‘Inside Out’ Turns Pixar’s Usual Formula on Its Head

A female protagonist? And a focus on emotion? What’s going on here? Maybe the animation company has learned some life lessons. Disney.com

Disney.com

“Inside Out,” a Pixar animation that prompts smiles of recognition and belly laughs of the fall-on-the-floor sort, is set largely in Mission Control of a brain that belongs to an 11-year-old. Her name is Riley.

“Finally!” I can hear you exclaim. “Is this the answer to the question ‘What in the hell is going on inside my daughter’s head?’ ” Insofar as it shows how various brains — tweenage, adult, canine and feline — are wired, then yes. Watching “Inside Out” produces an exquisite sense of well-being, so much so that you might say that this film from Pete Docter and Ronnie del Carmen is cinematic serotonin.

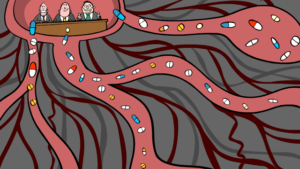

Riley’s brain trust resembles a panel of NASA scientists coordinating a complex interplanetary expedition. In her case, it’s an interstate move from her native Minnesota to San Francisco, where the hockey star is relocating with her parents. If you remember the “What Happens During Ejaculation?” scene of Woody Allen’s “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex,” Mission Control looks like that, only PG-rated.

“Inside Out” segues gracefully between Riley’s external pressures and her internal means of coping — or not — with the challenges of her transition.

In what the Pixar/Disney flacks are calling “an emotion picture,” Riley’s moods and memories are controlled by five feelings. Joy (voice of Amy Poehler) is relentlessly upbeat and bossy, an alpha-girl Tinkerbell. Sadness (Phyllis Smith) is morose and apologetic — naturally she wears blue. Disgust (Mindy Kaling), Fear (Bill Hader) and Anger (Lewis Black) have hair-trigger tempers, bicker among themselves and aren’t ones for self-control or planning ahead.

Each day of Riley’s memory gets stored in what looks like a glass marble, color-coded for the day’s dominant emotion. (Neon green for Joy, blue for Sadness, red for Anger.) As foreshadowed, Riley loses her marbles at a critical point.

From the film’s early scenes, Joy and Sadness are set up as adversaries, with Joy’s soaring optimism generally outpacing Sadness’ lead-footed gloom. Yet when Riley (voice of Kaitlyn Dias) arrives in the city of fog, candy-colored Victorian houses and broccoli pizza, her customary resilience deserts her. The combined stress of new home, new school and not easily making new friends turns the outgoing ’tween into an introvert.

What Riley doesn’t know is that Sadness is tired of being dominated by Joy. By inadvertently touching Riley’s core memories, Sadness turns the cheery green marbles into miserable blue ones. In trying to win these internal color wars, Joy wrangles with Sadness, leading both of them to fall from Mission Control into another part of Riley’s brain. This leaves Anger, Disgust and Fear at the controls. Which, in turn, leaves Riley with a very short fuse.

The film’s dramatic conflict is in how perceived opposites Joy and Sadness team up to get back to the Control Room. It seems to be a vaster distance from Riley’s subconscious to Mission Control than from Minnesota to California, but their journey is fraught and pretty exciting, especially when they get lost in the part of the brain governing abstract thought and their bodies morph from 3-D to cubistic 2-D to line drawings.

While the film’s visual jokes are as funny as they are imaginative, the humor and inventiveness are yoked to an unusually poignant narrative. Given that Docter’s previous movies include “Monsters, Inc.” and “Up,” this is no surprise. As with both of those efforts, Docter and Carmen focus on how the protagonist sails through a stormy life passage.

Like the child in “Monsters,” who learns not to be afraid of the ogre under the bed, and the geriatric gentleman in “Up,” who loses his beloved wife and gains a surrogate son, Riley is in for a life lesson. Joy and Sadness are not opposites but the extremes on one continuum. And just as the sourness of lemon juice makes the apple pie taste sweeter, so the way that sadness derails Riley heightens the delight of getting her back on track to joy. Put simply, it’s OK to be sad.

Maybe Pixar has learned a life lesson, too. While most of its previous films have purveyed male characters, this one centers on a female. What’s more, it focuses on emotions, thought to be anathema at a box office geared to action.

“Why a girl?” you may wonder. Docter is glad you asked. Recently he said, “The reason is that research has found that no one is more socially attuned and keyed in on expressions and little interactions than a girl aged 11 to 17. On the other hand, no one is less socially attuned than an 11-to-17-year-old boy.”

“Inside Out” promises to tickle both groups — not to mention their parents and grandparents.

Postscript: An antecedent of “Inside Out” is the 1943 Disney short “Reason and Emotion,” which was nominated for an Oscar. Interestingly, this anti-Nazi propaganda film argues that reason should be in the driver’s seat and emotion should always follow it. Notice the gender-coded emotions and their appetites: Men crave sex, and women, food.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.