Their ‘Perestroika’

Democracy is ever a fragile thing, especially in states that have no tradition of democratic rule and have, instead, a tradition of self-serving rule by self-appointed and often brutal elites.In “My Perestroika,” Russians reflect on the changes they have witnessed since the early 1980s, when "restructuring" began to reshape their lives.

They are representative of the last generation of students to pass through the old, rigid, heavily politicized Stalinoid school system in Russia—a married couple who now teach in the same school from which they long ago graduated, a street musician who once played in a hot punk band, a single mom with a dead-end job servicing pool tables scattered all over Moscow, and an entrepreneur who has, in a few years, built up a prospering chain of haberdashery stores. In Robin Hessman’s fascinating documentary “My Perestroika,” they reflect—ultimately rather glumly—on the changes they have witnessed since the early 1980s, when perestroika (literally: “restructuring”) began to reshape their lives.

The film is full of surprises, beginning with the fact that their schooling appears not to have been as restrictive as we might imagine. Sure, they were always obliged to sing songs hymning the glories of the Soviet state and to deplore the “evil empire”—that is to say, the United States—to join youth organizations like the Komsomol, a good record in which was essential to obtaining higher education and good jobs later in life. But they were, after all, just kids, full of mischief and minor rebelliousness, and Hessman has uncovered a rich trove of home movies that make their young lives seem not appreciably more repressive than they might have been elsewhere in the world. They seem to look back on those years with a sort of shrugging nostalgia.

Which is nothing compared to their feelings when, in 1991, citizens loyal to the reformist premier Mikhail Gorbachev beat back an attempted coup by hard-line communists intent on restoring the old Stalinist style of governance. Some of Hessman’s witnesses were in the streets, confronting elements of an army that, in the end, refused to support the hard-liners. Some of them were not. But that’s not the point. It was the spirit of those heady days that still moves these witnesses. It was a time when, briefly, everything seemed possible to them—freedom of speech and opinion, freedom to embrace some form of capitalist enterprise, freedom to enjoy the slighty wacky carryings-on of Boris Yeltsin (“eternally young and eternally drunk”).

That spirit could not long continue. There was a power vacuum, into which hard-edged, hard-eyed men like Vladimir Putin flowed. There was also the fact that ordinary citizens could not long live in a state of high political excitement. This is not a point that Hessman overtly stresses, but it is implicit everywhere in her film. There are careers to be made (or, in the case of the street musician, unmade), tragedies to be overcome—the loss of her lover, the father of her child, in the case of the pool table functionary—dachas to be acquired–all the quotidian distractions that ordinary life imposes on us, in Russia no less than everywhere else in the world.

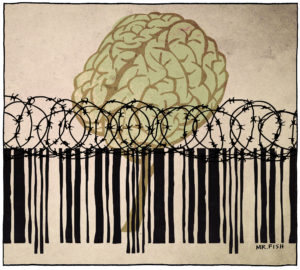

But here’s what’s most interesting about the film: Hessman collected these recollections in Putin’s Russia, and their dominant tone is one of profound cynicism. There is nothing comparable to that spirit elsewhere in the film—even when, as kids, these people are more or less cheerfully faking their enthusiasm for militant communism, certainly not when perestroika makes something like authentic freedom seem possible. Now, however, most of them do not even bother to vote in the election that places at least nominal power in the hands of Putin’s creature, Dimitry Medvedev. Most of them, indeed, are convinced that the election was rigged from the outset, which it may well have been.

Democracy is ever a fragile thing, especially in states that have no tradition of democratic rule and have, instead, a tradition of self-serving rule by self-appointed and often brutal elites. Even idealists, like Hessman’s schoolteachers, are reduced to mild complaints as, basically, they tend to their own gardens. You can see little flickers of hope spring up in them as a new term begins and the shiny-faced kids gather enthusiastically in the yard of a school that has been graduating classes for 131 years, very few of which have produced classes vibrant with idealism. Now, it seems, they will eventually produce one or two millionaires and huge numbers of decent, passive people getting along by going along. I don’t think we should feel too smug about that. Isn’t that pretty much what schools turn out everywhere in economically advanced—or advancing—societies? As Pogo might once have put it, “We have met the [former] enemy and he is us.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.