Why Russia Just Can’t Quit Syria’s Dictator

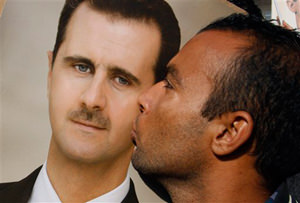

The Kremlin risks international isolation with its uncompromising stance on Syria, but Russia has powerful incentives to protect Bashar al-Assad.

The violence in Syria shows no signs of abating and the country is quickly sliding into civil war. This week, the battles between government troops and the armed opposition reached the suburbs of Damascus. To date, more than 5,000 people have died in Syria, most of them civilians. The observers’ mission of the Arab League has failed to stop the violence, and its members are split over what to do next. In the U.N. Security Council, Russia and China have blocked any Western attempts to internationalize the conflict or even to condemn the Syrian leadership for its violence against protesters.

Russia has been a particularly steadfast supporter of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government. Its opposition to stronger actions against the Syrian regime is founded in a fundamental aversion to revolutionary change and strong economic and geopolitical interests in the country.

The main goal of Russia’s Syrian policy is to avoid a second Libyan scenario. In that nation, the Russian government was split between a policy of noninterference and support for, or at least toleration of, NATO’s military intervention on behalf of the rebels. The latter position won out when Russia decided not to use its veto to block the U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973. With regard to Syria, however, the policy of nonintervention has so far prevailed. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs made it clear in December 2011 that it opposed any kind of foreign intervention and trusts that “Syrians should reach an understanding” by way of “national dialogue between the authorities and the opposition.”

The Foreign Ministry emphasized in November that it considered “the maintenance of the unity, territorial integrity and sovereignty of Syria as one of the key countries in the Middle East” to be the primary task of the international community. Faced with growing criticism of its position and calls for Arab League troops in Syria, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov went even further. In mid-January, he warned that the policies of the West and the Arab League could lead to “a very big war that will cause suffering not only to countries in the region but also to states far beyond its boundaries.” For Lavrov, the opposition forces in Syria are nothing but “militants and extremists.” He quoted the recent terrorist attacks in Syrian cities as proof of this claim.

Lavrov’s attitude primarily reflects Russian cynicism about the results of the so-called Arab Spring. Where others find liberation in the Arab world, most pundits in Russia see the spread of extremism and instability. “The Arab revolutions of 2011 have produced the rise of fundamentalist extremism and civil wars, which may expand to become overt religious warfare with dire challenges to the global community. The expectation for democratization of dictatorial regimes in the region is sentimental and self-delusional,” writes Vladimir Belaeff, head of the Global Society Institute, in Russia Profile.

This kind of instability gives rise to fears that uprisings in the Middle East will affect Russia’s own restive Caucasus region. Observers compare the Caucasian republic of Dagestan to Syria because of its similar web of ethnic and religious tensions and conflicting loyalties. The Russian government is particularly worried that a civil war in Syria would strengthen Islamic insurgents in the Caucasus. The Arab Spring, in combination with the recent U.S.-Iranian tensions, have even led the Kremlin to order the Russian military to prepare for a potential spillover of hostilities into the Caucasus.

Russia’s concern for regional stability is, however, only one reason behind its support for the Syrian regime. Business interests are almost equally important. In the last six years, Russia has invested heavily in Syria. In 2009 alone, investments in Syrian infrastructure, energy and tourism amounted to $19.4 billion. Russian companies such as Stroytransgaz and Tatneft are spending billions to develop Syrian natural gas and oil resources.

In 2005, Russia also forgave Syria three-quarters of its Soviet-era debt — almost $10 billion. President Dmitry Medvedev’s visit to Damascus in 2010 resulted in a series of economic and military agreements. A new regime in Syria could jeopardize all of those deals. Russian fears are once more based on the Libyan case: It is doubtful whether the new government in Tripoli will honor the approximately $10 billion in contracts between the Gadhafi regime and Russia.

Syria is also a valued customer of Russia’s struggling arms industry. Current arms contracts between the two countries are estimated at $4 billion. In December, they signed an agreement for the sale of 36 Russian fighter planes, valued at $550 million. That deal, along with alleged Russian ammunition shipments in January, is undermining any international attempt at establishing an arms embargo against the repressive Syrian regime.

Russia appears unwilling to abandon its decade long economic and military cooperation with Syria. The Soviet Union and Syria established diplomatic ties in the first days of the Middle Eastern country’s independence from France in 1946. Soviet specialists built the lion’s share of the Syrian rail and oil production infrastructure. Syria was one of the only countries that supported the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan in 1979. In return, the USSR provided Syria with generous military and economic support. Nine-tenths of the Syrian army’s weapons were produced in the Soviet Union. Last, but not least, the Soviet navy established a base in the Syrian port of Tartus in 1980, its only naval base in the Mediterranean. Russian specialists are renovating the base as part of the Russian navy’s efforts to strengthen its presence in the Mediterranean. A pro-Western government in Syria or the country’s fragmentation in a civil war would threaten this important foothold in the region.Russia is willing to play a big gamble to assert its interests. In response to the appearance of American warships off the coast of Syria, Russia dispatched a flotilla under the aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov to Tartus, which the Syrian government received with military honors in January. This demonstration of military strength shows that Russia largely ignores the domestic reasons for the violence in Syria and instead considers the conflict mostly from a geopolitical point of view. Official Russian media have consistently accused the Gulf states and the United States of funding the opposition in Syria. This is not entirely false, as documents released by WikiLeaks last spring have shown.

However, the American government’s stance on Syria has been anything but aggressive. After the Iraq withdrawal and the struggling mission in Afghanistan, the U.S. seems rather weary of getting too involved in another country with complicated conflicts and blurred front lines. For Russia, however, support for the opposition from Western nations and the Gulf states seems to be enough to believe official Syrian assertions that the entire opposition is guided from abroad and thus illegitimate. Russia apparently still believes that Assad can maintain stability. The fact, however, that he has not been able to end the conflict in Syria in spite of using ruthless military force against civilians and offering an amnesty makes it doubtful that he will be able to hold on to power for much longer. Russia has shifted its position slightly in recent days and invited the regime and opposition to negotiations in Moscow. The opposition rejected the proposal, demanding that Assad step down first.

The Kremlin risks international isolation with its uncompromising stance on Syria. Western and Arab diplomats reacted to Russia and China’s Feb. 4 veto in the Security Council against an already watered down resolution with anger and harsh criticism. At the same time, it is doubtful whether Russia’s support for a Shiite ruler’s suppression of a mostly Sunni rebellion will contribute to weakening separatist forces in Russia’s own backyard (Russia’s Muslim population in the Caucasus is mostly Sunni).

The proponents of harsher actions against Syria in the Gulf states and the West, however, appear equally confused about how to deal with the Syrian unrest. Belaeff thus believes that Russia might actually play an oddly useful role for its international opponents: “In a perverse way, Russia may be doing the West a favor by its efforts to prevent a Western intervention, which would be prohibitively costly and Pyrrhic for the West.” In the meantime, Syrians are dying.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.