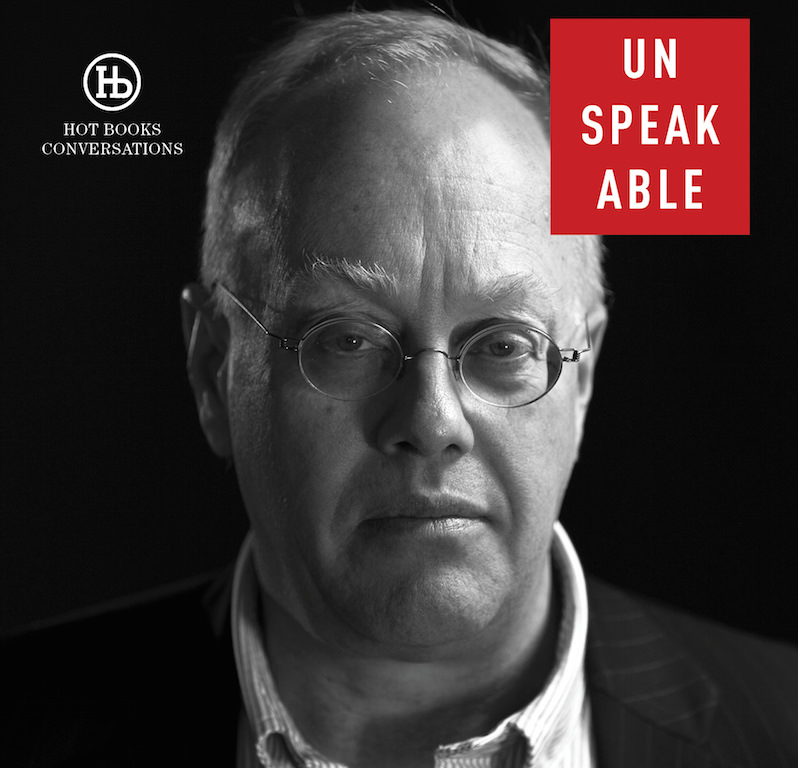

Chris Hedges Unmasks American Empire in ‘Unspeakable’

In this new book, the award-winning Truthdig columnist discusses taboo topics in America—including his experience as a radical war correspondent at The New York Times—with fellow journalist David Talbot.

Chris Hedges has been speaking truth to (and against) power since his earliest days as a radical journalist. (Skyhorse Publishing)

Editor’s note: The following excerpt is from “Unspeakable,” a new book by Chris Hedges and David Talbot. “Unspeakable” is published by Skyhorse Publishing. Click here for details.

The mainstream media reacted with shock at the rise of Donald Trump on the right, and Bernie Sanders on the left. Out of touch with the growing bitterness of America’s working poor, these families’ rage came as news to the journalists who dominate our national discourse. But Truthdig columnist and former New York Times reporter Chris Hedges has been shining a light on the most overlooked people and issues for nearly four decades. Now, he addresses these burning topics in a rare, extended conversation with fellow radical journalist David Talbot, founder of Salon and Hot Books.

Unspeakable

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Unspeakable

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Were you immediately made aware of the power that the Times gave you, as well as its limitations?

Yes. I didn’t abide by the pool system. I defied the rules. I went out alone. The other Times reporters were doing what Times reporters do best—sucking up to the authorities. They wrote a letter to the Times foreign editor saying I was destroying the paper’s relationship with the military. I knew the game. I was prepared to quit. I was young enough, I could go to another paper.

Why were the other reporters pissed off at you?

They were happily writing pool reports in the hotel. They didn’t want to go out. I blew their cover. If I could go out and get stories, why didn’t they go out? But [legendary Times editor and correspondent] R.W. Apple—Johnny Apple—was overseeing the paper’s coverage of the war from Saudi Arabia. When he found out about the letter, he called us all together. He said, “Look we don’t work for the military.” He was my great protector. He saved my job. They would have sent me back. Johnny made sure I could stay and report.

Johnny Apple famously broke the Times’ gray lady mold—he was flamboyant, full of himself, a well- known gourmand and dinner party host.

He had a lot of Falstaff in him. But he cared about the craft. He was an eloquent writer. He respected good reporters. He wasn’t going to let the institution destroy me. My colleagues at the Times, however, were only one of my problems. The more stories I wrote outside the pool system, the more the Bush administration wanted me silenced.

Dick Cheney—who was secretary of defense then, under George Bush I—demanded that about a dozen reporters who were defying the pool system be expelled. We were called “unilaterals,” a new name for our trade. I was high on the list. But they couldn’t find me. I was sleeping with Bedouins in the desert. The US military had already arrested me and confiscated my press credentials. But I did not use press credentials. I was there to be a reporter. If I couldn’t be a reporter, I would leave. I wasn’t going to sit in a hotel and write up press conferences and pool reports. At that point you might as well take a job with the Pentagon.

I entered Kuwait City before it was officially liberated. I drove my jeep while wearing a Marine Corps combat uniform down the six-lane highway leading out of Kuwait City as thousands of Iraqi soldiers in hundreds of vehicles were fleeing north to Iraq. This soon became the highway of death with miles of burned and wrecked vehicles and charred corpses. I was eventually taken prisoner by the Iraqi Republican Guard during the uprising in Basra after the war. I guess you could say I was embedded with the Iraqis.

And through all this, you managed to file some strong stories.

It was interesting—when I came back home after the Gulf War, even Abe Rosenthal, who was retired by then, told Joe Lelyveld, who replaced him as the Times executive editor, that he wanted to meet me. He came down to the newsroom to shake my hand and told me, “You’re a great reporter.”

So even Abe Rosenthal respected you as a war reporter. What did that feel like?

Rosenthal had the instincts of a good reporter. The problem was that, like many who rise within institutions, he cared more about his career than his integrity. He oversaw the publishing of the Pentagon Papers. We have to give him that. The publisher, Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger, who—to highlight how the close-knit fraternity of the elites function—went to my Connecticut prep school, was very reluctant. The idols of power, in the end, always atrophy your soul. Editors and the reporters, at least the ones determined to advance within the institution under Rosenthal’s eleven-year tenure as the paper’s executive editor, slavishly catered to his neocon ideology and numerous prejudices, including his blind support of Israel and virulent homophobia, which is why the paper ignored the AIDS epidemic. By the time Rosenthal retired and started writing a column, he was hysterical.

I’ll tell you what did mean something to me. When Homer Bigart [the Times’ widely respected correspondent who covered World War II as well as the wars in Korea and Vietnam] died around that time, Sidney Schanberg delivered one of the eulogies. He said we don’t have to worry, there are still reporters like Homer out there, and named me. Now that meant a lot to me. I didn’t care about meeting Abe Rosenthal. Bigart was a hero. He was a reporter’s reporter. He cared about the truth. He took tremendous risks to report it. He also loathed the paper’s hierarchy. He was once at his desk in the Times newsroom taking notes for a story about a riot that were being dictated to him by a reporter, John Kifner, from a pay phone. The riot was getting hot. Kifner finally told Bigart, ‘Jeez, Homer, I’m going to have to cut off because there’s like a hundred people that are going to push this phone booth over on me.” “At least you’re dealing with sane people,” Bigart answered.

So by the end of the Gulf War, you’re in pretty good standing in the Times newsroom.

Well, yes and no. Because remember, there were a lot of reporters who didn’t like me now. The New York Times is primarily populated by careerists. They do journalism on the side. The careerists always get you in the end.

These are the people who belong to the Council on Foreign Relations and will end up at the State Department or the Kennedy School at Harvard or on Wall Street?

Exactly. They are courtiers. They serve the elites. The elites reward them for their service with television appearances, lucrative book contracts, foundation grants, awards, journalism professorships and highly paid lecture fees. Many “prestigious” careers in journalism are built this way. These reporters spend their working lives as stenographers for the powerful. They are also your mortal enemy. They know you know them for what they are. Your reporting exposes them as mouthpieces for the elites. I had a few friends at the Times. I made the paper look good, so the hierarchy liked it, but I certainly had a lot of reporters who didn’t like me.

Still, you keep getting assignments overseas?

I was sent to Cairo as the Middle East bureau chief.

How old are you by then?

Early thirties…pretty young.

So if you wanted to play the New York Times game, you could’ve kept rising within that hierarchy?

Reporters like me do not advance at institutions like the Times.

Because?

As a war correspondent, I was paid to defy authority and often authority that was trying to kill me. War correspondents almost never reintegrate into newsrooms. We don’t bow easily before authority. At places like the Times you do not advance if you do not pay homage to the powerful and engage in the subtle games for patronage and influence. You have to be willing to incorporate the ideological parameters of the paper into your reporting.I spent my time in Central America with a backpack sleeping in mud and wattle huts. When I went to Israel, I was mostly in Gaza. I didn’t run off to see the Israeli foreign minister. When I covered the Gulf War, I rarely interviewed someone above the rank of lance corporal and slept in the desert. When I was in Bosnia, I traveled in my jeep from village to village or was in Sarajevo under the shelling and sniper fire. Interviewing those in authority was something I had to do as a Times correspondent, but I did it as little as possible. I never saw amplifying the lies of the powerful as an important or interesting part of my journalism.

So you didn’t play the game that most Middle East correspondents play. And playing the game was supporting the Israeli perspective if you were with the New York Times?

Yeah, [New York Times columnist] Thomas Friedman is the classic example of how to play the game. I think most of the other reporters there thought I was a bit insane. Clyde Haberman, the Times Jerusalem bureau chief, once said, “Hedges will parachute anywhere, with or without a parachute.” That was how they saw me. They were not wrong. I had too much of that hyper-masculine bravado that comes with being a war correspondent. I was also acerbic and blunt. This was not part of the paper’s culture.

I was covering the war in Yugoslavia. Roger Cohen [another marquee-name, roving correspondent for the Times] dropped into Sarajevo as soon as the ceasefire started.

He was based in Paris at the time. He had been my predecessor in the Balkans. He asked me what stories I’m working on, and I say, “I’m doing this and this and this and so on.” So then I go off into Bosnia somewhere, and while I’m gone, he stole my stories. He was gunning for a Pulitzer for his Balkans reporting.

He took what you had written?

No, I hadn’t written them yet. He took my story ideas and did them. We later had a dinner in Paris with all the Times foreign correspondents. Roger—who’s a snake—says to me in front of all the other foreign correspondents and the foreign editor, in this kind of saccharine voice, “Chris, I heard you’ve been saying things about me behind my back?” And, I said, “No, Roger, there’s nothing I’ve ever said behind your back I wouldn’t say to your face. You’re a shit.” You don’t do that at the Times. It shows a failure to exhibit the right decorum. At the Times you knifed your rivals or colleagues in the back, but you do it with finesse and cloying hypocrisy and…

A certain corporate gentility?

Yes. That’s it. The Times is a fear-ridden place. But it wasn’t fear-ridden for me. I didn’t care. I knew reporters who showed up for work and the first thing they did was go to the bathroom and throw up. It was an unhealthy place. These reporters and editors cared so much about having the “imprimatur” of the New York Times that the paper was able to carry out sustained forms of psychological abuse.

So, on the one hand, I protected myself because I didn’t play the game. On the other hand, it meant I was never going anywhere—in terms of rising within the hierarchy. Never. Those who rose in the paper had to prove over many years that they were pliant and obsequious to power. They had to endure this corporate hazing. They had to prove that the institution came before all else—including their own colleagues. They had to internalize the unwritten motto of the Times: Do not signifi- cantly alienate those on whom we depend for money and access. You can alienate them some of the time. But if you start to alienate them a lot of the time, your career is over. This unwritten mantra set vague, undefined boundaries that contributed to the deep anxiety that dominated the newsroom. Reporters had to intuit how far to go and intuit when to back off.

Those that persisted in reporting stories that made the elites uncomfortable, like Charlie LeDuff, who cared about the marginalized and the poor, who wanted to write about issues such as race and class, increasingly had to run into walls erected by the editors. You either conform or, as Charlie did, quit. The Times consciously caters to an audience of roughly 30 million people it has defined as the country’s economic and political elite. It does not care about the middle class. It does not care about the working class. And it certainly does not care about the poor. The bulk of the paper, with its special sections such as Styles or Home, addresses the concerns of the rich—maintaining a second house in the Hamptons. Those sections expose its bias.

Reporters who are too obtuse, or too stubborn, to conform become management headaches. If they persist, they are pushed out. This is why, I expect, most people at the Times are so unhappy. They have surrendered their independence and often their integrity. They are nervous about crossing the line that will see them singled out. It is a very hard high-wire walk they have to negotiate.

So the fear that gripped these men and women in the newsroom came from the fact they couldn’t see a life for themselves beyond the New York Times. It was the end-all and be-all?

Yes, it was just like Harvard. The attitude was not we are lucky to have you. It was you are lucky to be here. And since so many people at the Times had worked so hard to get there, they bought into this attitude.

And for you, you could imagine a life outside the Times.

Yes, I cared far more about what I covered. I wanted to make voices that were shut out heard. This pretty much guaranteed that I would have to eventually find a life outside the Times.

But there must have been occasions when you appreciated working for a newspaper with the power of the Times.

Of course—I used the power of the Times, but I didn’t allow the institution to own me. And that’s the tragedy of the paper. You have a lot of talent at the paper. But they are utterly deferential to authority. They invest tremendous energy into finding out what editors like them or whether their stock at the paper is going up or down. It’s a Byzantine court. I was the last person to hear the institutional gossip. It saved me from anxiety. But it also hurt my career. I didn’t know what was going on. I would get blindsided and not know it was coming.

When did the power of the Times help you as a reporter?

All the time. It opens a lot of doors. People return your calls. The institution is powerful enough to provide protection and the resources for protection. I had a $100,000 armored car in Bosnia and Kosovo, thousands of dollars of body armor, satellite phones, translators, drivers. Money was not an object. I walked around with thousands of dollars—in the former Yugoslavia the currency was German Deutschemarks—wrapped up in rubber bands in my pocket.When I was taken prisoner by the Iraqi Republican Guard in Basra, I disappeared. Although the Iraqis were holding me, they denied knowing what had happened to me. This, by the way, is very dangerous. It means that if you are too much baggage, you can be disposed of quickly, and no one is responsible. The Times got General [Norman] Schwarzkopf to call the head of the Iraqi army. They got [Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev to call Saddam Hussein. They even got the pope to call the foreign minister, Tariq Aziz, who was a member of the Chaldean Catholic minority in Iraq. Then, after I was released, the publisher had to pay the rental company $ 30,000 dollars for the jeep the Iraqis stole from me. I was in violation of the rental agreement.

You talked earlier about how you didn’t follow the pattern of Middle East bureau chiefs at the Times in how you covered Israel—can you explain that a bit more?

When I visited Israel [from the Times’ Cairo office], I lived in Gaza. In those days Gaza did not have a hotel. I lived in a run-down boarding house. Most reporters, especially Times reporters, didn’t want to go to Gaza. It was physically uncomfortable—I don’t know if it was that dangerous, but it wasn’t pleasant. The Times ran my stories almost always on the front page. They did not bury them. Most reporters drove down from Jerusalem, went through the Israeli checkpoint, stayed for a few hours to get the dateline and were home for dinner. They wrote canned stories, stories that had already been written in your head on the drive down from Jerusalem. This meant that the real stories rarely got out.

If the Israelis bombed Gaza, I’d go into the streets and count the bodies. The Israelis were furious. But what could they do? I was there. It blew a hole in the fiction they put out about surgical strikes.

So Israel’s official reports would minimize the casualties?

They lied. Constantly. They claimed not to target civilians while using their air force, tanks, naval gunships and heavy artillery to obliterate civilian neighborhoods. Their dishonesty is quite breathtaking.

When it comes to moments in your newspaper career like this, did you see yourself as more than a journalist—as someone, perhaps from your religious background, who was bearing witness?

Yes. I was clearly bearing witness. This is why I took the risks I took. But I also, like all good anarchists, distrusted all forms of power, even those that were ostensibly on the left or claimed to represent the oppressed.

I covered the war in Kosovo. I spent my time reporting on the suffering meted out to Kosovar Albanians by the Serbs. The moment the Serbs pulled out of Kosovo, I was reporting on the harassment and murder of the ethnic Serbian minority that remained behind. I never confused institutions or structures of power with the oppressed. I would never lie for a cause.

Journalistic objectivity is a fiction. I can take the same set of facts and spin a story to tell the truth or obscure the truth. Now if you’re a careerist, you’re going to spin the story in such a way that the power elites, both within the news institution and outside of it, are pleased. That is what they call balance. If you care about the truth, you are going to use those facts to convey the truth. That is what they call advocacy. And for them that is not a compliment.

Nonetheless, you’re saying that when it came to your coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, you were respected enough by your editors that the Times ran your stories on the front page—even though your stories ran counter to the Israeli, and perhaps the Washington, line?

That’s what often happens with a foreign bureau—you’re almost always in conflict with the powers back home, whether it’s the White House, the State Department, the Pentagon, the CIA or the Washington bureau of your newspaper. This became especially true when I covered Yugoslavia and [diplomat] Dick Holbrooke [who was in charge of President Clinton’s Balkans policy] tried to discredit everything I wrote. This made things difficult for me back home, because the Washington bureau is always going to give precedence to the official line. Editors and reporters based inside the Beltway are always doing lunch with the power elites. They depend on those lunches for their stories. And my reports from Bosnia—which after the war made clear the war criminals and warlords were still in charge—were irritating Holbrooke, who had invested his reputation in the Dayton peace agreement that ended the war. Holbrooke was the quintessential mandarin. He cultivated social ties with the powerful and the press, especially the hierarchy of the Times. He put a lot of energy into discrediting my reporting. I am sure he did damage.

So foreign correspondents like me can file their reports out of Gaza or wherever, but the preponderance of your newspaper’s foreign coverage is spewing out of official Washington. The paper gives a lot of play to what the Israelis want to be reported. The Israelis were always giving “intelligence briefings” to Judy Miller [the Times reporter who later became infamous for her false reporting on the Iraqi weapons of

mass destruction program]. These Israeli briefings saturated the paper.

The point is that, yes, the Times prominently played my reports from Gaza, but the weight of the [Israel-slanted] coverage was such that it kind of overwhelmed the reporting from the field.

Were you somewhat protected from Israeli pressure because you weren’t permanently based there?

Yes, I was based in Cairo. I was only in and out of Gaza. During my four years in Cairo, I spent maybe six or seven weeks a year in Gaza. If I had been in Gaza all the time, the Israelis would have pressured the paper to take me out. I was covering the whole region, including Iraq, Jordan, Turkey, Syria, the Gulf states and all of North Africa. So the Israeli government only had to put up with me a few weeks a year. But yeah, the Israelis and the Israeli lobby in the United States are powerful, deceitful and ruthless.

Who’s an example of a reporter who became an Israeli target?

Ayman Mohyeldin was pulled out of Gaza by NBC under heavy Israeli pressure. He had witnessed the Israeli military’s killing of four Palestinian boys on a beach in Gaza. There are many examples. The Israeli government is hypersensitive about anyone, including Israeli reporters, who challenge the official narrative. The Israeli reporters Gideon Levy and Amara Hass are routinely harassed by the Israeli government, have received death threats and are publicly vilified as accomplices of terrorists for writing the truth about the occupation.

By the time 9/11 occurs, you are finally back in the States. You were burning out by then as a war correspondent?

Yes. I had spent almost 20 years covering war. I was broken. I was a wreck.

Were you married at that point?

Yes, but you’re never home. My wife and two older children were overseas with me. We lived in Zagreb, or in Cairo—but I was rarely home. And when I did come home, I was exhausted and often sick.

This is your first wife, Josyane, with whom you had a son and daughter?

Yeah.

But you rarely saw your family?

Yeah.

How old were you by the time you came back to the U.S.?

Let’s see…early 40s.

So you knew you had to change your life.

I told the paper I had to stop. I wanted to take a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard, and the Times didn’t want to let me take it. The paper kept you on salary while you were at Harvard. Bill Kovach, who was the head of the Nieman program and had been the head of the Washington bureau at the Times, went to New York and met with Lelyveld and said, “Look, this guy has covered war after war for you. You’ve got to give this to him.” And Lelyveld hit the roof. I was on a satellite phone from Kosovo with my editor Andy Rosenthal, Abe’s son, who told me that Lelyveld had said, “All right, tell him he can take the Neiman and go to hell.” And Rosenthal told me, “I grew up at this paper—don’t do it because they are going to fuck you when you come back.” And I took it anyway, and went off to Harvard.Toward the end of my fellowship, I got a call from Lelyveld. He asked me what I was studying? And I said, “The classics.” And he said, “Like Latin?” and I said, “Exactly.”

There was a long silence and he said, “Well, I guess you can cover the Vatican.” I came back, and they fucked me, as Rosenthal warned. They wouldn’t give me an assignment.

Lelyveld was that vindictive?

They are all vindictive. They think they are infallible, like the pope. And there are no shortage of sycophants around them willing to feed their self-delusion. Lelyveld is, I will say in his defense, a fine writer, cares about good reporting and is literate. This is very rare at that level. His successors did a good job of removing all the gravitas, much of which he had promoted, from the paper. [Former Times executive editor] Bill Keller’s neocon trolls gutted the Book Review and the Week in Review. Lelyveld didn’t let the editors destroy my copy. He reached out to protect the handful of good writers at the Times—there aren’t that many there. He also hired me.

And, of course, you were known to be difficult.

I was difficult. I was hired to be difficult. I had been difficult in numerous war zones around the globe for two decades. That is how I did my job and got my stories. You can’t turn that off in a newsroom. When I returned from Harvard, it was like the old Soviet Union. You’re a member of the Politburo, and then one day you suddenly get sent to Kazakhstan. So I sat at home and read Dostoevsky. I can remember Lelyveld saw me in the newsroom after I had been called back and said, “You still remember how to write a story?” Stuff like that. I was on the “outs.” They wanted to make me do penance. It is like obedience training for a dog.

Because you were maybe a little abrasive? [smiles]

I was abrasive. Without question.

What year was this?

2000.

And then 9/11 happens.

Right. So 9/11 happens.

And by then Howell Raines has taken over from Lelyveld as executive editor.

Right. And I speak Arabic. So I’m assigned to the hijackers.

By the way, what was your relationship with Raines like?

Raines had no business running a newspaper. He and his managing editor, Gerald Boyd, were driven by naked ambition and self-promotion. This is not unique. But they were also insecure and incompetent. They promoted the con artist, Jason Blair, who fabricated and plagiarized stories. They empowered Judy Miller and Michael Gordon to publish the lies of the Bush administration to justify the Iraqi invasion. They pushed aside talented reporters and editors when they were not obsequious enough. It was all about who could grovel and flatter them the most. The newsroom, not made up of natural rebels, rose up in revolt. Raines and Boyd lost control of the paper,.

But before all that, you’re part of the team that covers 9/11?

Yeah, I reported from cities such as Paterson, New Jersey, where six of the hijackers had been living. Then I was sent to Paris to cover Al Qaeda in Europe and the Middle East.

And you’re finding out that the facts on the ground don’t go along with the emerging Bush-Cheney story line, that Saddam Hussein was behind 9/11.

The French government was apoplectic about the Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq. It made no sense to them. They knew Iraq had nothing to do with the attacks, that its army and military was severely degraded. Iraq was not a threat to its neighbors, much less to Europe and the United States. It did not have weapons of mass destruction. The French government, since I was with the Times, gave me carte blanche. I could go into the ministry of interior and ask for intelligence files. They were desperate to stop the war. It is a pity they failed.

They saw this train running out of control, driven by Cheney and his crowd.

Yes, and Al Qaeda was the problem, not Iraq. They had long experience with Islamic radicalism starting in the 1980s with the Paris Metro bombings by Algerian terrorists. I would come back to New York for meetings with the Times investigative unit. Judy Miller was part of that group. And the reporters and editors dismissed the French intelligence. They all drank the Kool-Aid. They were sure Lewis “Scooter” Libby—an Eaglebrook graduate, by the way—and the others in Cheney’s and Rumsfeld’s cabal were telling them the truth. The crazies were not only running the country but the coverage inside the paper.

You believe that Judy Miller, whose journalism career was eventually ruined, got scapegoated for spreading the WMD propaganda?

Yes, even though Judy Miller epitomizes everything I detest in reporters, but…

But she wasn’t the only one.

That’s right, it was an institutional failure at the Times. Howell Raines, and his successor Bill Keller and the investigative editors and reporters were all Bush’s useful idiots. It was a colossal journalistic failure—equaled by the paper’s cluelessness about the 2008 financial crash—that was dumped on Miller. They were all complicit.

Did any of your reporting that contradicted the Bush-Cheney line about Iraq get into the paper?

I was covering Al Qaeda. I wasn’t covering Iraq. I had one brief foray into that morass.

Yes, Judy Miller—in her own defense—later said, “Oh, even the great Chris Hedges got snookered by the Iraq story.”

Judy Miller and [investigative journalist] Lowell Bergman were working with Ahmed Chalabi [the Iraqi exile leader who was one of the principal sources behind the false WMD story]. Lowell was a producer at PBS’s Frontline. There was a joint project between the Times and Frontline. I was in Paris or somewhere in Europe. Lowell had set up an interview with what he said was an Iraqi defector in Lebanon—but he couldn’t go with his camera crew. The Times sent me. I didn’t vet the guy, I didn’t set up the interview. This often happens in big news organizations. You share reporting and information. I did the interview. It later turned out the guy’s story [about the Iraqi regime training Islamic terrorists] was bogus.So you too played your own small role in the Times’ disgraceful reporting during the runup to the Iraq War?

Yes. I have to take responsibility for it. It was my byline.

Did you ever talk to Bergman about it later?

No. I didn’t have an option to say no.

You’re part of an army.

Right.

But you had a history of questioning authority at the Times. Why not on this occasion? Did you get infected a bit by the post 9/11 madness?

I covered Iraq after the 1991 Gulf war. I reported on the destruction and dismantling by the U.N. inspection teams of Iraq’s chemical and biological weapons stockpiles. I knew Iraq’s nuclear weapons facilities had been destroyed by U.S. air strikes in the 1991 war. I knew that the Iraqi military machine, starved of funds and spare parts, was falling apart. But I also knew that Saddam Hussein had harbored various terrorists over the years including Abu Nidal. He had ties with Hamas. And he had held a series of meetings with Al Qaeda after his defeat in the 1991 Gulf War.

In 1992, when I was covering the Middle East, the Sudanese leader Hasan al-Turabi set up a meeting between the Iraqi intelligence and Osama bin Laden, who was living in Khartoum. Bin Laden requested the Iraqis provide weapons and training camps in Iraq. Ayman al- Zawahiri, at the time the ideological leader of Al Qaeda, traveled to Iraq that same year for a meeting with Saddam Hussein. He was there again in 1999 to attend the Ninth Islamic People’s Congress. He may have made other trips to Iraq. Iraqi intelligence, it appears from documents found after the 2003 invasion of Iraq in the archives of the Iraqi secret service, worked with Zawahiri and Al Qaeda to create the Kurdish Islamic militant group Ansar al-Islam, which was modeled on Hezbollah. Zawahiri, the current head of Al Qaeda, led the Al Qaeda insurgency against American forces inside Iraq after the 2003 invasion.

I did not see the invasion as justified. I believed the Bush administration was lying about weapons of mass destruction. But it was not beyond belief that Saddam was attempting to stoke terrorism against pro-western regimes in the Middle East and the United States by training and funding Islamic radicals, including Al Qaeda.

The two stories I published out of Beirut about Iraq’s supposed training of Islamic terrorists at an Iraqi military training center called Salman Pak, along with the alleged continued imprisonment in Iraq of about 80 Kuwaitis taken hostage during the first Gulf war, were, however, untrue. I went to Beirut with a healthy distrust of Saddam Hussein and, in retrospect, too much trust in the abilities of Lowell Bergman. I had asked U.S. Embassy officials in Ankara if the self-described defector was legitimate and was assured he was. But I should have done a more thorough vetting before I agreed to publish. I did not. This was my failure.

Of course when Bush finally invades Iraq in April 2003, you are a vocal critic of the war. When do you deliver the infamous speech about the Iraq War at the college commencement ceremony?

Spring of 2003.

And you’re still on staff at the Times, based in New York?

Yes.

And you’re invited by this liberal arts college in Illinois, Rockford College, to deliver the graduation speech. Did you have any connection to the school?

No. I knew that [social reformer] Jane Addams had graduated from there. The new president—who had written his doctoral dissertation on Addams—wanted to get somebody in the activist spirit of Jane Addams. I had breakfast with him at the college and said, “I’m going to be pretty harsh on the war” and he said, “Oh, not a problem.”

This was at a time when people like the Dixie Chicks were being banned from radio and Bill Maher was being fired from ABC for their critical comments about Bush and the war. And you step right into this fire and give a very powerful anti-war speech. And what was the reaction from the crowd that day?

It was not pleasant.

How many people were there?

About a thousand. They hated it. They booed and tried to shout me down…

And you could hear it loud and clear?

Yes. At one point they all got up and began singing God Bless America. They cut my microphone three times. Two young men from the graduating class got up in their robes tried to push me from the podium. I kept giving the speech. Michael Moore later saw a video of it and said, “I don’t know who the actor is in your family, you or your wife.” [Ed. Note: Hedges is married to actress Eunice Wong.]

So you kept bulldozing your way through all the sound and fury in the crowd?

Yeah.

And did you make it all the way to the end of your speech?

No, the president said I should, “Wrap it up!” after 18 minutes. Campus security escorted me off the stage before the awarding of diplomas. I was in an academic gown. I told them my coat was in the president’s office. They said, “We’ll mail you your coat”— which they did. They took me to my hotel room, waited as I packed my bags and drove me to the bus station. I got on a bus to Chicago.

So you escaped the tar and feathers. But you certainly felt the madness that was sweeping America in those days.

Yeah. The amateur video footage of the speech spread like wildfire. My daughter was in elementary school at the time, and they were watching some PBS show, and suddenly her whole class goes, “Hey look, that’s your dad!”

And what was the fallout at the Times?

The Times felt pressured to respond. The right-wing talk shows and cable shows lynched me hour after hour, day after day. The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial denouncing me. The Times issued me a written reprimand. Under Newspaper Guild rules, this the final step before being fired. Violate the reprimand, and you’re out.

What did they say was your violation?

I had impugned the impartiality of the paper.

By taking a strong stand against the war—a war which they had helped start, and which they later condemned?

Right. In contrast, [Times reporter] John Burns had taken a

stand supporting the war, but he didn’t get reprimanded. It wasn’t taking a strong stand that was the problem. It was taking a stand contrary to the dominant narrative.

And so you get this formal reprimand?

Right.

And then what happens?

I realize it’s terminal. It was not easy. I didn’t want to lose my job. But I was faced with a choice. I could muzzle myself in fealty to my career, but to do so would be to betray my father. I could not do that. When I left the building, I knew it was over. I also articulated for the first time what my father had given me—freedom. I did not need the Times or any institution to tell me who I was. I knew who I was. I was my father’s son.

I negotiated a fellowship with Hamilton Fish at The Nation Institute and left the paper.

So you quit—you didn’t get fired, as some believe.

I did not get fired, as [current New York Times executive editor] Dean Baquet reminded me the last time I saw him.

Do you think you would have been fired ultimately?

I’m not sure. I think many at the paper rolled their eyes and thought, “There he goes again.” I didn’t sense they wanted to lynch me. They were covering their asses. At the same time, I was often clueless about the internal politics. I could be wrong. Certainly, if there was another national incident like Rockford, they would have gotten rid of me.

I don’t have any animus toward the Times. I had a great run. They sent me all over the world. I am much, much happier writing books. I speak and write in my own voice.

Financially I have survived. I still read the paper.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, the New York Times-bestselling author of “Days of Destruction,” “Days of Revolt,” and “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning,” and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. He was a New York Times foreign correspondent for fifteen years, covering wars across the world. He currently lives in Princeton, N.J., with his family.

David Talbot is the author of the New York Times bestseller “Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years” and “The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government.” He is the founder and former editor in chief of Salon. He lives in San Francisco, Calif.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.