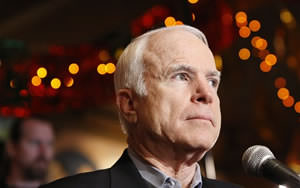

What John McCain Should Know

More than any other candidate for president, John McCain should know that peace talks can be stronger and smarter than bombs, that withdrawing American soldiers can be the best way to achieve stability, and that the best way to protect American troops is to bring them home from the war zone.

John McCain should know. More than any other candidate for president, John McCain should know that peace talks can be stronger and smarter than bombs, that withdrawing American soldiers can be the best way to achieve stability, and that the best way to protect American troops is to bring them home from the war zone.

John McCain should know, because he has lived this experience. After being held for nearly six years and tortured in a North Vietnamese prison, Lt. Cmdr. John McCain was freed — not by a daring commando raid on an enemy compound but by a negotiated settlement arrived at in peace talks in Paris. President Richard Nixon agreed to remove U.S. troops from Vietnam within 60 days, and the North Vietnamese government agreed to release American POWs like McCain as those troops were withdrawn.

John McCain should know that no one wins in the destruction of war. Even before he was shot down during a bombing run over Hanoi, the admiral’s son had questioned the human costs of armed conflict. In 1967, after McCain nearly died following a massive weapons malfunction and fire in the Gulf of Tonkin, the young Navy man told New York Times reporter R.W. Apple: “It’s a difficult thing to say. But now that I’ve seen what the bombs and the napalm did to the people on our ship, I’m not so sure that I want to drop any more of that stuff on North Vietnam.”

John McCain should know that yesterday’s enemy can be tomorrow’s ally and that alliances can be struck even after the United States is defeated on the field of battle. During the 1980s, McCain was one of the strongest advocates of establishing diplomatic relations with Communist Vietnam at a time when leaders of both political parties feared an angry backlash for simply talking to the other side.

In 1985, John McCain traveled to Hanoi to see Communist Vietnam for himself. He understood the value of putting the past behind him.

“When I arrived in Hanoi, I was excited to learn that my hosts had arranged for me a night’s rest at Ho [Chi Minh]’s villa in exotic Ha Long Bay,” McCain wrote in his 2002 memoir, “Worth Fighting For.” “As I … laid my head on the pillow in the bed, in the house where Ho had slept, I knew I had received all the recompense I was likely to get for the nights in Vietnam I had spent in less comfortable circumstances many years ago. There was nothing more I could gain revisiting the war with my former enemies. Better to enjoy the evening and in the morning see to more promising pursuits, among which was helping to build a relationship with Vietnam that would serve both our peoples better than the old one had.”

The John McCain of the 1980s and ’90s was a true warrior for peace. Working together with another Vietnam vet, Democrat John Kerry of Massachusetts, he helped disprove the saber rattlers’ contention that Hanoi still kept thousands of American POWs in secret camps. He did this by bridging the gap between high-ranking Pentagon and Communist officials, people who had been shooting at each other just a few years before.

In 1994 the Senate passed a resolution, sponsored by Sens. Kerry and McCain, that called for an end to a U.S. trade embargo against Vietnam. “The vote will give the president the kind of political cover he needs to lift the embargo, and I expect that relatively soon,” McCain told The New York Times. “I think it’s a seminal event in U.S.-Vietnamese relations.”

In 1995, when President Bill Clinton normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam, John McCain was in the room.

Where is that John McCain today? He now talks about keeping the U.S. in Iraq for 100 years and seems to have no conception of the hardship and pain American bombing raids have on the Iraqi people. Where is the maverick’s spirit of truth-telling when it comes to the lies the Bush administration told to get us into this war?

Today, McCain angrily calls out his Democratic rivals, arguing that they advocate an “arbitrary timetable” for withdrawal from Iraq “which recklessly ignores the profound human calamity and dire threats to our security that would ensue.”

John McCain should know better, because the history of the Vietnam War (and his involvement in it) shows that while peace takes time, it starts with the withdrawal of the U.S. military.

When the U.S. left Vietnam in 1975, the situation was indeed tragic; more than 400,000 people were rounded up by the victorious Communists and thrown into “re-education camps.” More than a million didn’t await that fate and fled by boat as refugees. The country’s economy remained a shambles and was isolated from the outside world. The same seems in store for Iraq when we leave.

But those setbacks were temporary and could not have been prevented by additional bombing runs or a “surge” of American troops. Indeed, the main thing that brought progress in Southeast Asia was the courage of people like John McCain — those who understood that America can achieve more through trade than it can through war and that tough diplomacy can achieve what a thousand bombing runs cannot.

Independent journalist Aaron Glantz has reported from both Iraq and Vietnam. He is author of the book “How America Lost Iraq” and runs the Web site www.warcomeshome.org.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.