The Call for Reparations Rises Again

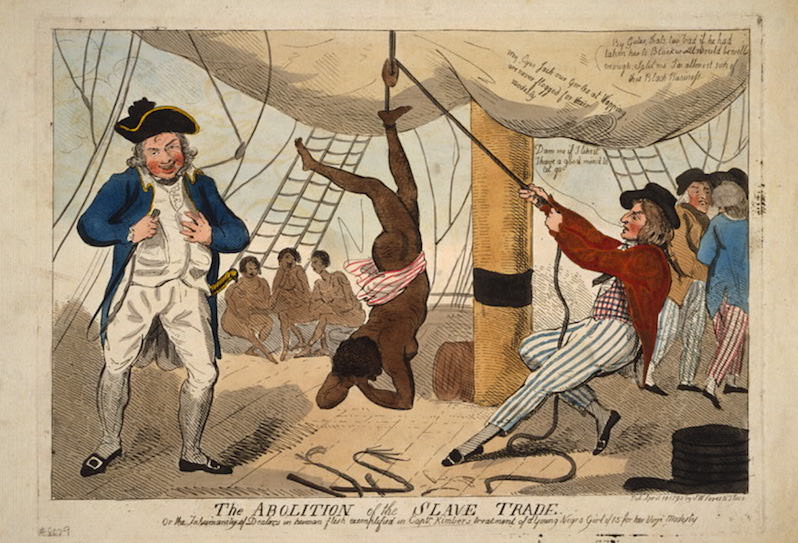

In 1865, former slaves first heard the broken promise that they would receive "40 acres and a mule" to start their new lives. Now, 150 years later, the movement seeking compensation and healing for the slaves' descendants is coming back to life.In 1865, ex-slaves were promised "40 acres and a mule." Now, 150 years later, the movement to win compensation for their descendants has returned, with a focus on healing. An African girl is tortured aboard a slave ship in this Isaac Cruikshank print from 1792. (Library of Congress)

An African girl is tortured aboard a slave ship in this Isaac Cruikshank print from 1792. (Library of Congress)

Each seasick night aboard the Zong, the crewmen must have dreamed of being back in England at last, with their purses full of gold. The ship’s two-month voyage had been an arduous one. The supply of drinking water was running dangerously low, and many on board were gravely ill, including Capt. Luke Collingwood.

In fact, Collingwood was so deliriously sick that he could not navigate properly, and the sailors — who had believed they were bound for Black River, Jamaica — ended up overshooting their destination by some 300 miles.

Panic set in when they realized their error. Survivors would later testify that they had feared there would not be enough water to sustain them and their valuable cargo for the entire way back. This is how, they claimed, they came to the damnable decision — in late November and early December of 1781 — to unload a sizable portion of their cargo, tossing overboard more than 130 West African prisoners and leaving them to drown in the blue depths of the Caribbean Sea.

The murderers eventually landed in a London court — in a case known as Gregson v. Gilbert — not to face charges for the massacre but in a dispute over an insurance policy taken out on that human cargo.

When the 200 or so remaining Africans had been sold and the crew had returned to England, the expedition’s leaders filed an insurance claim to recoup some of the money they had lost on the people they had killed. Understandably, the insurers refused to honor the claim, but at trial a jury found that they were in fact legally bound to do so — just as they would have been if the cargo had consisted of horses. (The plaintiffs later appealed, and the court agreed that a new trial should take place, yet for some reason none ever did.)

Today, almost no one in the United States has heard of the Zong massacre, though among academics it is known as one of the most notorious incidents in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Even in Black River, Jamaica, just a single, lonely plaque stands in memory of the nameless Africans who lost their lives before reaching shore. Neither the slave traders nor the insurers who profited from the Zong expedition were ever held accountable.

It is now more than two centuries later, but not everyone has forgotten.

Jamaica and at least 13 other members of the Caribbean Community (Caricom) have issued a renewed call for reparations for the descendants of slaves, like those who survived the Zong massacre.

In 2013, Caricom leaders voted to establish a regional reparations commission. Its mandate is to make the case that European governments — the United States government is not mentioned — owe the descendants of black and indigenous peoples, not only because their ancestors were victims of torture, enslavement and even genocide but because the consequences of those atrocities can still be seen and felt in the prevailing social and economic inequalities of 2015. After all, those governments condoned and encouraged the slave trade, which enriched their economies for centuries.

Significantly, the Caricom nations are not seeking payments to individuals at all. Instead, their short list of 10 demands includes things like an apology from Europe’s former colonial powers, economic and technological development initiatives, debt cancellation, public health assistance, and settlement in Africa for any blacks who want to move there.

Perhaps most important, the list includes a demand for education and psychological rehabilitation. It reads:

For over 400 years Africans and their descendants were classified in law as non-human, chattel, property, and real estate. They were denied recognition as members of the human family by laws derived from the parliaments and palaces of Europe. This history has inflicted massive psychological trauma upon African descendant populations. This much is evident daily in the Caribbean. Only a reparatory justice approach to truth and educational exposure can begin the process of healing and repair.

The Caribbean’s call appears to have reached the shores of the U.S., where interest in reparations waned after 9/11 and the subsequent election of a black president:

Last December, Sir Hilary Beckles, the vice chancellor of the University of West Indies, spoke on reparations before the United Nations General Assembly. And this year, the entertainment world saw the premiere of the science-fiction film “No Boni,” about an experiment to administer reparations in the form of a mind-altering drug.

In New York City, a three-day reparations summit began on April 9, exactly 150 years after the end of the U.S. Civil War and the birth of the nation’s broken promise to provide “40 acres and a mule,” a kind of reparations, to its former slaves. (That promise — first voiced by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and later echoed by Reconstruction officials like Clinton B. Fisk and Republicans eager to capture black votes — was one that the historian Walter Fleming said some older blacks were still waiting and hoping to see fulfilled in 1906, four decades after the war’s end.)

The New York summit, organized by the nonprofit Institute of the Black World 21st Century (IBW), welcomed delegations from 10 Caricom countries, Belgium, Belize, Britain, Canada, France, Martinique, the Netherlands and Sweden. Roundtable discussions and performances were scheduled, along with speeches by the actor Danny Glover, the Rev. Jesse Jackson and the famed Harvard Law professor Charles Ogletree. Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., was also honored for his decades of work championing reparations in the U.S. Congress. Many American activists are looking to model a national reparations agenda on the one outlined by Caricom — including the demand for psychological healing. In a statement, IBW President Ron Daniels said, “Africans in America are due compensation to repair the physical, cultural, spiritual and mental damages inflicted by the holocaust of enslavement.”

I asked Don Rojas, IBW communications director, why his organization had chosen to organize the summit now, when — as many are likely to argue — slavery was too long ago to matter and when the American people have as a second-term president a black man — who, by the way, opposes reparations.

“We don’t live in a postracial era just because we have elected a black president — just look at the Fergusons of the world,” Rojas told me, referring to the Missouri city that has been a hotbed of protest since the police killing of an unarmed black man there last year. “Look at the epidemic of police brutality. Look at the ravages of the war on drugs. Look at the incarceration rate among young African-American males.”

Still, a major obstacle for the movement is that too many Americans lack a sense of historical perspective.

“History does matter, and race does matter,” Rojas said, “and we have a tendency in this country to not recognize the connections between our collective past and our collective present.”

To help remedy that problem, IBW is launching what it calls the National African-American Reparations Commission to spearhead education and advocacy efforts throughout the United States. To finance its commission’s activities over the next year, IBW needs to raise $150,000 in private donations — because, Rojas said, “We’re not going to get any government funds or corporate funds or even foundation money.” Those activities, he hopes, will include a nationwide series of town hall meetings — welcoming people of all colors to discuss and promote reparations and to gather ideas that could be incorporated into a national reparations program.

IBW’s vision is one focused primarily on civil society and not corporations.

That is a concern for Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, who made her name during a previous blossoming of the reparations movement, in the early 2000s, when her nine class-action lawsuits sparked the enactment of slavery-disclosure laws across the country and forced big-name companies like Aetna, Wachovia and JPMorgan Chase to acknowledge their historical links to slavery.

Farmer-Paellmann fears that IBW and others joining today’s renewed reparations movement will neglect to hold corporations responsible for their involvement in the slave trade.

“If we came together as a community in putting more pressure on the corporations, then the government would act,” she told me. “If you’re a company that lied about your role in slavery, you’re liable for consumer fraud. We have plenty of evidence to show that companies were lying about their role in slavery.”

The issue is a deeply personal one for Farmer-Paellmann.

Raised in Brooklyn, she grew up hearing her grandfather tell stories about their ancestors Abel and Clara Hinds, an enslaved husband and wife who ran away from a South Carolina rice plantation. As her grandfather recounted that history, he would often remark: “They still owe us 40 acres and a mule.” As a youngster, Farmer-Paellmann did not realize what he was talking about. But years later, as a law student researching archival records, she stumbled upon an insurance document detailing how much money a policyholder could expect to recover upon the death of a 10-year-old slave. Some time later, she found an Aetna insurance policy on one of her own ancestors — none other than Abel Hinds.

Farmer-Paellmann was driven for years to continue her legal fight. Then in 2007, the Supreme Court declined to review the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in her Brown and Williamson case. The appeals court had ruled that the plaintiffs lacked standing and that the statute of limitations had run out. For want of about $15,000 to pay the other members of her legal team, she told me, she was forced to discontinue litigation. Now, she is a stay-at-home mother, but she hopes others who are just joining the reparations movement will take up where she left off.

“I’ve proven that this is a strategy that can work,” she said, “and it’s up to other people to recognize the strategy and pursue it rather than try and reinvent the wheel. They just need to look at the court decisions.”

While Farmer-Paellmann thinks IBW and Caricom should emphasize corporate accountability more, one aspect of their agendas that she does support is their demand for education and healing.

In Germany, Farmer-Paellmann points out, Holocaust studies are a significant part of the curriculum, and she thinks an analogous requirement that American students learn about the history of slavery would do much to further the reparations movement.

“Education has to come first,” she said. “Too many are confused about what happened, when, and who is responsible for the compensation. Germans are clear about that,” thanks to their efforts to teach the history of the Nazi era.

I heard a similar view expressed by Randall Robinson, the founder of the human rights organization TransAfrica and the author of several best-selling books, including “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks.”

For Robinson — who grew up in Richmond, Va., during segregation — economic remuneration and the healing of psychological traumas must go together. “I’m 73 years old, and I’m still scarred by my childhood,” he told me in a telephone conversation from his home on the island of St. Kitts.

Although he supports the establishment of panels to study the historical injustices of slavery and its ongoing effects — and to assign those effects a value in dollars — he thinks that more than money is required because so many blacks have suffered “a psychological injury” and lack a sense of historical identity.

Many blacks are not even aware that the White House was built by slaves, he said, and not so long ago, during a visit to Virginia Union University, a historically black school, he was shocked to learn that no course in African history was being offered.

“It’s not a matter of money,” he said. “It’s the restoration of the psychological health of a people. It is so incredibly essential that we do this. You have to teach and record your story, and we have a glorious story. Don’t you know that the pyramids were built by black Egyptians? Even National Geographic had a piece on that.”For me, a black man in my mid-30s, Robinson’s assertion resonates. I don’t remember learning a great deal about the history of slavery until I was in college, and even then only because I chose to do so — not as a prerequisite for my degree. Of course, no college course ever taught me anything about my own family’s ties to slavery. It took many dedicated years of searching through crumbling, old books and microfilm to begin to piece together my personal story. Some of what I found was incredibly painful, but all of it gave me a feeling of wholeness and connectedness to the past that I had never felt before.

Like Farmer-Paellmann, I found a surprising connection to a big-name company. In my case, it was not Aetna but JPMorgan Chase & Co., which issued an apology 10 years ago for its links to slavery.

In my research, I discovered that an ancestor of mine named Charles Parent — my fifth great-grandfather on my mother’s side — was a white slaveholder and War of 1812 veteran who raised cattle and manufactured bricks in St. Tammany Parish, La., and whose sister Francoise married Gov. A.B. Roman.

In 1838, Grandpa Parent took out a mortgage loan from the Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana — a predecessor of JPMorgan — for $24,300. By today’s reckoning, the loan would be worth more than half a million dollars.

As collateral, the bank accepted his sprawling, 2,000-acre plantation and 29 enslaved men, women and children. Parent’s slaves probably never knew that their lives had secured such a large fortune for their master. In any event, none of them ever saw a nickel of the money.

Under the Nuremberg charter — to which the United States is a signatory — enslavement is defined as a crime against humanity. In addition, a 1968 U.N. convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court — both of which have sadly not been ratified by the U.S. — say that there is no statute of limitations on such crimes.

In other instances, the U.S. and Europe have shown a willingness to acknowledge and pay for heinous acts against ethnic groups.

For example, the U.S. federal government has paid Japanese-Americans who were unjustly imprisoned during World War II, and the state of Florida has paid reparations to survivors of the 1923 Rosewood massacre. In 2013, Britain agreed to compensate Mau Mau people tortured during its colonial administration of Kenya, and for more than six decades Germany has been compensating Holocaust survivors.

When it comes to American slavery, however, the problems are more nettlesome: The original victims are now long dead, and pinning down the identities of individual slaves’ descendants is extremely difficult and often impossible. Yet we should not let those challenges stand in the way of an honest conversation about slavery and how to address its living consequences.

As I think of the slaves on my ancestor’s plantation, I weep for the children: Zacharie, Elick, Bob, Emiline, Pauline, Josephine, Maria, Henrietta and Eliza. Still, I take some comfort in the fact that most of them probably lived — through daily backbreaking labor and devastating trauma — to see the end of the Civil War and to have a taste of freedom.

But what does freedom mean without justice?

Channing Joseph, based in San Francisco, is one of Truthdig’s editors as well as an MTV News correspondent covering social justice issues. His stories have also been featured in The New York Times, The International Herald Tribune, The Atlantic, U.S. News & World Report, Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, People, CNN and BET.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.