Reconciling ‘The Help’ With the History

There has to be a lingering suspicion (and hatred) that "The Help" cannot bear to contemplate It wants us to believe that all involved learned their costly lessons in the Mississippi of 50 years ago.

The time is the mid-’60s. The place is Jackson, Miss. The principal activity in the movie consists of a young woman named Skeeter (Emma Stone) persuading the town’s black maids to recall the racism visited on them by the mostly young white women for whom they work as domestics. The aim, ultimately, is to write a book exposing the genteel, but deadly, patronization that slowly wearies their souls. From this conceit Kathryn Stockett fashioned “The Help,” a mighty best-selling novel that screenwriter-director Tate Taylor has now turned into an episodic and rather inert movie.

The white women, Skeeter aside, are mostly airheads, preoccupied by their bridge games and cotillions, and by providing separate but equal bathroom facilities for the women who work for them. They actually visit more outright contempt on Celia (Jessica Chastain), an outlander who lacks all domestic graces until she is taken in hand by Octavia Spencer’s Minny, who basically teaches her how to fry chicken and keep house for her clueless husband.

Minny is more or less typical of the film’s black population. She is patient, wise and essentially a silent witness to the nonsense of her white mistress, who turns out to be more educable than the rest of her sisters. Minny will win her for righteousness simply by showing what to do around the house, not by moralizing about how she should behave.

But the center of the film (and the chief reason for seeing it) is Viola Davis as Aibileen, who works for Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard), by far the meanest of the ladies who lunch. Aibileen is a third generation maid, a woman who has loved all the children she has cared for and raised — including Hilly’s child, whom she is determined to save from her mother’s ignorant folly. She is a patient, silent, watchful woman, yet she is also the first responder to Skeeter’s plea for an interview that will tell the real story of The Help. She also recruits the rest of the women who tell the inside stories that compose the best-selling book that Skeeter eventually writes.

There is some melodrama in their tales, though most of them are told rather than acted out before us, and a little bit of quiet revenge as well. And when Aibileen finally opens up, her long-withheld passions tumble forth not so much with force of revelation but in the matter-of-fact voice that marked Davis’ performance in the film’s early going. They are the more powerful for her restraint.

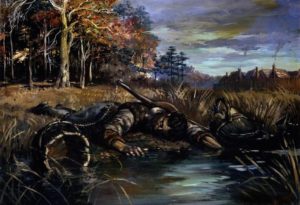

Yet “The Help,” despite her efforts, and those of the generally excellent cast, does not quite come off. We see the effects of the steady drip-drip-drip of unthinking prejudice. We appreciate the occasional rebellious acts of Jackson’s underclass, and the murder of Medgar Evers adds a note of real-world urgency to the storyline.

But it is not quite a game-changer. The movie is, for all its well-made slickness and sniping racism, too genteel. It is aimed at a feel-good ending. Skeeter’s book is published and it briefly discomfits Hilly and her friends. But you don’t feel it changes them in any meaningful way — with the possible exception of Skeeter’s mom (Allison Janney), who at last comes to appreciate her daughter’s independent spirit.

The movie rarely gets at the things that truly hurt and distort the relationships between an upper class and an underclass. It is all hominy grits instead of true grit, aiming finally at a foretold reconciliation that rings false. There has to be a lingering suspicion (and hatred) that “The Help” cannot bear to contemplate. It wants us to believe that all involved learned their costly lessons in the Mississippi of 50 years ago. And maybe on the surface that is true. But long-held silences hurt and scar — and abide — while manipulated happy endings simply leave audiences applauding smugly, as they did at the showing of “The Help” I attended: “Oh, good — that worked out nicely, didn’t it?”

Well, I don’t think that’s so. Few are alive who lived in Mississippi a half century ago. And doubtless most of them have made their peace with the bad old days. But in their sleepless nights I suspect that the pain and stupidity that the black women suffered in that time and place are not entirely silenced — much as Ms. Stockett and Mr. Taylor wish that they were so. History falsified is, in some ways, worse than no history at all.

Richard Schickel, whose celebrated and prolific career spans 50 years, has been the film critic for Time and Life magazines, has written more than 20 books and has produced, written and directed numerous documentaries.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.