Asian Americans and Affirmative Action: An Interview with Jeff Chang

What the media obsession with Ivy League lawsuits gets wrong about Asian Americans and higher education. Image: Jeff Chang

Image: Jeff Chang

Janine Jackson interviewed cultural critic Jeff Chang about Asian Americans and affirmative action for the June 2, 2023, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

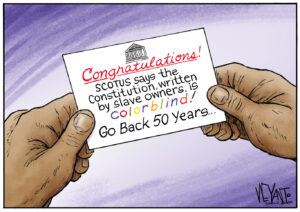

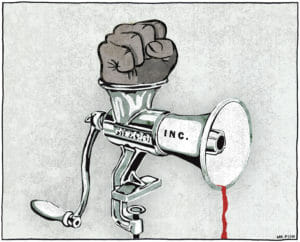

Janine Jackson: After the Supreme Court failed to find that Abigail Fisher had been denied admission to the University of Texas due to racial discrimination against white people, anti-equity activist Ed Blum announced that he “needed Asian plaintiffs” to further the mission of eliminating affirmative action policies from college admissions.

That’s the short version, and the basic context for the cases Blum’s group, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., is bringing against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, cases the Trump-stacked Court will likely rule on in June.

Affirmative action has always been a difficult topic for a press corps more comfortable talking about individual racists than systemic white supremacy, and worlds more happy to gesture towards buying the world a Coke than to unpack the particulars of what actually needs to happen to get to anything like equity or reparation for marginalized people.

So these are things we should look out for in the coverage we may see on the Court’s possible upcoming ruling.

Jeff Chang is a writer and cultural critic, and author of, most recently, We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes on Race and Resegregation, and of course 2005’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. He was a co-founder of the Student Coalition for Fair Admissions, organized at UC Berkeley in 1987, and he joins us now by phone. Welcome to CounterSpin, Jeff Chang.

Jeff Chang: Thank you so much for having me, Janine.

And what we begin to see in the universities is this bearing fruit in the 1970s and the 1980s. What you see, though, is by the 1980s, because of immigration, there’s a much larger population of Asian-American students who are applying for elite universities.

And so at that time, universities begin to quietly, and sometimes loudly, take Asian Americans off of equal opportunity programs, despite the fact that there are a number of Asian-American ethnicities, such as Filipino Americans and Southeast Asian Americans, who were still deeply underrepresented.

And, of course, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders continue to be deeply underrepresented in college admissions and university admissions all across the US.

So at that particular time, what we also see is a surge of applications from this new generation of immigrants, and universities are also experiencing concern from white alumni about the competition that these Asian-American immigrants, this new generation, is providing against their sons and daughters at elite universities, where, in the past, legacy admissions have preserved their entitlement to slots at universities like Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

So in the beginning of the ’80s, what we begin to see is this plateauing of the number of Asian Americans who are actually admitted to these universities, and community advocates in the Asian-American community begin to get really concerned, because the number of applications is still skyrocketing, but the number of admissions is plateaued.

And what we begin to see in the universities is this bearing fruit in the 1970s and the 1980s. What you see, though, is by the 1980s, because of immigration, there’s a much larger population of Asian-American students who are applying for elite universities.

And so at that time, universities begin to quietly, and sometimes loudly, take Asian Americans off of equal opportunity programs, despite the fact that there are a number of Asian-American ethnicities, such as Filipino Americans and Southeast Asian Americans, who were still deeply underrepresented.

And, of course, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders continue to be deeply underrepresented in college admissions and university admissions all across the US.

We’d be going back a century or more in time, to a period in which campuses were less diverse than we could even imagine at this particular point.

So at that particular time, what we also see is a surge of applications from this new generation of immigrants, and universities are also experiencing concern from white alumni about the competition that these Asian-American immigrants, this new generation, is providing against their sons and daughters at elite universities, where, in the past, legacy admissions have preserved their entitlement to slots at universities like Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

So in the beginning of the ’80s, what we begin to see is this plateauing of the number of Asian Americans who are actually admitted to these universities, and community advocates in the Asian-American community begin to get really concerned, because the number of applications is still skyrocketing, but the number of admissions is plateaued.

And so there’s this huge gap that they want to explore. And when they do, especially at UC Berkeley, under the leadership of a group of community leaders there and a professor named Ling-Chi Wang, they find that there have been a number of different types of changes that have been made in the admissions process that have actually discriminated against Asian Americans disproportionately and excluded them from admissions.

And as studies pop up all across the country at Brown University, at UCLA, at a number of other universities around the country, folks begin to find the same kinds of things happening.

JJ: And then the idea that there could be anti–Asian American bias in college admissions, but that that is not due to affirmative action policies, here’s where the conflation occurs, and where the co-optation of the narrative occurs.

JC: That’s exactly right. What Asian Americans are arguing for at this particular point is a sense of fairness in what is supposed to be meritocratic competition between white and Asian students for these slots.

Affirmative action is a completely different track, and students are judged for affirmative action by a different set of standards, because of the importance of increasing diversity in these elite universities. That’s what the Supreme Court has ruled, over and over again.

And really, actually, if we go back, affirmative action was begun as a remedy for historic discrimination. And so that’s the way that I think a lot of communities of color are seeing the need for these affirmative action programs, despite the fact that before the court, the only justification for affirmative action programs now, because of the Bakke case in 1978, is this idea of “diversity.”

Now, getting to a lot of different types of things, but the main point here is to note that the Supreme Court, by getting rid of the historic discrimination standard for affirmative action programs, has moved to this much lighter…

JJ: Mushier.

JC: …much more white-friendly idea of diversity. That is the main justification now before the law for these affirmative action programs to exist.

But what happens with Asian Americans is, you have Asian Americans here aiding diversity, right? And at the same time, you have white admissions officers, in order to please white alumni concerned about their children getting into these universities, tweaking the system, so that Asian Americans are less competitive in comparison to white candidates, in this supposedly pure, meritocratic, color-blind system.

JJ: Absolutely. And when I hear “diversity” as a goal, it sounds to me like a perk for white people, like sprinkles on the sundae. White people deserve to be on top, but to be surrounded by and “learn from” the people they’re on top of.

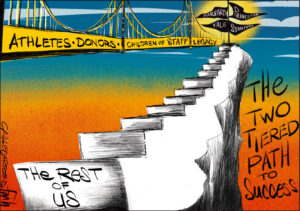

Diversity is something that is a good thing; and this just leads directly to–and listeners may know this, but it doesn’t appear, particularly, in a lot of media conversations–you hear Harvard’s very “competitive,” and Asian people and Black and brown people are fighting for spots at Harvard. And it’s like, those are the spots that are left over after we get through ALDC. And maybe you could explain what that is.

JC: First, to go back, the main question becomes “who is diversity for?” And the diversity standard really was developed by Harvard as an alternative justification for the equal opportunity programs that they were instituting in the 1960s and the 1970s, as an alternative to recognizing that, historically, they’d excluded women, they’d excluded non-Protestant people–Catholics and Jewish people–and that this was really a way for them to preserve a sort of elite student body that they wanted to sculpt in their own image.

And so we have to kind of go back to that. We have to mention that, we have to note that, when we’re talking about the programs that we’re talking about now.

And what they created, at the same time, was this notion of legacy admits, right? The technical term for it are ALDC admits, and this includes athletes, legacy admits, the Dean’s preferred lists, children of faculty and staff.

These are all preferential treatment slots that were given out, even before equal opportunity programs had come into play in the 1960s. This is, again, to preserve privilege and wealth for a certain class of folks.

And even now, when we look at white admissions to Harvard, 43% of them are noncompetitive ALDC admits. And so the idea of preferential programs being just for Black and brown students, for poor students, that’s a recent development.

Even now, right, we’re talking about the large proportion of white students being admitted to Harvard via preferential treatment.

And so now, when we talk about what should these classes look like, and we have a case before the Supreme Court which would basically make it impossible for elite universities to be able to bring in students who are not white, we have a situation in which we’re solving a problem that’s just for elite universities, and, in fact, inflicting that on the rest of society. And the results would be disastrous.

The results would be the resegregation of higher education. We’d be going back a century or more in time, to a period in which campuses were less diverse than we could even imagine at this particular point.

JJ: And not to put too fine a point on it, but I think when people hear about Ed Blum and plaintiff-shopping and knowing that, oh, on the other days of the week, he’s opposing voting rights, he is obviously, and his group, are clearly not really concerned about equity across difference.

But even besides that consider-the-source argument, if this case wins in the Court, it really doesn’t mean anything extra good for Asian Americans. The people who are nominally the plaintiffs here, the cases themselves don’t have anything in particular to do with Asian Americans, in terms of their likely outcome.

JC: We’re talking about a group that calls itself Students for Fair Admissions. And the important thing to note is that they’ve never produced any students in any of the testimony, and they’ve never presented any Asian Americans in their testimony. And so that goes to tell you, at least on the surface….

JJ: It’s not a class action, it’s not a class action.

JC: It’s not a class action suit. And the other thing to note is that, look, there’s more Asian Americans who are enrolled in San Francisco City College than there are in the entirety of the Ivy Leagues.

Asian Americans are standing against Ed Blum and his anti–affirmative action cohort, because they know that what’s best is equal opportunity for all.

And so if the argument here is that this is going to support opportunity for Asian Americans in the main, that’s not the case. We’re talking about a small number of Asian Americans who are applying to this elite university, in numbers below a thousand, probably, every year, or in the low thousands, probably, across the Ivy Leagues every year. So, very much not the majority of Asian Americans.

JJ: And that leads me to media coverage, because, media are certainly tossing around, and we can expect more of it, just “Asian American” as a term, as though they’re a monolith, and that there was nothing of particular value in exploring different communities.

And I just wonder, what would you ask for from media in terms of addressing this? I mean, maybe hope for, maybe dream of, but what would good coverage look like?

JC: Yeah, I think good coverage would include this long, long history that Asian Americans have had of participating in arguing for equal opportunity programs, for affirmative action programs, for civil rights programs.

It would be much more, I think, realistic about the way that Asian Americans actually feel about affirmative action in this particular moment in history, which is that they support it. And I think it would be much fairer about looking at what the real needs are of Asian Americans across the board.

Asian Americans are standing against Ed Blum and his anti–affirmative action cohort, because they know that what’s best is equal opportunity for all, right?

And I think that that’s something that is really downplayed in the media, where there’s a focus instead on the minority of Asian Americans who have been advocating against affirmative action, and against desegregation in public schools and public high schools in a select number of cities on the coast.

And so that, I think, would be a much more realistic view of where Asian Americans stand in relationship to this issue.

JJ: So it has to do with who they talk to, really.

JC: Yeah. And I think it also has to do with the lack of understanding of what Asian Americans have been through historically in the US, and how our communities have been shaped. And so it’s really part of a larger thing about representation of Asian Americans in our true light, in our full humanity.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Jeff Chang. You can find his piece, headed “Asian Americans Spent Decades Seeking Fair Education. Then the Right Stole the Narrative,” online at TheGuardian.com. Jeff Chang, thank you very much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

JC: Thank you so much.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.