The Normal Heart and Nijinsky’s Faun

We just lived through a year of uprisings round the world, including the Occupy Wall Street movement. In culture, in science and in politics we have every reason to expect that the opening years of this century will be as dangerous and as transformative as the first decade of the 20th.In culture, in science and in politics we have every reason to expect that the opening years of this century will be as dangerous and as transformative as the first decade of the 20th.

Introduction: Fooled by “Fool’s Gold”

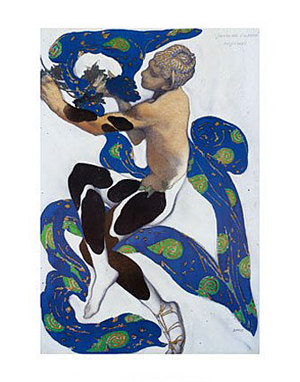

No sooner was My New Year’s Open Letter posted in Truthdig, than I found an article by Joan Acocella (excerpt and weblink below) from the June 29, 2009 issue of The New Yorker posted online. Imagine my surprise. The three video clips of Nijinsky “dancing” on the Ballets Russes site are in fact “computer generated artifacts, made by Christian Comte, a French artist who has a studio in Cannes,” as Acocella reported. And beautiful they are, too, especially the flickering hallucinatory animation of Nijinsky’s Faun. Comte did work from many still photos made by de Meyer, and we do know a great deal about the style and look of the original performance. So this may be as near as we ever get to the 1912 ballet that caused such a storm. Enjoy these artifacts on their own terms, and best wishes in a new year still fresh if no longer new.

Scott Tucker

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker:

“Because, it turns out, these aren’t films. They are computer-generated artifacts, made by Christian Comte, a French artist who has a studio in Cannes. Reached the other day, Comte acknowledged his authorship. ‘These films are animations of photographs, achieved thanks to a process that I invented,’ he said. ‘I work as an alchemist in animated cinema.’ He uses still photographs and, by employing a computer to alter them—tilt a head, move an arm—fills in the gaps between successive shots. That’s why his ‘Faun’ footage is so much longer than his other footage. He had all those de Meyer stills. This is basically no different from the way Steven Spielberg got the dinosaurs to run around the jungle in ‘Jurassic Park.’

For full text of Joan Acocella’s article in The New Yorker, use this link:

http://www.newyorker.com/talk/2009/06/29/090629ta_talk_acocella

Editor’s note: This piece was originally sent out by the author as “An Open Letter for This New Year.”

The Normal Heart and Nijinsky’s Faun

Nijinsky Dancing 100 Years Ago: 1912 film clip of “The Afternoon of a Faun” and a poem by W. H. Auden: “September 1, 1939”

Readers of Open Letter,

Extraordinary! I had thought no film clips existed of Vaslav Nijinsky dancing, since Sergei Diaghilev’s general rule was not to allow filming of his dance troupe, the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev thought that the filmmaking of his day was too abrupt in motion to capture the real nature of dance. Yet it turns out brief film clips of Nijinsky dancing do exist, including a clip from 1912 of him dancing in “L’apres midi d’un faune/The Afternoon of a Faun.” That was also the year of the ballet’s first performance.

That’s the best clip we now have of Nijinsky dancing — so brief it might be remembered dimly from a dream, and yet just long enough to summon his form and movements from light and shadow. Those moments and those movements give some sense of why he is still regarded not only as a great dancer but also as a pioneering choreographer. (Nijinsky’s own notebook of dance notation for that ballet does exist, and has been used by modern choreographers trying to recapture the Grecian vase flattened frieze style of the movements.) Read the introductory text but the three gems here are three very brief clips from early in the previous century, including one going back to 1909. (And once I looked around I found a few more Nijinsky clips on YouTube, easy to find for those interested.) A poem by Stéphane Mallarmé was the inspiration for Claude Debussy’s music, which in turn became the basis for Nijinsky’s dance. The poem, the music, the dance all became signal moments of mutation that changed the evolution of these respective arts.

Here is a good Wikipedia entry on Nijinsky as choreographer, with special focus on “L’apres midi d’un faune.”

Here is a YouTube clip with the first 10 minutes of the Kirov Ballet’s re-creation of Nijinsky’s choreography for “The Rite of Spring,” a ballet that prompted a riot at the first performance in 1913:

Readers will find W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” below. Note especially the sixth stanza: “What mad Nijinsky wrote / About Diaghilev / Is true of the normal heart. … ” What exactly did Auden mean by “the normal heart”? Oh, that would require reading all of Auden’s work and not just one poem. But I will dare to say Auden did mean human nature, and more particularly (given Auden’s shift from Marxist to Christian views) human nature in a fallen form. But anyone who had read Nijinsky’s diary (written during a breakdown, after which he never fully regained sanity) would have understood even in 1939 that Auden was writing in the classic form of an open secret. When an English (and considerably expurgated) edition of Nijinsky’s diary was first published in 1936, it was indeed already an open secret among many people in the arts that Nijinsky had been in a troubled affair with Diaghilev. Nijinsky’s vegetarian diet, his aversion to bankers and business, his simple faith in God all led to certain social misunderstandings that caused him pain even before his psychic breakdown. In his diary, Nijinsky recounts a fellow traveler on a boat who suspected him of holding the political views of the Russian Nihilists, but Nijinsky always placed God first, art second and politics far off-stage. The Diary Review includes a few excerpts from Nijinsky’s diary.

The reference to Nijinsky and Diaghilev was one way Auden could refer to the erotic “other” and still get away with it, still under the heavy influence of Freud, of his own chilly British upbringing and of “normal” prejudice against queers. (Yes, the title of Larry Kramer’s play “The Normal Heart” is drawn from Auden’s poem. I can’t recommend Kramer’s play, except as a piece of forensic evidence. It’s like revisiting the scene of a crime, in this case a melodrama in which even the characters calling for enlightenment bear the heavy shadows of the old regime. I wish I could say that this was the Brechtian and “dialectical” message of Kramer’s play, but Kramer is one of the least Brechtian dramatists and political writers to be found, dead or alive. On several issues of critical importance during the AIDS epidemic, Kramer was of course correct. His timing and courage counted. But his worldview also counted against him, since he takes the official culture of the Ivy League and Wall Street all too much to heart in his distinctly brokenhearted way. Others in the AIDS activist and health care movements had much wider political horizons, less moralism, and no attachment to being chief executive officers of any wing of any movement. As for Kramer’s influence upon the politics of ACT UP, that is a complex subject. I say that as a former activist in ACT UP, and as a democratic socialist — but that subject can be only noted here, not pursued.)

In later life, Auden claimed he was “ashamed” to have written this poem (and certain others from his early manhood). Auden was emphatically a philosophical poet, and he was drawing different philosophical boundaries by the time he claimed to see through the illusions of youth. When he gave permission for “September 1, 1939” to be republished in an anthology of poetry in 1955, he altered the single most famous line in the poem (and perhaps the single most famous line Auden ever wrote in poetry or in prose) by changing one word. Auden changed the line “We must love one another or die” to read “We must love one another and die.”

How to choose between those two lines? Both are true, but each belongs to a different season of life. The first line is not simply optimistic, for Auden’s poem was written against “the romantic lie” during a time of war. Nor is the second revised line simply pessimistic, for Auden’s prevailing view in later life was more nearly stoic, more nearly a statement of fact: If we are lucky, we find love (not just personal love, but “universal love” in some form), and then, yes, we die. The first line is more conventionally lyrical, whereas the revised line is more linear in the sense that all our stories and timelines end in death. Precisely because the revised line is more linear and disenchanted, it more nearly reflected Auden’s later life and ideas.

Auden’s anti-romantic views were by no means anti-sexual as such, neither in his early or later life. Even in the scope of one poem such as “September 1, 1939,” Auden the anti-romantic could speak of “The romantic lie in the brain / Of the sensual man-in-the-street,” and then in the last stanza (and in his own strain of stoic romance) assure the readers that he, too, is “composed like them / Of Eros and of dust. … ” In poetic terms, that kind of tension within a single sensibility really is dialectical; and although Auden had never read Marx with great understanding, he had learned real lessons in form and style from Bertolt Brecht.

For more background on the writing and publication of this poem, this Wikipedia entry is good.

Do I agree with every line and idea to be found in this one poem by Auden? No, I do not. For example, Auden proclaiming, “There is no such thing as the State” is just too close to Margaret Thatcher proclaiming, “There is no such thing as society.” Auden took care to put a capital S on state (which actually emphasizes precisely the thing-like alienation we may associate with the state, and makes Auden’s poem belong in the anti-authoritarian tradition). One of Thatcher’s defenders (in the U.K. Telegraph) claimed that she was using the word society with polemical quotation marks, namely, with irony directed at left-wingers who demanded rights for all and responsibilities for none. (That is one construction of her words in context.) Readers can decide for themselves what Auden and Thatcher each intended to say on the subject of public life and personal responsibility.

Auden gave direct aid to Dorothy Day (a social gospel Catholic who was living and working among the poor), but not any direct help (as far as I know) to the secular social revolutionaries of the second half of the 20th century. In most respects, he accommodated himself to his milieu in later life, rather than breaking from it — even before his heavy smoking and drinking had ruled out front-line resistance. Auden was contemptuous of “The windiest militant trash / Important Persons shout”– note once again the capital P, for capital letters are never accidental with Auden — and yet he lived long enough to live under a regime of militarists in the United States shouting windy trash about democracy while firebombing vast tracts of Vietnam. Auden did not show the civic courage of other poets and writers in defending civil rights and opposing the Vietnam War (which the Vietnamese more truly call the American war). Solidarity with feminists and gay activists played no part in Auden’s public persona. Yet if we read him, personally and politically, only as a reactionary “in the last analysis,” then we miss the motions of a mind trying to respond with sanity to a culture gone crazy.

Those interested in a conservative defense of Thatcher’s most infamous words should read The Telegraph article.

We just lived through a year of uprisings round the world, including the Occupy Wall Street movement. In culture, in science and in politics we have every reason to expect that the opening years of this century will be as dangerous and as transformative as the first decade of the 20th. We must work to make sure the next century is not also an era of wars and hunger and reckless plundering of nature. Some of you believe such political work is compatible with the ordinary functioning of “our two party system,” and I most surely do not share such a belief. But for once that is not my main message in Open Letter.

Following a good general rule for open letters, the personal dimension is properly subsumed in the political. Let politics unite or divide us as necessary, but in common humanity the bloody basement of the Lubyanka and the militarists in our own government must both be ruled out of order. The impersonal, and indeed lethal, machinery of the state is all too real. That was one lesson of the last century we are still learning in 2012. Obama, for example, may be commander in chief, but he can hardly be said to be in full command of the busy drones, which have a momentum of their own backed up by the whole power of capital and of military industries. He chose his current job, but he truly serves at the discretion of the ruling class.

Each in our own sphere of influence, each in our own job or calling, we at least may choose to live with fewer illusions. Only certain adolescents and lifelong romantics believe art has all the answers. No, art is one human activity among others, and no more innocent of class culture than science and politics. But this much we can say soberly: In this global movement toward democracy and human rights, artists and writers also take our place.

“Show an affirming flame,”

Scott Tucker

================

By W. H. Auden

I sit in one of the dives On Fifty-second Street Uncertain and afraid As the clever hopes expire Of a low dishonest decade: Waves of anger and fear Circulate over the bright And darkened lands of the earth, Obsessing our private lives; The unmentionable odour of death Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can Unearth the whole offence From Luther until now That has driven a culture mad, Find what occurred at Linz, What huge imago made A psychopathic god: I and the public know What all schoolchildren learn, Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew All that a speech can say About Democracy, And what dictators do, The elderly rubbish they talk To an apathetic grave; Analysed all in his book, The enlightenment driven away, The habit-forming pain, Mismanagement and grief: We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air Where blind skyscrapers use Their full height to proclaim The strength of Collective Man, Each language pours its vain Competitive excuse: But who can live for long In an euphoric dream; Out of the mirror they stare, Imperialism’s face And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar Cling to their average day: The lights must never go out, The music must always play, All the conventions conspire To make this fort assume The furniture of home; Lest we should see where we are, Lost in a haunted wood, Children afraid of the night Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash Important Persons shout Is not so crude as our wish: What mad Nijinsky wrote About Diaghilev Is true of the normal heart; For the error bred in the bone Of each woman and each man Craves what it cannot have, Not universal love But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark Into the ethical life The dense commuters come, Repeating their morning vow; “I will be true to the wife, I’ll concentrate more on my work,” And helpless governors wake To resume their compulsory game: Who can release them now, Who can reach the deaf, Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice To undo the folded lie, The romantic lie in the brain Of the sensual man-in-the-street And the lie of Authority Whose buildings grope the sky: There is no such thing as the State And no one exists alone; Hunger allows no choice To the citizen or the police; We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night Our world in stupor lies; Yet, dotted everywhere, Ironic points of light Flash out wherever the Just Exchange their messages: May I, composed like them Of Eros and of dust, Beleaguered by the same Negation and despair, Show an affirming flame.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.