “prisoners” nor POWs.

Soon after the prison was set up, the Bush administration referred 24 of those “enemy combatants” to an ad hoc process which they began to call “military commissions” — until, in June 2006, the Supreme Court declared them invalid unless authorized by Congress (which then dutifully and hastily passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006).

All these years later, only eight prisoners have been convicted under the commissions that were suspended and then revived by Obama. Three of them, convicted before he took office, have since had their charges vacated or overturned. Put another way, you could say that the commissions are regressing in their goal to clear Gitmo’s cases. Once able to claim eight convictions, they can now count only five, and in the months to come, depending on a future decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, that number may be reduced further. In sum, the commissions have shown not the slightest progress when it comes to the mission of closing Gitmo.

There are, of course, federal courts in the U.S. with much experience in trying terror cases and a 100% conviction rate when it comes to major ones. To give Obama administration officials some credit, they did initially want to dump the military commissions for trials on the mainland and even moved one high value detainee, Ahmed Ghailani, to the federal courthouse in New York City. While his trial did result in a jury conviction on a single charge and a sentence of life without parole, the trial itself was seen by those who prefer to keep Gitmo open as proof that terrorists do stand a chance of going free in federal courts. Much of the evidence against Ghailani, tainted by torture, was excluded from the trial. While the jury knew neither about his torture nor the fact that he had been held at Guantánamo, Ghailani was acquitted on 283 of 284 counts. In a situation in which the phrase “courage of your convictions” would never be brought to bear, President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder backed down amid a torrent of criticism, and the military commissions continued at Guantánamo.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.