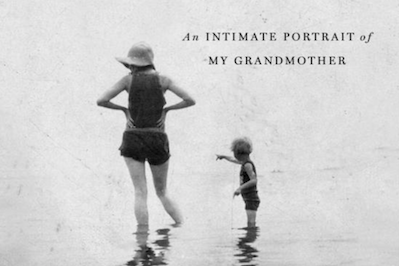

Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty

A granddaughter of the journalist and founder of the Catholic Worker Movement explores the relationship between Day and her only child.

Scribner

“Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved By Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother”

A book by Kate Hennessy

Kate Hennessy, now middle-aged, is the ninth and final grandchild of Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement. Hennessy was born into a family suffused with chaos, regret and deeply buried resentments. Determined to piece together the genuine story of her family and her famous grandmother, which contrasts greatly with the sanctified image of Dorothy Day, who has been nominated for canonization by the Catholic Church, Hennessy has written a mesmerizing memoir filled with compassion and acute perceptions, as well as uncomfortable truths.

Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother

Purchase in the Truthdig BazaarDorothy Day’s conversion to an unwavering Catholicism came after spending her young life intoxicated with and wholeheartedly participating in a radical, free-spirited bohemian lifestyle. She embraced many radical ideologies: anarchism, socialism, vegetarianism and communism. She wanted to change the world. She had many lovers, and was a close friend of Eugene O’Neill, with whom she spent nights walking through Manhattan. He gave her his plays to read and cherished her feedback, while encouraging her to write as well.

Dorothy Day was born an Episcopalian in 1897, the daughter of a journalist who was a hard drinker and a womanizer. She became pregnant by one of her lovers and aborted the child, a decision she immediately regretted. When she got pregnant again with her daughter Tamar, she converted to Catholicism. The child’s father, Forster Batterham, to whom she was not married, quickly retreated from the responsibilities of fatherhood and detested her growing religiosity. Their relationship ended. After this love affair and her conversion and baptism, she chose to remain celibate for the rest of her life, even though she was still a very young woman.

Tamar Hennessey, Day’s only child, spent her young life being shipped off to boarding schools or left with relatives and neighbors as her mother built the Catholic Worker enterprise. This movement included a newspaper that once peaked at over 100,000 subscriptions, and establishing houses of hospitality to feed the poor, as well as developing communal farms for the homeless and destitute. Dorothy Day wrote endless columns for the Catholic Worker newspaper about the causes that moved her: the plight of the sharecroppers in the South, Hitler’s persecution of the Jews, the workers’ strikes and the refusal of the church hierarchy to do more for the poor. She supported Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers, and the Cuban revolution that she believed would help the poor. She spoke out against atheism, and was a staunch pacifist, even speaking out against the United States’ decision to enter World War II — a decision that was widely panned by her readers. She never embraced feminism because of its stand on birth control and abortion.

Tamar was a shy and inarticulate young child, further traumatized by her mother’s frequent absences. Tamar married very young — her husband was an abusive alcoholic — and began having one child after another. The author’s father left the family shortly after her birth. She remembers her mother constantly working to keep up with the demands of her nine children. She was forever weaving, spinning, planting, cooking and tending the animals on the farm where they lived in dire conditions. Dorothy Day occasionally sent money or dropped in to lend a helping hand when it suited her, but Tamar was on her own.

Kate Hennessy read her grandmother’s diaries two weeks after her mother’s death. She was moved by her grandmother’s frequently repeated exhortation, inspired by Dostoyevsky, “The world will be saved by beauty.” But she had difficulty squaring this lofty rhetoric with the reality of her mother’s life. She reveals to us how her project began:

“On the morning after I finished reading I lingered in that half-sleep state where both dreams and reality take on a different quality altogether. … And in that moment I felt, sure and true, the knowledge of both Tamar and Dorothy’s lives with all their memories and I was overcome by this knowing. I felt the weight and miracle of their lives, and I wondered if I were strong enough — wise enough — to tell this story. But haven’t I been working on it all my life, living in their wake and stumbling along, trying to make my own way?”

Tamar confessed that she often felt terribly distraught as a child and came to dislike the church’s teachings on birth control and sex. She was put off by the controlling and paternalistic church hierarchy, and stung deeply by her mother’s refusal to recognize her frequent distress, which was often ignored or scolded. Tamar also found her mother’s growing piousness off-putting; it made her more distant and intolerant of anyone who did not follow her stringent rules. None of Tamar’s children became practicing Catholics except for one daughter, Martha. Hennessy was deeply disturbed by her mother’s revelations about Dorothy Day, but remained impressed by the scope of her grandmother’s accomplishments. She writes at great length about Catholic Worker co-founder Peter Maurin, who could “provoke people into thinking.” He introduced Day to the work of great intellectuals like Romano Guardini, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc and Emmanuel Mounier. He would talk to Day for hours, leaving her head reeling. Hennessy tries to comprehend how her grandmother transitioned into a life of pious faith after her wild beginnings, but has trouble understanding what pulled her in and never let go. She describes her grandmother as a restless woman, prone to migraines and bouts of melancholy, which did not disappear when she became a Catholic. It seemed Catholicism provided her a structure and umbrella for her torment and allowed her a modicum of peace.

But Hennessy is more concerned with the concrete reality of her mother’s life. She recalls tenderly how often her mother used to say softly, “All we need is lovingkindness.” We can feel the author’s anger is at how little lovingkindness her mother received. Dorothy Day’s own voluminous writings include essays about the loneliness and difficulty of childrearing. Day conceded the frustration she herself felt when she was left alone with a young Tamar who kept her from pursuing her dreams. Day knew that women needed more than the love of their families and that they could wither from the lack of an interior life. Day also understood that her daughter’s life did not permit her any of the freedoms Day herself had. Day spent much of her life pursuing the common good and performing countless selfless acts, but she was a free woman. She read, wrote, traveled, lectured and spoke her mind without fear of condemnation. When overwhelmed, as she often was, she loved to take to the road. She may have publicly scorned feminism, but she lived the life of a full-blown feminist. It reminds me of another woman, the late Phyllis Schlafly, who toured the country touting the cherished sphere of motherhood and domesticity, but never seemed to be at home to enjoy it.

Kate Hennessy forces us to reckon with the disparity between a person’s public acts and proclamations, and their private behavior. Dorothy Day did try to do much good for the world and those who had nothing, but failed in key ways to nourish her only daughter. How do we square that? Hennessy seems to be showing us the quiet heroism of her mother’s ongoing love as more significant and selfless than anything her grandmother did, and it is hard to disagree with her hard-wrought assessment. This moving and fiercely intelligent memoir has allowed Hennessy to finally find her place in her own family’s complicated legacy. She is nothing less than their fearless truth teller, and she bears the scars of the role she has chosen for herself.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.