The Surveillance State Is as Strong as Ever

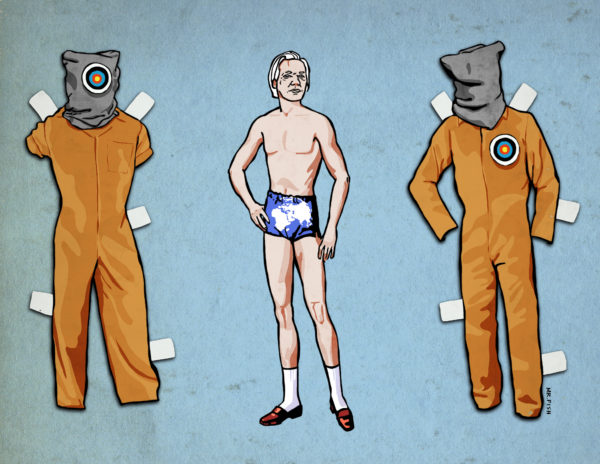

Don’t let the acquittal of Army Pfc Bradley Manning on aiding the enemy charges or the temporary asylum Russia granted to NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden fool you The harsh treatment of whistle-blowers will likely continue into the foreseeable future in pace with the needs and expansion of the surveillance state itself .

Don’t let the acquittal of Army Pfc. Bradley Manning on aiding the enemy charges or the temporary asylum Russia granted to NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden fool you. With American embassies and diplomatic missions on high alert across the Middle East and North Africa, the surveillance state remains as strong as ever, supported by leaders of both political parties and bolstered by a growing body of constitutional law crafted largely in secret by the federal court that oversees the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

This isn’t to minimize Manning’s limited victory or to underestimate the impact of Snowden’s efforts to avoid extradition. Under Section 104 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, aiding the enemy is the rough equivalent of treason (as defined in Article III of the Constitution). Like treason, it carries a potential death sentence, though in Manning’s case military prosecutors sought only a life term.

Still, Manning faces up to 136 years in prison after being convicted on 19 other charges, including six violations of the Espionage Act of 1917. In all likelihood, his sentence will be less than that, but he’ll still probably spend decades behind bars. A similar fate no doubt awaits Snowden should he one day fall out of favor with his Russian hosts and be returned to the U.S.

The harsh treatment of whistle-blowers will likely continue into the foreseeable future in pace with the needs and expansion of the surveillance state itself. In the aftermath of last month’s defeat of a proposed amendment to the Patriot Act that would have placed new limits on the National Security Agency’s ability to track phone records, there is little on the political horizon to halt the expansion.

Legally too the avenues for challenging the surveillance state are dwindling under the authority of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. Established in 1978, the court is a unique judicial body, consisting of 11 U.S. District Court judges appointed to serve staggered seven-year terms by the chief justice of the Supreme Court without Senate confirmation. All of the surveillance court’s current members were appointed by Chief Justice John Roberts. Ten are Republicans; nearly all have had legal experience working in the executive branch of the federal government or as prosecutors.

The FISA Court’s hearings are held in secret on an “ex parte” basis without notice to the targets of surveillance, and the tribunal’s orders are classified. Last year, the government filed 1,789 surveillance applications with the court. One application was subsequently withdrawn; all the others were granted, albeit with 40 modifications.

The government can appeal FISA Court decisions (in some instances, an Internet provider objecting to surveillance applications can too) to the FISA Court of Review, a three-judge panel similarly appointed by the chief justice. The Court of Review also conducts its proceedings in secret and has sole discretion to release its rulings to the public. Its decisions can be appealed only to the Supreme Court. None of them, however, have been appealed thus far.

Although the FISA Court and the Court of Review reportedly have prepared more than a dozen substantive rulings over the years, until last week only two highly redacted opinions had been publicly released, both by the Court of Review — In re: Sealed Case, found in the official reports of federal appellate court decisions at 310 F.3d 717 (2002), and In re: Directives, found at 551 F.3d 1004 (2008).

Taken together, the two decisions uphold FISA’s constitutionality and recognize a constitutional doctrine not yet decided on by the Supreme Court — that there is a “foreign intelligence” exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement. The Directives case, which technically dealt with the Protect America Act that was later repealed and replaced by the FISA Amendment Act of 2008, went even further. It held that notwithstanding a formal foreign intelligence exception to the Fourth Amendment, NSA’s spying operations are constitutionally permissible under a variety of so-called “special needs” cases decided by the Supreme Court that have authorized drug and alcohol testing on high-school students and railroad workers without warrants or probable cause.

Last week, in a clumsy attempt to allay growing public skepticism about its spying operations, the Obama administration declassified a redacted version of the FISA Court decision that approved the now-infamous order issued last April directing Verizon Business Services to turn over bulk records of all phone calls made inside the U.S. and between the U.S. and abroad to the FBI. The administration also declassified Justice Department legal memos from 2009 and 2011 on the legality of phone record collection.

Contrary to the administration’s hopes, the released material is anything but encouraging. The decision — written by former FISA Court Judge Roger Vinson, a senior federal District Court judge from Florida who gained notoriety in 2011 for declaring the entire Affordable Care Act unconstitutional — sheds no light on why the bulk collection order issued to Verizon, and presumably duplicated in orders served on other phone companies, was needed to further specific investigations into international terrorism. And the analyses only underscore the questionable legal reasoning previously adopted in the Sealed and Directives cases.

In the meantime, according to Edward Snowden, as reported by journalist Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian, the NSA’s spying techniques have become ever more sophisticated with the implementation of the XKeyscore program, enabling agency analysts to search without prior authorization through vast databases containing emails, online chats and the browsing histories of millions of individuals.

In another era, the Supreme Court might have been expected to intervene in the controversy and restore a sensible constitutional balance between the nation’s legitimate need for security and the right of its citizens to privacy under the Fourth Amendment. But this isn’t another era. Just last term, in a 5-4 majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito, the high court dismissed a FISA challenge brought by Amnesty International and other human rights groups in the case Clapper v. Amnesty International, reasoning that none of the organizations had suffered actual legal harm, and thus lacked “standing” to sue.

Whether the present Supreme Court would intervene on the side of privacy were it disposed to get involved is dubious, of course. But one thing remains certain: Unless and until the high court gets involved, our Fourth Amendment rights will continue to be shaped by another court that meets behind locked doors and publishes its rulings only when it sees fit.

So whistle-blowers and everyone else take heed, and welcome to the new era. It looks like it’s here to stay.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.