What Really Stands in the Way of Closing Gitmo

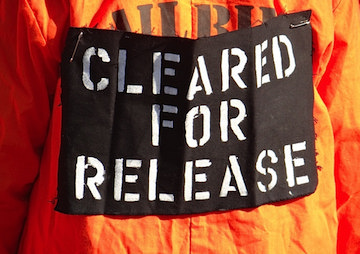

With nine months left until a new president is inaugurated, it has to be asked: Can the U.S.’ signature war-on-terror prison at Cuba's Guantanamo Bay ever be closed? An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.' Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

1

2

3

An activist at the White House in 2015 wears garb in protest of the U.S.’ Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba. (Debra Sweet / CC-BY-2.0)

Can you believe it? We’re in the last year of the presidency of the man who, on his first day in the Oval Office, swore that he would close Guantánamo, and yet it and everything it represents remains part of our all-American world. So many years later, you can still read news reports on the ongoing nightmares of that grim prison, ranging from detention without charge to hunger strikes and force feeding. Its name still echoes through the halls of Congress in bitter debate over what should or shouldn’t be done with it. It remains a global symbol of the worst America has to offer.

In case, despite the odds, it should be closed in this presidency, Donald Trump has already sworn to reopen it and “load it up with bad dudes,” while Ted Cruz has warned against returning the naval base on which it’s located to the Cubans. In short, that prison continues to haunt us like an evil spirit. While President Obama remains intent on closing it, he continues to make the most modest and belated headway in reducing its prisoner population, while a Republican Congress remains no less determined to keep it open. With nine months left until a new president is inaugurated, the question is: Can this country’s signature War on Terror prison ever be closed?

The “Forever Detainees”

Here then is a little dismal history of a place most Americans would prefer not even to think about.

In January 2002, President George W. Bush opened the Guantánamo Bay Detention facility. It was to hold, in Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s phrase, the “worst of the worst” in the War on Terror. Over time, its population rose to nearly 800 prisoners from 44 countries, some captured in Afghanistan, some traded for bounty payments by vindictive neighbors or hostile tribesmen, and some seized by CIA operatives in countries far from Taliban territory. The prison then held more al-Qaeda and Taliban followers than leaders, but many prisoners were neither: they had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. Recognizing this, within a few years the Bush administration sent more than 500 of the detainees back to their countries of origin or to other countries willing to accept them.

Then, in 2006, Bush made the lie of Guantánamo a reality. His administration finally transferred “the worst of the worst” to the by-then-notorious island prison. Those 16 individuals included five who stood accused of participating in the 9/11 conspiracy, and others who were believed responsible for devastatingly lethal attacks against American targets in the 1990s, including the American Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 and the USS Cole in the Yemeni port of Aden in 2000. All had been held for years in CIA custody in “black sites” in countries around the world. All had been subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which was, of course, the administration’s (and, in those years, the media’s) euphemism for some of the oldest torture practices known.

That move would prove a game changer. Instead of Guantánamo’s population shrinking into irrelevance and dwindling into obscurity, as it should have, the prison for the first time became exactly what Rumsfeld had promised it would be: a place for the most notorious al-Qaeda “high value detainees” (HVDs) that the U.S. held. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the “mastermind” of 9/11, and four others allegedly involved in planning or carrying out the attacks on New York and Washington were among them.

That same fall, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act aimed at assuring that Guantánamo would be a site not only for offshore detention, but for offshore justice as well. At some future point, Mohammed and the others were to be tried by the U.S. military in Cuba, not in American civilian courts in the U.S. For the first time, the military commissions, like the high value detainees, seemed to give Guantánamo definition (other than simply as a site of abuse, mistreatment, and injustice) and the possibility, in the context of the war on terror, of forward momentum. Those not released could now be tried. And yet by the end of the Bush years, only three prisoners, none of them HVDs, had been successfully convicted — fewer, in other words, than the five who died in custody there in those years.

That should have been revealing enough for conclusions to be drawn. It turned out that even a secretive, militarized, legally compromised system of “justice” couldn’t successfully bring to trial individuals involved in the crime that launched the new century, when the major evidence against them often came from brutal forms of torture. As a result, most of the Guantánamo detainees had settled into a familiar state of limbo by the time Barack Obama took office in January 2009. At the time, 242 detainees were still in custody there and those military trials were going nowhere fast. The new president arrived on a white horse, full of promises about ending the stasis at Guantánamo and ready to make sense of things. He promptly promised to close the prison for good and suspended the military commissions.

That left the problem of somehow resolving the unsettled status of the various detainees then in custody at Gitmo, individuals who essentially fell into three categories: those deemed not to pose a danger to the U.S. who were to be released; those considered too dangerous for release but — thanks to tortured testimony — not prosecutable even in military courts and were to be kept in indefinite detention (a group Miami Herald reporter Carol Rosenberg aptly termed “forever prisoners”); and those who would someday be tried by some version of the suspended military commissions.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.