Legacy Admissions Challenged Due to Affirmative Action Decision

Diversity advocates are pushing to end legacy admissions while conservatives are taking steps that will make it harder for students of color to go to college. Harvard students Shruthi Kumar, left, and Muskaan Arshad, join a rally with other activists as the Supreme Court hears oral arguments that could decide the future of affirmative action in college admissions, in Washington, Oct. 31, 2022. Photo: J. Scott Applewhite / AP.

Harvard students Shruthi Kumar, left, and Muskaan Arshad, join a rally with other activists as the Supreme Court hears oral arguments that could decide the future of affirmative action in college admissions, in Washington, Oct. 31, 2022. Photo: J. Scott Applewhite / AP.

Originally published by The 19th.

Your trusted source for contextualizing education and politics news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

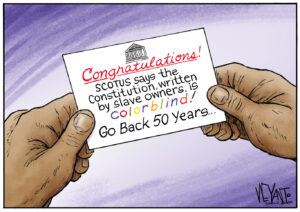

After the Supreme Court’s ruling last month effectively ending affirmative action in higher education, lawmakers and organizations on both sides of the ideological divide strategized next steps ranging from challenging legacy admissions to barring minority scholarships.

In a consolidated decision in two cases—Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. University of North Carolina and Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College—the Supreme Court decided that affirmative action is unconstitutional.

Harvard is now under fire for admissions policies that activist groups say disadvantage students of color, while Republican officials in Texas, Missouri and Wisconsin are taking aim at diversity efforts at the states’ colleges and universities.

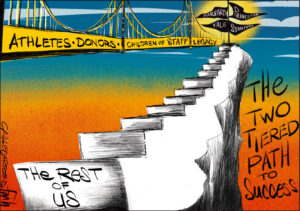

The Boston nonprofit Lawyers for Civil Rights (LCR) filed a July 3 complaint against Harvard with the Department of Education “to challenge the discriminatory policy of offering preferential treatment to overwhelmingly White applicants with family ties to Harvard donors and to Harvard alumni,” Michael A. Kippins, an LCR litigation fellow, told The 19th. “Applicants with these ties are six to seven times more likely to be admitted.”

Nearly 70 percent of students admitted to Harvard through these preferences are White, Kippins said. He added that these admissions practices have “nothing to do with individual merit” and called them “unfair and an unearned preferential treatment.”

The Ivy League school is far from the only higher education institution to use these preferences.

More students of color would be admitted to Harvard if the school eliminated its preferences for the children of alumni and donors, according to the LCR complaint filed on behalf of the Greater Boston Latino Network, the Chica Project and the African Community Economic Development of New England. “A spot given to a legacy or donor-related applicant is a spot that becomes unavailable to an applicant who meets the admissions criteria based purely on his or her own merit,” it states.

Lawyers for Civil Rights wants the Department of Education to prohibit these admissions preferences, leaving Harvard no choice but to end these practices since it receives federal funding. More than 100 colleges have ended legacy admissions since 2015, advocacy group Education Reform Now reported in a 2022 analysis. And a Washington Post poll of 1,238 adults published in October found that three quarters of respondents think legacy admissions are inappropriate.

“We are fully confident that federal authorities will launch an investigation based on our complaint and that they’ll take a closer look at how donor and legacy admissions work in the process,” Kippins said.

Harvard has said that it will not comment on the complaint.

Although Justice Neil Gorsuch was part of the 6-3 Supreme Court majority who voted to end affirmative action, he argued in his concurring opinion that Harvard’s admissions preferences for special status students fuel inequity on college campuses.

“Its preferences for the children of donors, alumni, and faculty are no help to applicants who cannot boast of their parents’ good fortune or trips to the alumni tent all their lives,” Gorsuch wrote. “While race-neutral on their face, too, these preferences undoubtedly benefit white and wealthy applicants the most. Still, Harvard stands by them.”

The Ivy League school is far from the only higher education institution to use these preferences. Legacy students make up nearly a quarter of the student population at some elite universities, even outnumbering the total Black student population on campuses, according to an Associated Press analysis. While the Lawyers for Civil Rights complaint takes aim at Harvard’s admissions process specifically, Kippins said that his group expects it to set a national precedent for enrollment standards.

“We at Lawyers for Civil Rights believe that college admissions should not be a pay-for-play operation,” he said.

The NAACP is also calling on universities to end legacy admissions as well as hire diverse faculty and drop college entrance examinations. When COVID-19 lockdowns began, dozens of colleges and universities temporarily scrapped the SAT and ACT as admissions mandates. Many have since made that decision permanent because they attracted a more diverse applicant pool afterward. Additionally, the NAACP is urging colleges and universities to recruit low-income and first-generation students, echoing President Joe Biden’s June 29 remarks encouraging admissions officials to consider whether students have overcome adversity on their path to higher education.

Since 1998, Texas has guaranteed admission to its public universities to residents who graduate in the top 10 percent of their high school classes, a model viewed as an affirmative action alternative.

Using adversity in admissions has potential risks, said Paige Duggins-Clay, chief legal analyst for the Intercultural Development Research Association, an education nonprofit in San Antonio.

“It’s problematic because students of color do face tremendous amounts of adversity and trauma, and forcing students to lay that out in ways that are connected to an institution’s admission is a really traumatic exercise,” she said. “We’re now putting college admissions officials potentially in the position of having to weigh which adversity is the worst and whose adversity matters. I think that’s really dangerous, and we’re forcing students of color and their families to tell stories that can be dehumanizing and traumatizing and painful in ways that may discourage them from the process altogether.”

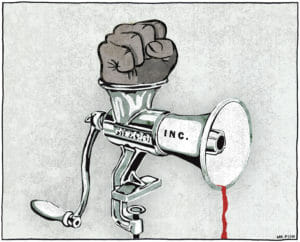

As supporters of affirmative action push for universities to continue their work toward diversity, Republican lawmakers are taking steps that critics say would undo the gains that people of color have made in higher education.

Just hours after the Supreme Court’s ruling on race-conscious admissions last month, Texas Rep. Carl Tepper filed House Bill 54 to codify an affirmative action ban for the state’s public universities and colleges, even though just one school in the state, University of Texas-Austin, employs the policy.

“Make no mistake, the extremist elite who are orchestrating all of these multi-pronged attacks on affirmative action, on DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion], on all of the programs, policies and practices that support students of color accessing higher education — they have no interest in real educational opportunity, and this is really part of a broader agenda to dismantle the civil rights protections that have created opportunity for those who have been systemically pushed out,” Duggins-Clay said.

She pointed out that Texas in June also enacted legislation to dismantle DEI offices in colleges and universities and defund personnel who support students of color and those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“There’s no other explanation for why policymakers would go down this path other than discrimination,” Duggins-Clay said.

Since 1998, Texas has guaranteed admission to its public universities to residents who graduate in the top 10 percent of their high school classes, a model viewed as an affirmative action alternative. Research, though, has shown that the 10 percent plan has done little to increase the representation of Black and Latinx Texans at the state’s most selective universities.

“One of the reasons that it has not been rolled back is because White rural students benefit tremendously from it,” Duggins-Clay said. “Texas is a big state, and so allowing students from all across the state automatic admission really serves those communities well, but race-neutral policies like the top 10 percent plan have never been enough to ensure that every student has a fair shot to go to college. We really need to think even more deeply about how to support students in getting into our nation’s top institutions.”

In Missouri and Wisconsin, conservative lawmakers are making headlines for plans that might make it harder for students of color to access higher education.

Shortly after the Supreme Court decision, Andrew Bailey, Missouri’s Republican attorney general, directed universities to “immediately cease their practice of using race-based standards to make decisions about things like admission, scholarships, programs and employment.”

The University of Missouri had previously factored race or ethnicity into some of their scholarships. “Those practices will be discontinued, and we will abide by the new Supreme Court ruling concerning legal standards that applies to race-based admissions and race-based scholarships,” a university spokesperson announced in a statement.

Preventing these undergraduates from getting the financial help they need would create yet another barrier for them.

In Wisconsin, Robin Vos, the state assembly speaker, said via Twitter that he intends to “introduce legislation to correct the discriminatory laws on the books and pass repeals in the fall” related to grants for undergraduates of color. Vos stated this after an attorney on the networking site suggested the Wisconsin legislature take steps “such as fixing numerous scholarships, grants and programs that exclude millions of Wisconsinites because of their race” following the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ruling.

Vos did not respond to The 19th’s request for comment.

Angelique Albert, CEO of Native Forward Scholars Fund, which has provided financial support for tribal citizens pursuing higher education for more than 50 years, disagrees that grants and scholarships for undergraduates of color constitute anti-White discrimination. Taking action to block such support “is very egregious,” she told The 19th. “It’s a direct effort to ensure that Brown and Black people of this country do not have access to education.”

As it is, Alpert expects the percentage of Native American students at colleges to plummet following the Supreme Court’s decision to end affirmative action. Preventing these undergraduates from getting the financial help they need would create yet another barrier for them. “There’s already a lot of brilliant scholars who can’t go to college because they don’t have the money to do so,” she said. A national study on college affordability for Indigenous students published last year found that financial hardship is a major reason they don’t complete their higher education.

Native Forward, Alpert said, is only able to offer support to 14 percent of the scholars who apply for aid. She added that objecting to scholarships based on race is hypocritical given the role race has played in the nation’s history.

“The campuses that our students are going to—they were built on land that was stolen from our Native people,” Alpert said. “The wealth of the institutions—they were built off of the land that was stolen from my Native ancestors, and, quite frankly, the wealth of this country was as well. So our Native students—they don’t have the generational access to education. They don’t have the generational wealth of my White ancestors, so we don’t have the same opportunities.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.