|

To see long excerpts from “The Sixth Extinction” at Google Books, click here.

|

“The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History”

A book by Elizabeth Kolbert

If best-seller lists and box-office tallies are to be believed, people love survival stories that pulse with human ingenuity, grit and spirit. Yet the demise of creatures other than Homo sapiens — perhaps with the exception of tales featuring precocious children and anthropomorphized mammals — rarely gets human hearts racing or hands sweating, though every living thing is wired to continue its lineage and fight for life to the finish.

Of course, evading extinction is a survival story on a mega-epic scale. Yet most extinctions are very slowly paced, not to mention lacking in dramatic structure. The process of extinction becomes perceptible so incrementally that there’s no drama to structure. Nor is there action to bite one’s nails over: no rolling boulders, dashing heroes or cliffhanging. And although mass extinctions have caused quick crashes — like the asteroid event some 66 million years ago that probably took out three-quarters of Earth’s species, including dinosaurs — fast, in geological time, is thought to be hundreds of thousands of years.

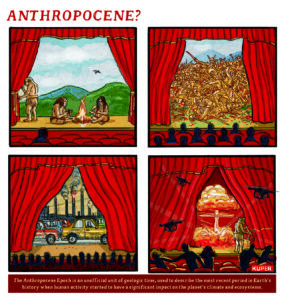

So, much like the efforts to convince oxymoronically named conservatives that Earth in all its facets must be conserved, the packaging of the currently-in-progress sixth mass extinction as a dire drama is a tough sell. And not only that it’s real and dangerous, but also that our own “weedy species” is both collective antagonist and prime target of this unfolding tragedy.

Elizabeth Kolbert proves she is able to frame such realities for maximum impact in her extraordinary book, “The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History.” In both ominous and amusing tones, she weaves together stories of mass and single species extinctions, competing scientific theories through history, and personal observation of current research on waning species to transform this saga of worldwide loss into a riveting read. A Jorge Luis Borges quote, after the title page, foreshadows the ironies within: “Centuries of centuries and only in the present do things happen.”

From the under-appreciated Georges Cuvier, the 18th century naturalist who, after studying mastodon, mammoth and elephant fossils, first realized that species actually go extinct, to Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, and on through lesser known scientific sleuths such as Ken Caldeira, Richard Fortey, Svante Pääbo, and Walter and Luis Alvarez, whose years of international investigation led to acceptance of the K-T asteroid dust theory, the accounts of persistent puzzle solving and knowledge building are wonderfully absorbing. Also striking are the many instances of arrogance, ignorance and misinterpretation that recur throughout these annals of inquiry. Smart deductions often led nowhere; wild speculations sometimes proved to be dead-on. And still there is no widely accepted theory of mass extinction, despite the mounting evidence that humans are involved in, if not actively driving, the sixth one.

Chapter by chapter, Kolbert shows us how scientific history is strewn with unavoidable missteps, myopia and misunderstandings. A discovery might unveil a mystery or deepen it; only gradually can hypotheses be developed, supported, and proved or disproved. And proof is often elusive or dependent on advancements in technology and related fields. Kolbert draws us into winding mysteries, past and present, illustrating the evolutionary nature of both biological life and knowledge. “Even,” she writes, “the idea that the history of life had a direction to it — first reptiles, then mammals — was mistaken, another faulty inference drawn from inadequate data.”

For years, in essays, articles and earlier books, Kolbert has delivered timely, evenhanded reporting, often using the natural world and its foils as her material. She builds stories with vivid imagery, integrating eye-widening details with relatable analogies that make reading “The Sixth Extinction” a pleasure, despite its convincing evidence of impending, and possibly final, human peril. In the section on long-extinct ammonites — nautilus-like marine creatures — she cleverly and memorably compares their chamber usage to an apartment building where only the penthouse is rented. Equally effective are the images she conjures when describing paleogeneticist Pääbo’s work reconstructing broken-down DNA: “Trying to figure out how all the fragments fit together might be compared to trying to reassemble a Manhattan telephone book from pages that have been put through a shredder, mixed with yesterday’s trash, and left to rot in a landfill.”Numerous researchers with wild ideas and the determination to match pop distinctly off the page. Keeping track of the work of each scientist is a challenge because of the range covered, but it’s a stunning volume of seemingly impossible synthesis.

Kolbert provides necessary geological, biological and paleontological background so that lay readers can fully appreciate the alarming number of disappearances. She also has a flair for casually dramatic descriptions of unnatural debacles, and the tracks she lays between observations and understanding are entertaining, sobering and informative. In the chapter on the complex tipping point disaster known as ocean acidification, she sets her stage, following marine biologists gathering samples of victims such as mussels and corals near a tiny island off the coast of Naples, where the surrounding waters are highly acidified. She braids statistics on fossil fuels burned since the beginning of the industrial revolution and the many sorry effects on the air and oceans, with details of the study that include the fun of swimming in water so bubbly from carbon dioxide that it’s “a bit like bathing in champagne.” And did you know that volcanic eruptions are a result of continental Africa drifting northward? That’s also tucked into this absorbing chapter. Elsewhere she corrects a common misconception of how Easter Island was deforested: The culprits were rats, not people. There are myriad fascinating facts and insights, and the deft weave is a key to their accessibility.

In the chapter “Welcome to the Anthropocene,” she opens with a 1949 Harvard experiment on perception that Kolbert notes intrigued the well-known historian of science Thomas Kuhn. It’s also a useful illustration of human resistance to new information and the evolution of understanding: “Data that did not fit the commonly accepted assumptions of a discipline would either be discounted or explained away for as long as possible. The more contradictions accumulated, the more convoluted the rationalizations became.” (Knock-knock, global-warming deniers.) And her writing in the chapter “The Forest and the Trees” on the diversity, utility and vulnerability of our forests is a thing of beauty and sorrow. Like a scientific Hansel & Gretel, Kolbert paves the reader’s path with critical factual morsels, but time and intransigence may prevent us from finding our way back to safety.

Beyond the prodigious scope of knowledge and connecting concepts presented, an intrepid portrait of the author emerges from her descriptions of distances traveled, discomforts endured and awe experienced while gathering data for her readers. She sleeps hoisted in trees, hunts rare toads at night by headlamp, slogs through mud, and wriggles into gooey bat-caves-turned-charnel-houses. There’s no bragging about these exploits, but it’s clear she’s got game. And the less intense or daunting moments in labs, zoos and museums are full of weird science and head-shaking history: a rhino sonogram to help plan in-vitro fertilization, cells of endangered species iced in tanks of liquid nitrogen and sequencing the Neanderthal genome, to name just a few. There is defeat-laced hope in every chapter.

In one that was partly featured in The New Yorker before the book’s publication, Kolbert focuses on a theory that packs a great punch: a prediction by scientist Jan Zalasiewicz that the world will be overtaken eventually by enormous rats, because rats are among the few creatures adaptable enough to make it through the extreme temperatures and other future fallout of global warming. Giant rats — now there’s an image that activists struggling to motivate the public could put to good use. It’s got the visual heft and gross-out power of horror movies, and many people have had run-ins with rodents, so it’s imaginable. Monstrous rats may not be marching down your street soon, but they might be invading your dreams once you see what Zalasiewicz has to say.

Then there are the bats — dead ones, and lots of them. Kolbert’s chronicle of how these puzzling creatures, key to all of our survival as food pollinators, are being felled by fungus is nauseating and unnerving. Much of this story, which has become more desperate with time, ran in The New Yorker almost four years ago, and it’s just as freaky the second go-round. (There’s possibly enough ick factor in the book to appeal to 12-year-old kids, on whom it seems imperative to make a strong impression, since generations of grown-up leaders have responded so inadequately to information about planetary distress. If only we had the time until preteens mature. Or, a real Batman to save the day.)To have shaped this distressing, wide-ranging material into so approachable, engaging and sometimes funny a form is quite an achievement. The author’s sly and smooth maneuvers with prose are especially valuable in a volume with such important bad news. My sole quibble is that the black and white photos underwhelm and add little. But there’s genius synthesis of staggering information here. And yes, “The Sixth Extinction” is heartbreaking. Because despite the many smart, sincere and dedicated people who fill its pages, more often than not, their efforts to understand and stop the devastation of species after species are failing, or worse, too late. As with the ammonites, Kolbert reminds us, there are traits that were advantageous to species for millions of years, until some change made them lethal. Mostly, we are that change.

Still, for the most part, Kolbert writes kindly of our kind, noting that what humans have done to irrevocably alter Earth and “break evolutionary chains” has been largely unintentional, possibly based on something as mundane as restlessness. But despite a growing understanding of our Godzilla-like footprint everywhere we go, our conglomerate behavior continues in the direction of disaster, not preservation. Perhaps that is partly because humans believe we are Earth’s big brains — entitled to dominate and destined to prevail. Interestingly, there are many “lower” species that, although not endowed with free will or Einsteinian IQs, are wired with networking and cooperative abilities that guide them to do far less damage to the commons — and one another — than humans.

We are the one species that seems trapped in a vortex of global destruction, and we can’t find an exit strategy. How much time we have left to react to reality, and accept the connection between us and them-with-the-smaller-brains, is unclear. But the story is pointing toward an unhappy ending. And it will be dramatic.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.