What’s Next for Julian Assange

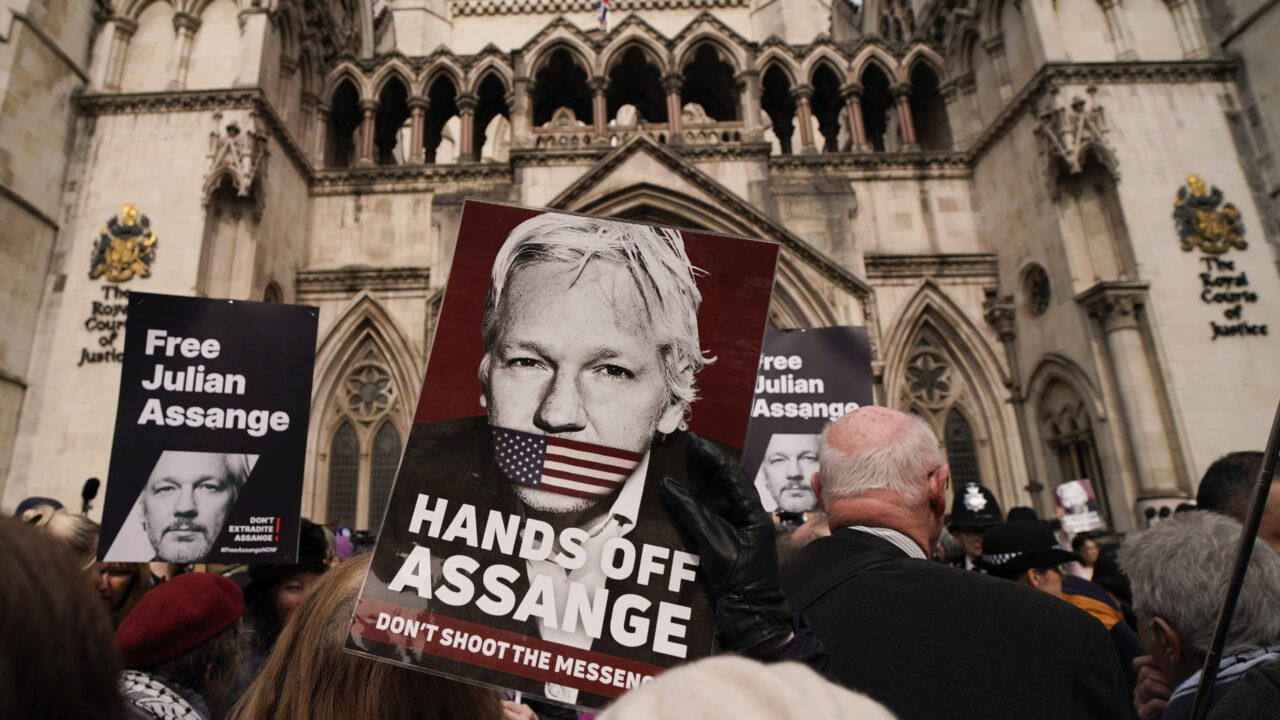

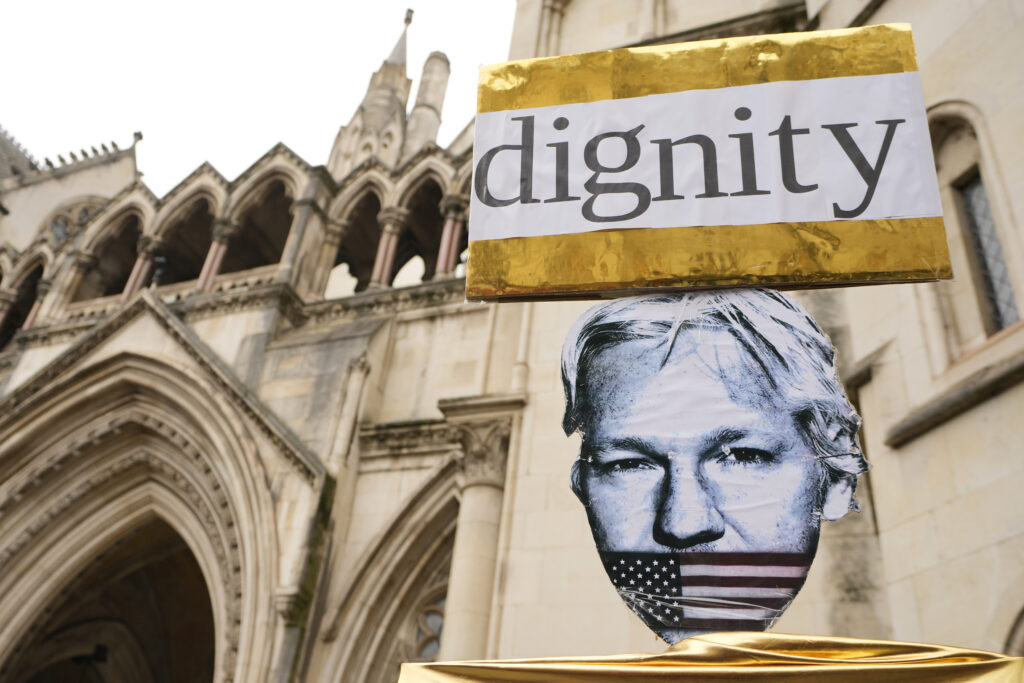

The WikiLeaks founder will get a chance to appeal extradition if assurances aren't made. Demonstrators hold placards after Stella Assange, wife of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, released a statement outside the Royal Courts of Justice, in London, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. Two High Court judges said they would grant Assange a new appeal unless U.S. authorities give further assurances about what will happen to him. The case has been adjourned until May 20. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali)

This is Part III of the "The Persecution of Julian Assange" Dig series

Demonstrators hold placards after Stella Assange, wife of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, released a statement outside the Royal Courts of Justice, in London, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. Two High Court judges said they would grant Assange a new appeal unless U.S. authorities give further assurances about what will happen to him. The case has been adjourned until May 20. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali)

This is Part III of the "The Persecution of Julian Assange" Dig series

UPDATE: On Tuesday, March 26, the High Court in London issued a delay in the extradition saga of Julian Assange. It has given the United States government three weeks to provide assurances that Assange would be granted a fair trial, with full Constitutional rights as a foreign citizen and not face the death penalty. If the United States does not satisfy the Court’s concerns, it appears that the Court will grant Assange a full hearing to appeal his extradition to the U.S., where the WikiLeaks founder would face trial in a federal courtroom on charges totaling a possible 175 years in prison.

LONDON — The hearings on Julian Assange’s appeal request ended yesterday, as expected, without closure. “We will reserve our decision,” said one of the two presiding judges. The choice to delay an announcement may have been influenced by the presence of several hundred Assange supporters gathered at the heavily policed entrance of the neo-Gothic Royal Courts building in Westminster.

A cold drizzle had thinned the previous day’s crowd of a thousand or more, but not by much. The lawyers arguing the U.S. government’s extradition request had to exit the court under escort through the chants and jeers, eyes straight ahead, pretending not to see the placards with Assange’s face next to sentences like JOURNALISM VS. WAR CRIMES: DON’T LET THE WAR CRIMES WIN and R.I.P. BRITISH JUSTICE: 1215 — 2012.

If the court has decided to deny Assange’s request for a full appeal, there was good reason to delay the announcement until after the chartered buses returned the protestors to their hometowns and the international media — which filled three spillover rooms inside the court and clogged the median on Fleet Street with tripods — moved on to the next story.

When announced, the decision will end another chapter in a legal saga that began in 2012, when Assange entered Ecuador’s London embassy to avoid extradition to the U.S. or Sweden, where he was the subject of a sexual assault investigation that was later dropped. If the judges decide to buck Britain’s political establishment and approve Assange’s appeal request, the WikiLeaks founder will remain in Belmarsh prison while his lawyers challenge the government’s extradition order, issued in 2022 after the High Court ruled Washington’s request valid under the terms of the Anglo-American Extradition Treaty. If they deny Assange’s request to appeal, it will mark the end of the road in His Majesty’s Courts. The last recourse will be an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, to which England belongs.

In theory, that court has the authority to stay and reverse the extradition. It’s possible, too, that the British will not wait for this to take place before handing Assange over to U.S. marshals, who are currently in London awaiting the first opportunity to escort him to a federal court in northern Virginia. There, he faces 175 years in prison on charges of one count of hacking and 17 counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917.

The hearings that concluded yesterday offered a preview of a full appeal. On Tuesday, Assange’s team had one day to argue against the High Court’s previous greenlighting of the extradition; on Wednesday, lawyers for the U.S. government defended the ruling. Much of the argument revolved around competing interpretations of the U.S.-U.K. Extradition Treaty, in particular a series of treaty revisions passed by Parliament in 2003.

Assange’s lead lawyer is a human rights attorney with a specialty in extradition cases named Edward Fitzgerald. For much of the six hours allotted to his team, he argued that previous rulings had failed to account for the treaty’s “political offense” exception that states “extradition shall not be granted if the offence for which extradition is requested is a political offence.”

WikiLeaks’ exposure of U.S. war crimes not only put Assange beyond the reach of the Extradition Treaty, he argued, they obligated Britain to investigate those crimes.

Citing testimony given by Daniel Ellsberg and Noam Chomsky in previous hearings, Fitzgerald described Assange’s political motivations and quoted the U.S. government’s own language to show how the indictments reflect a “quintessentially political offense” and thus extradition “should not be sought or granted.” He also cited other treaty language and international legal regimes to which Britain is party. The Refugee Convention, for example, states that the exposure of endemic state criminality is inherently political. News reports that the CIA and the White House in 2017 discussed plans to kidnap, rendition or poison Assange inside the Ecuadorian embassy, Fitzgerald told the court, obliterates all doubt that the U.S. case against Assange “is a paradigmatic example of state retaliation for expression of political opinion.”

Fitzgerald went further. WikiLeaks’ exposure of U.S. war crimes not only put Assange beyond the reach of the Extradition Treaty, he argued, they obligated Britain to investigate those crimes. Citing domestic criminal law and international treaties, including the Geneva Convention, Assange’s lawyers returned accusations of criminality to the U.S. and British governments. “It is the right, and indeed the duty of every U.K. resident (as Mr Assange was at the time of these publications) to assist the U.K. authorities to fulfill these duties to investigate, prevent and (where appropriate) prosecute crimes of universal jurisdiction,” states the 150-page grounds for appeal.

All of this, crucially, was omitted in a 2021 ruling by a District Court judge that blocked the extradition on the narrow humanitarian grounds that Assange was likely to kill himself if faced with a lifetime in solitary confinement.

The next morning, a former public prosecutor named Clair Dobbins delivered the U.S. government’s case for upholding the prior extradition ruling without further delay. Like Fitzgerald, she spent much of her time in the weeds of the political offence exception. Years before it was formally superseded by the 2003 Treaty Act, she argued, it was in gradual decline, and by 1996 was seen as a Cold War-era anachronism, a relic of an era “when political persecution was visible in primary colors.” Excusing Assange, she suggested, would be akin to freeing a “terrorist” who justified his acts by pointing to the “political opinions” that inspired them.

The comparison, of course, was a tortuous one, given that Assange revealed lawless violence on the part of the U.S. government, not the other way around. But a defining feature of Assange’s nine-year legal saga has been an absence of attention to the crimes he exposed, and yesterday was no different. Dobbins maintained that the U.S. indictments targeted criminal behavior that harmed U.S. national security and the lives of a global network of U.S. collaborators and informants.

The comparison, of course, was a tortuous one, given that Assange revealed lawless violence on the part of the U.S. government, not the other way around.

Although the hacking charge against Assange is just one of 18, Dobbins spent significant time asserting that Assange was a central, active agent in Chelsea Manning’s theft of government data. Assange, she said, was “a party to hacking, not a recipient [who] set up an online box.” Her evidence on this front was a thin gruel familiar to anyone who has been following Assange’s case over the years.

She cited Assange’s cryptic comment to Manning in 2010 that “curious eyes never run dry” as proof that he was the puppet-master overseeing the massive military and diplomatic leaks that put WikiLeaks on the map. She also made much of Assange’s offhand comment during a public talk that Americans should join the CIA to expose its crimes. Proving that she has not read “All the President’s Men,” she argued that Assange’s “contact with Manning over many months” separates him from a “typical investigative journalist.” She also emphasized the point of Assange’s decision — questioned at the time by some Assange supporters and journalistic partners — to release the classified documents with names unredacted. But as even Pentagon prosecutors conceded during the Manning trial, there is no evidence that anyone working with the U.S. government suffered physical harm as a result of WikiLeaks’ unredacted document dumps. The U.S. again recognized a lack of such evidence during the extradition hearings of February 2020.

In one of the hearings’ stranger moments, Dobbins cited WikiLeaks’ “chilling effect” on the willingness of people around the world to provide information — including, presumably, highly classified information — to the U.S. government. In a quiet voice that may have betrayed a flicker of self-awareness, Dobbins spoke of “broader consequences on the ability [of the U.S.] to gather information from… people willing to come forward [and work with the U.S. military and spy agencies.]”

If these arguments weren’t enough to uphold the extradition order, Dobbins appealed to the “special relationship” that has long bound the U.S. and British national security establishments. Above and beyond the debatable specifics of national extradition law, she reasoned, is a well-established “fundamental assumption” by the British government “of good faith by long-standing partners.” The U.S., in other words, can be trusted to do the right thing for the right reasons. At least one of the two presiding judges, Jeremy Johnson, has a history that would seem to predispose him to this argument, including extensive prior experience representing the Ministry of Defense and MI6. But even Johnson seemed taken aback by the U.S. government’s claim that Assange would not enjoy First Amendment protections in court as a foreign citizen.

Dobbins did say one thing everybody can agree on. “Though the U.S. administration has changed,” she informed the court, “the prosecution [of Assange] remains very firmly on foot.” Indeed, the charges initially unsealed in 2019 and 2020 by Trump’s second attorney general, Bill Barr, have been vigorously upheld and may very well culminate under Merrick Garland.

Though hard to imagine now, there was a time when U.S. charges against Assange from both presidents seemed unlikely. During the 2016 campaign, Donald Trump famously declared his “love” for WikiLeaks following its publication of nearly 20,000 emails by Democratic National Committee officials. This changed two months into Trump’s term, when Assange published the first tranche of “Vault 7,” a staggering collection of documents that detailed the CIA’s use of eavesdropping technologies, including malware that allowed the agency to spy on people through “smart” appliances like televisions and refrigerators even when they were turned off. Weeks after the first release of classified documents, Trump’s CIA director, Mike Pompeo, ominously told a public audience that WikiLeaks should be viewed as a “non-state hostile intelligence service.” Soon Pompeo would be conferring with the White House about “options” for Assange’s rendition and possible assassination at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where the agency began to spy on Assange’s visitors.

Publicly, the Trump administration appeared to move more slowly. It announced its first indictment against Assange in April of 2019. This consisted of a single charge of hacking conspiracy based on the allegation that he helped Manning crack an encrypted government network. When the newly elected president of Ecuador, Lenin Moreno, revoked Assange’s asylum and handed him over to British police, he was taken to the maximum-security Belmarsh prison. He was there a little more than one year when U.S. prosecutors unveiled a second, superseding indictment containing 17 charges of violating the Espionage Act of 1917. All pertained to the military and diplomatic leaks of 2010-2013. In content and structure, they resembled cut-and-pastes from the military trial of Bradley Manning four years earlier.

By the time Joe Biden assumed office in January 2021, Assange’s health was rapidly declining after nearly four years in Belmarsh. Any hope that the new president would drop the case was soon dashed. A month into Biden’s term, the U.S. sought and won an overturning of the lower court’s block of the extradition on humanitarian grounds. Thanks to the British journalist James Ball, we know that the Biden Justice Department has also used “vague threats and pressure tactics” to coerce British journalists to help in its extradition campaign.

A month into Biden’s term, the U.S. sought and won an overturning of the lower court’s block of the extradition on humanitarian grounds.

This was a striking turn by the Democratic president. For eight years, Biden served a president who understood the First Amendment protected Assange from indictment under the Espionage Act. Not that the Obama administration didn’t think about using the Espionage Act, and even long for it. As early as 2010, Attorney General Eric Holder had called for “an active, ongoing criminal investigation” of WikiLeaks using the provisions of the 1917 law.

But as with preceding administrations going back to Richard Nixon — who contemplated using the Espionage Act to indict The New York Times for publishing the Pentagon Papers — the Obama Justice Department chose to honor the sacrosanctity of the reporter-source distinction. The alternative was messy attrition that would look a lot like a war on the free press. To its credit, the Obama administration held the line even after the publication of Edward Snowden’s revelations regarding mass state surveillance in 2013 and WikiLeaks’ release of DNC emails in 2016.

Obama instead chose a different path. In the 40 years since Daniel Ellsberg faced Espionage Act charges for the Pentagon Papers — the closest analogue to WikiLeaks’ Iraq and Afghanistan war logs — the law had been reserved for U.S. citizens spying on behalf of official enemies. This changed under Obama’s Justice Department, which famously levied eight Espionage Act cases against leakers who disclosed details about the dark side of the war on terror. The longest of their sentences contrast tellingly with the 175 years facing Assange. Until last month’s sentencing of Joshua Schulte, the CIA agent who received 40 years for leaking Vault 7 documents to WikiLeaks, the longest prison term served by a government leaker was the security contractor Reality Winner, who did five years at a minimum security prison in Fort Worth. (For endangering covert agents by sharing his notebooks full of classified information with a biographer, former CIA director David Petraeus received two years probation and a token fine.)

The logic that kept the Obama administration on constitutional rails — even when it was most tempted to establish the dangerous precedent set by Trump — was spelled out in a 2011 Washington Post op-ed by Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard Law School professor and assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush Justice Department. Distinguishing between WikiLeaks and the Post was difficult, if not impossible, Goldsmith observed, because

national security reporters for The Post solicit and receive classified information regularly. And The Post regularly publishes it. The Obama administration has suggested it can prosecute Assange without impinging on press freedoms by charging him not with publishing classified information but with conspiring with Bradley Manning, the alleged government leaker, to steal and share the information. News reports suggest that this theory is falling apart because the government cannot find evidence that Assange induced Bradley to leak. Even if it could, such evidence would not distinguish the many American journalists who actively aid leakers of classified information.

Goldsmith’s words are as true today as the day they were published.

If the High Court upholds the 2021 extradition approval, Assange’s last hope is an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, an international court overseen by the Council of Europe. Britain is a party to the Council’s European Convention on Human Rights, and thus would be obligated to respect an ECHR judgment blocking the extradition order. If the Court were to rule in favor of Assange’s appeal, the British foreign secretary would then have to decide whether to follow it, or buck an institution that is broadly representative of continental political opinion.

“A huge majority in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has called for the immediate release of Julian Assange,” said Andrej Hunko, a member of German Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. “This is a very good sign for the future of press freedom and suggests a possible intervention by the Strasbourg Court — one that I would expect the British authorities to respect.”

If this comes to pass, it would involve an ECHR instrument known as a Rule 39 instruction, which allows the ECHR to supersede national justice systems. Whether the British authorities would flout this authority before the eyes of the world is unknown, but there is little question that the details of Assange’s case contain multiple violations of the European Charter, including its prohibition of extradition in cases where the law “crosses a new legal frontier” — in Assange’s case, the application of the Espionage Act to publishers — as well as statutes related to free speech, abuse of process and the right to a fair trial.

If the Human Rights Court declines to take up the appeal, or if Britain refuses to honor its obligations — possibly by handing over Assange before the ECHR can issue an injunction — the next and likely final chapter of Assange’s legal saga would be a jury trial of the kind he was denied in Britain. But across the pond, the advantage of a jury trial would vanish. This is because the trial would be held at the U.S. District Court in Alexandria, Virginia, where jurors are drawn from zip codes full of government employees, defense contractors and their families. “Lots of whistleblowers have been tried and convicted in that court,” says Stephen Rohde, who practiced First Amendment law for almost 50 years and has written extensively on the Assange case. “It’s a setup for conviction.” Given this reality, Assange’s lead U.S. attorney, the noted Washington criminal lawyer Barry Pollack, would seek an early motion to dismiss, and pray the case is overseen by an aggressively pro-constitution judge with an independent streak.

A conviction in Virginia would almost certainly amount to the death sentence predicted by the British District Judge in 2021. Assange, 51, was not well enough to appear in person or remotely at this week’s hearings. As his brother explained this week, “He’s going through an immense amount of suffering. He’s deteriorating. His health is in a very delicate position.”

If Assange dies in a U.S. prison, much will die with him. It will mark the first time that a publisher or journalist has been prosecuted under the Espionage Act, the remaining appendage of the original Espionage and Sedition Acts (1918 – 1920) that defined treason down to include advocating leftist political ideas and were used to monitor the mail of American citizens for “suspicious” ideas and beliefs. Paired with the Immigration Act of 1918, which allowed for the arrest and expulsion of perceived “subversives,” the law was used by the newly formed FBI to conduct 3,000 mostly warrant-free arrests. If not for a brave intervention by Wilson’s Labor Secretary, most of them would have been forcibly deported.

This lineage is not incidental to the looming prospect of the law being used to sentence the publisher of state secrets. Doing so will set a monumental precedent and set the stage for what press freedom advocates promise will be more sweeping prosecutions of journalists and acts of journalism in the future. James Goodale, who led The New York Times’ Pentagon Papers defense, recently told former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger, “If the prosecution succeeds, investigative reporting based on classified information will be given a near death blow.”

If Assange dies in a U.S. prison, much will die with him.

The global implications were made clear in the network of journalists that have rallied in international solidarity behind Assange’s cause. “I brought a banner of 40 trade unions from Peru to Indonesia, from the U.S. to India, all of them demanding Julian’s freedom,” Tim Dawson, a London Times veteran serving as deputy general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists, told me while standing in the rain on Wednesday afternoon. “Why would journalists all over the world express concern about a case in a British court brought by the United States? Because the actions Julian Assange undertook are actions journalists take every day. Finding confidential sources, encouraging them to share information. Be under no illusions, if this is successful, vital cases will not come to light. Journalists the world over will be afraid to do the same. There are more of us out here than during the last hearing. People are starting to understand what is at stake.”

Despite occasional signs of life, the U.S. establishment media does not appear to understand these stakes; and if it does, it is timid about trumpeting them with the urgency they deserve. In November 2022, The New York Times published an open letter — co-signed by The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel and El País — recommending the U.S. government drop its charges against Assange and avoid setting “a dangerous precedent” that “threatens to undermine America’s First Amendment and the freedom of the press.” The Times’ institutional voice was absent this week, however, as the paper settled for an opinion column by Jamie Kirchick that came down against extradition only after hundreds of words explaining his disdain for Assange “as a man unhealthily preoccupied with the shortcomings of democracies.” This was more than The Washington Post could muster. In a 2019 editorial, two years after adopting the tagline “democracy dies in darkness,” the paper claimed that Assange was “not a real journalist” and that his extradition posed no threat to freedom of the press.

It was a sign of lukewarm interest in Assange’s case that many of the pieces published about this week’s hearings centered on a publicity stunt organized by Andrei Molodkin, a Russian émigré artist based in southern France. Molodkin has collected 16 donated artworks by Warhol, Rembrandt, Picasso and others inside an iron safe containing a bomb rigged to release a corrosive material in the event that Assange dies in prison. “Without freedom, journalism and art is propaganda,” Molodkin told me on the eve of the London hearings. “I don’t see a future for journalists or artists if he is allowed to die in prison.”

If Assange is freed, Molodkin plans to exhibit the 16 works in museums around the world as a symbol of freedom. If Assange is sent to a maximum-security prison to waste away, the artist will flip the Dead Man’s Switch on the safe and reduce the masterworks to dust. Molodkin is hopeful that this second scenario will not come to pass, but if it does, he will exhibit the paintings in their new form, as a bowl of white ash. He says the museum label above the ashes will list his name as the second of two collaborating artists.

The first will be the United States Government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.