How Twitter Turned Journalism Into a High School Cafeteria

The premise of Web 2.0 was always toxic, but the peer pressure it exerted on journalists was especially destructive. Image: Adobe

Image: Adobe

The following story is co-published with Freddie deBoer’s Substack.

This New Yorker piece from Sheon Han mourning the end of Twitter is, well, it’s something. Look, I don’t begrudge an ex-employee sharing such an idealized vision of what his old company was. Certainly not considering the circumstances. But that rose-colored perspective hints at the fundamental problem with not just Twitter but the Web 2.0 principles that underlie it, which Han’s affection seemingly prevents him from understanding. Elon Musk is now a problem with Twitter, but even had the company been bought by some benevolent philosopher king, the core dynamics of a constant mass-broadcasting service for everyone would be deeply unhealthy. “Everybody in the same room all the time” social networking is problematic on its face and uniquely pernicious to journalism and media. If Twitter as we knew it really is over, this is a great time for the industry to finally grapple with what it has wrought. In fairness to Han and others, it’s not Twitter itself; in a different universe, some other social network that exposes everyone to each other’s opinions all the time might have wrecked media. In this one, it was Twitter. But the basic concept itself is inimical to what journalism and commentary has to do, no matter the name of the network, who owns it, or what its terms of service are. Forcing everyone into one discursive space inevitably creates peer pressure and conformity, in an industry where independence of thought has always been a treasured virtue.

If Twitter as we knew it really is over, this is a great time for the industry to finally grapple with what it has wrought.

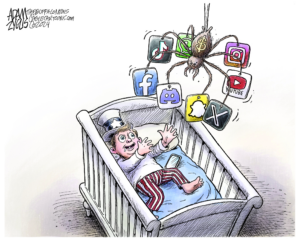

Very early in Twitter’s rise, it became a matter of holy writ that writers, journalists, editors, pundits, and everyone else involved in the reporting and opinionating business had to tweet. Even when I started writing for a public audience in 2008, when the service was only a couple of years old and the blogosphere was still puttering along, the idea that you simply had to be on Twitter was already growing, and in a few years became inescapable. If you didn’t tweet, as a writer, you didn’t exist. This wasn’t just a media phenomenon, either. I went through grad school in the early 2010s, and you already heard then that Twitter was becoming mandatory even for academics; professors at conferences would frequently ask you for your “at.” The message was relentless: if you weren’t on Twitter, you weren’t part of The Conversation, and you couldn’t get your work out there, regardless of what kind of work it was. (Hence the rise of, for example, Twitter realtors and Twitter life coaches and Twitter nutritionists.) And, indeed, everybody being in the same room together all the time did make it easy to share your work, and there was a chance it would be amplified and echoed across the reach of the network. There are great pieces that I found on Twitter that I probably would never have read otherwise. But I’m afraid most every other consequence was a bad one.

You see, it turns out that when you put everyone together in the same space all the time, all of the bad dynamics of in-group behavior are suddenly applied to vast populations. A high school cafeteria might house the entire school at one time, but everyone breaks out into different tables that are social divisions as well as physical ones. This is natural; a ceaseless cacophony of innumerable voices is unpleasant in and of itself, and it leads to a kind of overt social conditioning that’s creepy and unhealthy. Being aware of everyone’s thoughts means being aware of what they praise and what they criticize. And when you’re always aware of the opinions of your peers (or, even more, the people you aspire to see as yours peers) this can’t help but influence how you act and what you believe and what you write about. Nothing about this is remotely complicated or hard to believe. If you’re someone looking to get a staff job or a freelance writer who wants to publish in fancy publications, and the editors and writers for those publications are all in the same room, and they’re constantly letting everyone know what they like and what they don’t, how could that not influence what you pitch?

This basic mechanism for creating conformity was right out in the open; you could see people bend to the popular consensus in real time. If you said something people liked, they’d take a fraction of a second to hit that fav button. If you said something unpopular, people would yell at you, like really yell at you! For the average person, if those yelling people are your professional peers, that’s going to influence your work. It just will.

It turns out that when you put everyone together in the same space all the time, all of the bad dynamics of in-group behavior are suddenly applied to vast populations.

There have always been peer-group pressures that breed conformity, at any time and in any industry. What the rise of the social internet did was to a) scale up the number of people applying those pressures, b) make the application of pressure a potentially all-day affair, and c) pull not only professional values and concerns into consideration but also artistic tastes, slang, sense of humor, and similar. I’m sure there was a lot of concern for one’s reputation among peers within any given newsroom at any given paper, and these could not be said to have no influence on what got published. But that still meant that you were getting pressured by dozens of people instead of thousands, you went home at night and were free from those opinions, and once at home your tastes in TV shows or music weren’t being observed and judged. The social internet changed all that. Suddenly you weren’t just concerned with your reputation among your immediate peers at your workplace and what would appear on your resume, but with how your entire industry might perceive an offhand comment. Suddenly you weren’t just feeling the pressures of surveillance from 9 to 5, but also while you rode the subway in the morning and while you relaxed in front of a movie at night. Suddenly you weren’t just concerned that professional peers thought your work was strong, but also that they felt that you liked the right shows and told funny jokes. And, crucially, you also let them know that you liked what they were doing too.

Many are dismissive about this subject, I think because it makes people uncomfortable. Peers in media (if I can be said to be in media) have tended to wave away my complaints about Twitter by saying that it’s not a big deal and they don’t take it that seriously. But I’d always go and look at their accounts and find that they’d been tweeting an average of fifteen times a day since 2008, and the immediate question has to be, is it really credible that you would do something so often for so long if it meant nothing to you? It’s very easy to look at someone’s feed and see that they wake up first thing in the morning and tweet and tweet right before they fall asleep at night and tweet the whole time in-between. And, indeed, the pretense that something isn’t important to you, when your behavior clearly shows that it is, can only serve to make subtle influences like peer pressure more dangerous. I’ve said it many times, and people have gotten hepped up about it many times, but I still think that it’s true – journalism and writing and punditry and similar tend to attract those who are still, like the bee girl in the “No Rain” video, looking for their tribe. That’s profoundly understandable and human. But that’s also precisely the trouble: one thing the massively-social internet has done has been to erase the line between drawing validation from a limited intentional community of peers and seeking that validation from everyone. Precisely because the desire to be liked is so visceral and awkward a thing, though, many smart people have spent years resisting the urge to think about these issues.

There’s a ~100% chance that someone will pop up in comments here and say “ah, just don’t look at that stuff, like I don’t!” And, indeed, with Twitter in 2024 in particular it very much feels easy to take that advice. After IFTTT integration was broken, myself and the guy who helped set up the previously-automated feed of posts here largely gave up on updating it, in part because “X” throttles Substack traffic so thoroughly that there’s no point. Even beyond that, though, the whole space now seems so fractured and chaotic that there’s little to be gained. Like I said, the “everybody in one room” internet had some advantages. But in the 2010s, in particular, many or most people involved in various cultural and political and creative fields felt that they simply could not have afforded to not be present on the network, and a lot of people who know these things will openly tell you that being considered funny on Twitter could get you a job at a lot of publications. Now, I think the profession is sort of trapped in this transitional stage, unable to let go of what Twitter was, casting around to see which of the many ballyhooed alternatives will take its place, and finding none of them particularly fulfilling. I hope nothing ever coalesces in that regard, but I don’t know what will happen. What I do know is that this industry was bent by the Web 2.0 experience in myriad ways, and the Elon Musk-assisted death of Twitter’s reputation has not unbent it. And that’s why “just don’t have an account” was never a real answer to the problem, if you were looking to make a living in these fields. Because the basic operation of the profession was changed by Twitter whether you yourself were on it or not.

One thing the massively-social internet has done has been to erase the line between drawing validation from a limited intentional community of peers and seeking that validation from everyone.

People like to say that the various follower/following systems on social networks and publishing platforms amount to smaller communities, like those tables in the high school cafeteria. But such walls are very porous, on the internet. (That which is digital is freely and endlessly replicable.) On Twitter, for example, any sense of privacy or quiet conversation engendered by the follower system could immediately be undermined by retweeting. Anything you said could be injected into the feeds of millions, as if someone in the cafeteria pulled out a megaphone and repeated something you said without warning or permission. This is what would happen when another inevitable pile-on came around, when seemingly the entire network would unite for days to excoriate a person who had said something the mob really didn’t like. The Justine Sacco mess, which no one defends directly but which many people excuse, set a template that every other user would recognize for the rest of their tenure on the platform. A Twitter mass shaming was the purest possible expression of the social pressure I’m talking about – someone would step out of line and be repeatedly, ritualistically scourged, with the various executioners often using the opportunity to show off their best material, joke-wise. That oftentimes the targets of these storms really had stepped out of line, in a genuinely ugly way, was no more an endorsement of that system of justice than a corrupt court arriving at the right verdict excuses the corruption.

Like I said, though, mostly the socialization process was less dramatic, slower, more incremental – everybody on my feed makes fun of this guy and lionizes that guy, and I want them to like me, particularly if I end up on the job market, and so I will fall into this same pattern. I don’t know how seriously to take simple behaviorist principles, at this point, but it seems uncontroversial to say that those behaviors which are rewarded will be repeated. And this all tended to come wrapped up with an illusion of independence, or an illusion of social approval of the independent. Because you could say anything on these networks, more or less, the fact that the actual conversation was so constrained by fear of losing the approval of one’s peers was less obvious. Han mentions the company Slack channel at Twitter, which is interesting in that Slack replicates many of the same problems but at least prevents the mass engagement that Web 2.0 services are based on. He writes

I joined the company almost a year after the January 6th reckoning, but the culture of open criticism was well preserved. On Slack, employees weren’t afraid to directly mention the company’s co-founder Jack Dorsey, or its C.E.O., Parag Agrawal; if someone poked fun at @jack or @paraga, the executives often responded with sassy repartee.

Well that’s lovely! But of course criticism on Slack can’t ever really be that open. You know that your peers and your boss and whoever else can see what you’re saying; if you say something really controversial, you could get canned, and even if your actual employer doesn’t punish you, all it takes is one screencap escaping into the wild to ruin your life. If you know the boss is on the conference call, it’s not a casual affair. I used to hate those professors who would go really hard on the whole “we’re all equals in this classroom” thing, for reasons explained in Zizek’s often-repeated story of the postmodern father: the denial of power relationships is always itself an expression of power relationships, and a notion of freedom that in fact reflects a subtler authoritarianism is more emotionally punishing to live under. “The apparent freedom of choice masks a much harsher choice.” I think this is just as true, or more true, when the boss or dad is distributed across a crowd. This is true of all of these networks; if you wish to make a living as a YouTube star, you would appear to have limitless freedom to create, and yet the influence of the algorithm and the audience and the ideology that is baked into the structure of the platform itself all press down on you and flatten the available means of expression. You are of course free to defy them, so long as you don’t get your video taken down. But such a choice almost always precludes the kind of mass success that makes a career possible.

The denial of power relationships is always itself an expression of power relationships, and a notion of freedom that in fact reflects a subtler authoritarianism is more emotionally punishing to live under.

Every crevice of the web (and increasingly our lives) is gamified. Dating apps have famously become sites of intense gamification and subject to the influence of various exploits, as people undertake a kind of amateur Big Data approach to affairs of the heart. Such behavior fundamentally stems from the understanding that the variation of human behavior and circumstance expressed in a given online system, while influential, is not necessarily more powerful than the ability to manipulate that system itself. You can make this more abstract or concrete as you like. Good luck making a living buying and reselling on eBay, which was once a viable path for most anyone who was willing to put in the work; the availability of so much information made it vastly harder to find opportunities for arbitrage. Airlines are starting to impose harsh new restrictions on their miles programs because people have so thoroughly optimized those systems. Tricks to finding a deal on an apartment online became too widely known and thus the comparative advantage was worn away. The concept of the sleeper in fantasy sports is now an anachronism, as the presence of such an immense amount of information means there are no more hidden gems to find. Car dealers expend immense effort and funds to prevent legal reform to the car-buying experience because they know that the internet’s price-discovery function would destroy their margins. Colleges now intentionally market to high school students they know will never earn an admissions spot, for the purpose of artificially lowering their admissions rate, which itself is an entirely fraudulent statistic that has no social value whatsoever.

My contention here today is that text-based personal expression networks like Twitter inevitably become subject to that same sort of gamification and algorithmic capture. People may not be A/B testing with the same dedication as a Twitch streamer, but they still put stuff out there, see what receives quantitative and qualitative approval through likes and engagement, and adjust their method. I suspect that some people do this consciously, but I’m even more confident that many people do it subconsciously. Silicon Valley has taken immense advantage of our status as creatures who are genetically engineered to be social; it just so happens that first agriculture and civilization, then digital technology allowed us to dramatically scale up how many people we were interacting with socially. (We quite literally weren’t built for this._ Opinion, personality, ideology – by the late 2010s, I would say, these too had become gamified, subject to exploits, wrung through the algorithm. And if I’m right about the ultimate origins of that malign influence, the fact that it was Twitter that became the most influential network for the hivemind of elite American opinion is just a trick of history. I am subject to claims that I have a negative obsession with Twitter, as well as various ironies and hypocrisies that stem from the fact that it’s me making the critique. But it could have been any number of other services that did the same thing; all it would have taken was an always-on network that rubbed people’s brains together 24/7. If Mastodon or Threads or whatever is the successor, the problem persists. And if short text networking dies, another kind could prove just as pernicious.

Han says that “Twitter’s laughably unserious name belied its seriousness.” I agree with that, but in a far darker sense than the one Han means.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.