The Agonizing Reality Confronting the Post-Civil Rights Generation

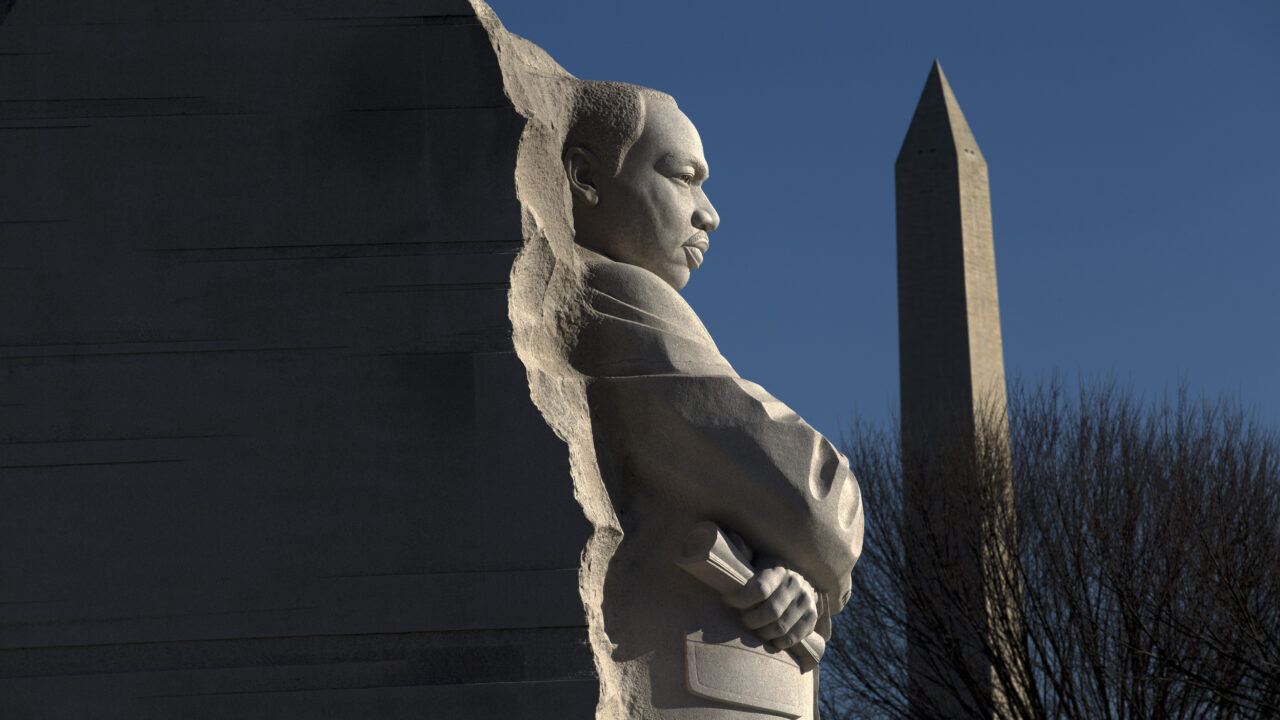

Reflecting on the systems that maintain racism and separatism in America. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

The youngest child of Martin Luther King Jr. died last month. Like me, Dexter King was 62, part of what I call the 1.5 generation. Born into a world of legal segregation, the last formal vestige of slavery, we came of age in a world without it. One-point-five is a term usually used to describe first-generation immigrants, but Black people fit the definition of internal immigrants. They spent the last century moving out of the South to seek places more hospitable to their presence; my people moved from Louisiana to Los Angeles for that reason. I always felt more fortunate than my forebears, whose stories about life in the old country fascinated and horrified me. How wonderful, I thought, that I had been spared the South and the racial madness that routinely separated my father and grandmother by skin color on New Orleans streetcars. My parents cautiously expected my generation, equipped with hard-won new freedoms, to continue changing the country for the better. I felt the same. My brave new life would redeem the old.

I was wrong. The 1.5 generation now carries the same grievances as previous generations, which remain valid even as they become harder to define amid a shifting new-century context. It turned out that the seismic change from segregation to a Jim Crow-free country benefited us less than white folks who were eager to drop the subject of racial justice as much as possible, preferably altogether. After the tumult of the ’60s, they were exhausted and not especially interested in fulfilling the promise of American democracy that MLK stood for. In this vacuum, the old conservatism and caste-ism that had defined the country for so much of its history reasserted itself, formalized in the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan. Those of us invested in the promise of democracy have been fighting headwinds ever since.

Far from creating a genuinely post-racial society, Obama’s presidency produced Donald Trump and Trumpism. It’s been agonizing to watch.

It’s not that the 1.5-ers didn’t experience transformation. We solidified the foundation of a Black middle class, one with unprecedented levels of education and agency. Disco democratized the dance floor. I attended an integrated public high school and made white friends, something practically forbidden to my parents. I felt part of the whole American zeitgeist of individualism and self-improvement; an illusion, to be sure, but to feel fully participant in the illusion seemed like progress. Previous generations of Black people were told they didn’t belong. I assumed I belonged, and those who didn’t think so were marginalized. I understood that racism and the grievances of the ’60s persisted, of course, but I understood them from my new position in the social and cultural order. The “we” that James Baldwin used defiantly and sometimes bitterly in his famous critiques of American morality now had meaning. We might argue over the details of racial justice, but we agreed that racism itself was fundamentally unworkable. Surely, we would not have to argue about that ever again.

This illusion has only recently begun to collapse. In the last few months I’ve had to acknowledge to myself what MAGA is doing: reviving racism and separatism as the true American way of life. Much of the country — including those I believed had gotten over that hump in the ’60s — is embracing the revival with gusto. This is emotionally devastating. Younger Black folk raised on the Black Lives Matter movement, Gen Y and Gen Z, are less naïve and better equipped to deal with ubiquitous inequality. For my cohort, MLK’s dream was not a speech but a directive that we took seriously; we were the first beneficiaries of a country reconfigured by the formal death of Jim Crow. It’s no accident that Obama, a 1.5-er born in 1961, believed he was uniquely qualified to bridge that gap between old racial fears and a new multiracial consciousness that propelled him into the White House. This was the basis of his Hope-in-America campaign that, for a moment, thrust our pioneering generation into the spotlight. But far from creating a genuinely post-racial society, Obama’s presidency produced Donald Trump and Trumpism. It’s been agonizing to watch.

Across generations, Black people struggle to maintain reasonable, sometimes radical expectations of change while continuing to perfect the increasingly fine art of survival.

The truth is that the Black repositioning post-civil rights was always precarious, subject to downgrading at any moment. In the ’70s, before I attended that high school (which has since resegregated) I went to a predominantly white elementary school that was integrated, briefly, before white folks abandoned it in droves. In college, I was baselessly accused of plagiarizing a term paper because, the very liberal professor insisted, people like me were constitutionally incapable of intellectual and literary competence. I remember feeling astonished, and then at a loss; my lifelong confidence in inclusion was shattered in an instant, with nothing to replace it. My generation never achieved economic stability, to say nothing of prosperity, the middle class notwithstanding. Those with good public sector jobs got through a kind of wormhole that closed up years ago. Today’s reenergized union movement reminds me that Black people never got a foothold anywhere in the private sector. Nor have we recovered from the monumental housing crash of 2009, when Black households lost more than half of their wealth, if it can be called that. And it’s looking grim for our children. On my block of aging Black folk who bought their homes back when homes were affordable on moderate incomes, young Black families simply can’t break into ownership, or even rentership. That leaves us ever more vulnerable to gentrification.

At this late date, none of us have arrived. Whether we’re 26 or 62, the Dexter generation or the alpha generation, we all remain in flux, still in the process of becoming. There is at least the familiar comfort of community in all this. Across generations, Black people struggle to maintain reasonable, sometimes radical expectations of change while continuing to perfect the increasingly fine art of survival. It may not be the dream we had in mind, but history once again requires nothing less.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.