Dugald Stermer Wanted to Change the World

Dugald Stermer, illustrator and visionary art director of Ramparts magazine, the legendary San Francisco muckraker, died last Friday after a long illness He was 74The visionary art director of Ramparts magazine died last Friday after a long illness.

Dugald Stermer, illustrator and visionary art director of Ramparts magazine, the legendary San Francisco muckraker, died last Friday after a long illness. He was 74.

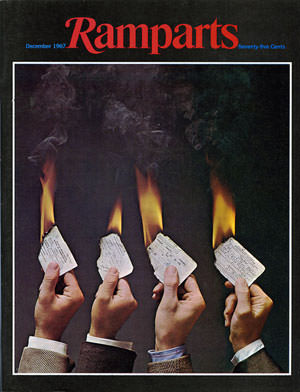

Stermer started at Ramparts in 1964, when it was a 2-year-old Catholic literary quarterly that resembled, in his words, “the poetry annual of a Midwestern girls school.” But as Ramparts began running more controversial content, Stermer transformed its look and earned the respect of publisher Warren Hinckle and editor Robert Scheer. Between 1966 and 1968, the three produced a magazine that, according to The New York Times, restored the lapsed institution of muckraking, put showmanship back into journalism and gave radicalism a commercial megaphone.

Stermer’s art direction was a critical part of that achievement. Ramparts became the first “radical slick” by combining blockbuster investigative stories with high production values, including color, photographs and glossy paper. That combination supercharged the magazine’s circulation and heightened its impact. When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. came upon a 1967 Ramparts photo essay called “The Children of Vietnam,” which documented the civilian casualties of U.S. bombing in Vietnam, he immediately decided to come out against the war. King wasn’t the only one affected by that piece; Stermer later said that laying it out was “just about the nastiest job I’ve ever had.”

Stermer left Ramparts in 1970, and the magazine folded in 1975. But Stermer’s influence in the magazine world lives on — most obviously at Rolling Stone, which was founded by Ramparts alumni Jann Wenner and Ralph Gleason in 1967. With Stermer’s blessing, Wenner lifted design elements from Ramparts, and some still appear prominently on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Born in 1936, Stermer grew up in Los Angeles. “I was a beach boy, your basic ’40s and ’50s kid,” he later said. “I liked playing cowboys and drawing pictures.” In his youth, he was something of a hood. “My image was surly, leather-jacketed, the white T-shirt with rolled up sleeves, the Levi’s hanging low. A nasty little teenager who worked in a gas station, so I was greasy on top of all this.”

But a high school teacher noticed Stermer’s talent as a cartoonist and encouraged him to attend college. He studied art at UCLA and worked for two years in a Los Angeles design shop before joining a Houston firm.

In Texas, Stermer met San Francisco advertising guru Howard Gossage, who was helping Hinckle juice up Ramparts. Stermer had no magazine experience, but Gossage arranged for an interview. Stermer learned that founding publisher Edward Keating had enough credit for only two more issues. But Stermer didn’t want to design corporate reports forever, so he packed his young family into his Volkswagen bus and headed for the Bay Area. He soon became a key player at the magazine.

“I was pretty intransigent about what I did, a ‘my way or the highway’ sort of thing,” he recalled. “I learned early that the person who gets there earliest and leaves latest makes all the decisions. Any territory you could defend was yours.”

His easygoing manner and workhorse habits tempered Hinckle’s extravagance and short-attention span. Like Hinckle, Stermer was a rebel, not a radical, and that quality helped keep the magazine from descending into rigid doctrine.

For Stermer, the fact that Ramparts was located in California was crucial. Because the magazine wasn’t based in New York, it was never expected to succeed. For this reason, Gossage said later, the Ramparts staff was like a troupe of dancing bears: Their technique was less important than the fact that they could dance at all. But those low expectations allowed Stermer to innovate, and he made the most of his liberty.

Stermer didn’t read magazines or the alternative press, so he had no preconceptions of what Ramparts should look like. Mostly he was guided by his UCLA professor’s dictum that the best design is never noticed. To emphasize the magazine’s message rather than its look, Stermer set every line of type — the captions as well as the text — in Times Roman. Drawing on local styles, especially those developed by San Francisco printers Edwin and Robert Grabhorn, he produced an elegant design that grounded the magazine’s explosive stories and irreverent tone.

“It was a conscious choice to just use one typeface, and make the design very simple,” he said in 2009. “It had nothing to do with budgets, although we never had any money. … I wanted the magazine, page-to-page, issue-to-issue, to feel like chapters of a book, and, considering our content, to look credible.”

At its peak, Ramparts received the prestigious George Polk Award for excellence in magazine reporting. More established magazines began to emulate Stermer’s approach, and Esquire tried to hire him. But he declined the offer, which would have paid him well but diminished his artistic control.

Stermer left Ramparts when its new editors, David Horowitz and Peter Collier, ousted Robert Scheer. (Hinckle had already left to found Scanlan’s magazine, where he first matched Hunter S. Thompson with illustrator Ralph Steadman.)

Stermer pursued a freelance career, first as a magazine designer and then as an illustrator. He drew a wildlife series for the Los Angeles Times; worked on campaigns for Levi’s, the Iams Company, the San Diego Zoo, Jaguar Cars Ltd., BMW and Nike; and created editorial illustrations for Time, Esquire, The New York Times, The New Yorker, GQ and Rolling Stone. He designed the Olympic medals for the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, and the State Department commissioned him to design the 2009 Earth Day poster. In 1986, he was the subject of a solo exhibition and retrospective at the California Academy of Sciences, and he gave the keynote addresses at the International Conference of Natural Science Illustrators in 2000 and the International Conference of Medical Illustrators in 2001.

Stermer taught illustration for many years at the California College of the Arts, where he was a distinguished professor and chaired his department. He was appointed to the San Francisco Arts Commission in 1997 and served on the Delancey Street Foundation’s board of directors for more than 30 years. (The foundation is a residential self-help organization for former substance abusers, ex-convicts and the homeless.) He was the author of four books: “The Art of Revolution” (1970) with Susan Sontag, “Vanishing Creatures” (1981), “Vanishing Flora” (1995) and “Birds & Bees” (1995).

In a 2010 interview, Stermer was asked about his career.

“As Howard Gossage used to say, ‘The only fit work for an adult is to change the world.’ He said it straight-faced, and while other people might laugh, I always have that in the back of my mind,” Stermer said. “I don’t walk around with my heart on my sleeve, but I do feel that using our abilities to make things better is a pretty good way of spending a life.”

Peter Richardson is the author of “A Bomb in Every Issue: How the Short, Unruly Life of Ramparts Magazine Changed America.” It was an Editor’s Choice at The New York Times and a Top Book of 2009 at Mother Jones.

Correction: This article originally reported that Stermer was 75 when he died. He was 74.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.