The Existential Dilemma of Offshore Riches

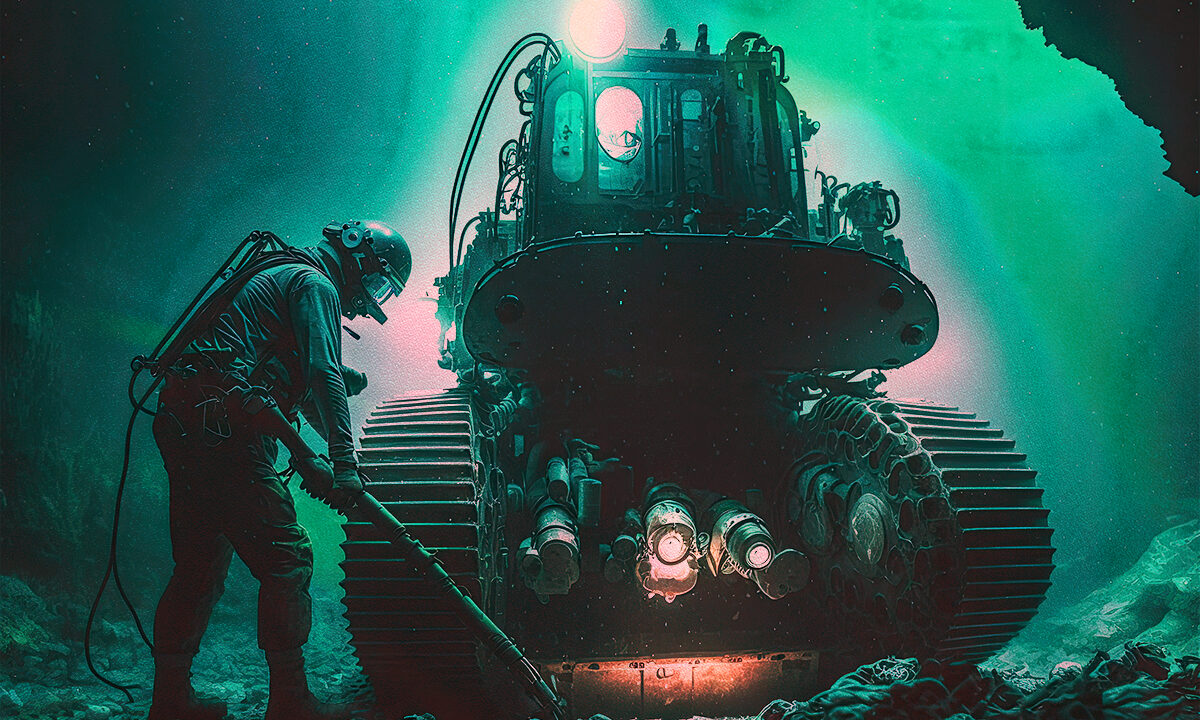

The Cook Islands and other Pacific island nations are considering opening their oceans to mining. Is it worth the risk to their way of life? While the government has access to some historical data collected during surges of interest in seabed minerals between the 1970s and 1990s, little is known about the deep sea in the Cook Islands. (Image: Adobe)

This is Part II of the "The Scramble for Deep-Sea Minerals" Dig series

While the government has access to some historical data collected during surges of interest in seabed minerals between the 1970s and 1990s, little is known about the deep sea in the Cook Islands. (Image: Adobe)

This is Part II of the "The Scramble for Deep-Sea Minerals" Dig series

On an overcast morning in March, a few dozen residents of the Cook Islands gathered to welcome visitors to the Port of Avatiu on the northern coast of Rarotonga, the country’s most developed island, with a traditional Māori ceremony. Beside a two-ton mining ship, chiefs cracked coconuts with bush knives and lit a small fire on the dock’s concrete. As drummers beat rhythms into hollowed-out logs and a man dressed in tī leaves sang chants of welcome in Cook Islands Māori, the captain and crew of the specially refitted vessel, the Anuanua Moana, proceeded down the gangway and onto the dock. Women garlanded them with vines harvested on long hikes over jagged coral. In a few weeks, the Anuanua Moana would set off on a research expedition, pursuing minerals used in electric vehicle batteries and other technologies widely viewed as essential to the transition away from fossil fuels. Never before have these minerals been commercially mined at the depths targeted by the Anuanua Moana.

Dignitaries observed the formalities from beneath a pop-up tent. Among them was Prime Minister Mark Brown. “It’s a really important day,” he said. He described the Anuanua Moana as a symbol of “the future prosperity of our country” and noted proudly it is “rare for an exploration vessel of this kind to be based in the South Pacific, let alone in the Cook Islands.” Indeed, the ship had traveled from Galveston, Texas, to a tiny country 2,000 miles east of New Zealand that is home to fewer than 15,000 residents, a journey of some 5,500 miles. In a country where the speed limit is 25 miles per hour and pretty much everyone has a relative in common, the Anuanua Moana quickly became the talk of the town.

Scientists worldwide counter that the disruptions to ocean ecosystems and food chains could be catastrophic.

The Anuanua Moana belongs to Moana Minerals, a company registered in the Cook Islands but wholly owned by Ocean Minerals Limited, a Texas-based offshore mining company pursuing deep-sea minerals. A local schoolgirl named the ship in a contest: Anuanua Moana translates as Rainbow Ocean and references the symbol of hope that God sent to Noah after flooding the world to rid it of perdition. Equipped with sonar, grabs, corers, hydrophones, sensors, cranes, three laboratories and a remotely operated underwater vehicle, the vessel will collect samples of minerals to determine what riches Cook Islands’ seafloor might contain. The bottom of the ocean is littered, to varying density depending on where, with polymetallic nodules — baseball-sized rocks containing minerals such as cobalt and nickel used to make lithium-ion batteries. The most valuable concentrations appear in the Pacific Ocean.

Scientists discovered deep-sea minerals more than a century ago, but only recently have conditions coalesced to justify a deep-sea mining industry. First came the heightened awareness of the climate crisis and the ensuing Paris Accord, with its target of keeping temperatures from rising more than 1.5 C from pre-industrial levels. Then came the ramp-up of renewable energy technologies, increasing demand for minerals necessary to deploy them, which today are often sourced from war-torn countries and China. With deep-sea minerals finally worth enough to warrant the enormous cost of commercially extracting them, mining companies claim their effort is humanity’s only hope to escape the scourge of climate change. Scientists worldwide counter that the disruptions to ocean ecosystems and food chains could be catastrophic.

There is an irony to this. The purported solution to climate change, and any associated environmental and social costs, will require sacrifices by tiny island nations that produce negligible carbon emissions and will be disproportionately affected by rising sea levels and warming oceans.

Ocean Minerals and other companies are partnering with governments with dominion over large areas of ocean, including the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga, which control waters the size of Mexico, India, Poland and Afghanistan, respectively. All are island nations with limited means of generating revenue beyond tourism, fishing, agriculture and, in Nauru, a detention center for people seeking asylum in Australia.

COVID-19 placed the need for diversification of their economies into high relief. In March 2020, the Cook Islands government, which markets the country as “a little paradise,” sealed the country’s borders. The tap turned off overnight. Aid from the Asian Development Bank and New Zealand’s government sustained those who had worked in tourism; the rest ate what they could harvest from land and sea. Throughout the Pacific region, governments quickly realized the extent to which their economies revolved around visitors. For decision-makers in nations with nodules, deep-sea mining became an increasingly attractive option. Leaders began speaking publicly about the minerals’ potential to energize their economies while helping to wean the world off fossil fuels.

The data the three companies will gather over the 250,000-square kilometers they have been collectively allotted in the Cook Islands will inform the government’s decision on whether to license actual mining.

In February 2022, the Cook Islands reopened to visitors, and the government licensed three companies to explore its waters for minerals: Moana Minerals, whose parent company, Ocean Minerals, is run by a South African diamond miner; CIC Limited, a subsidiary of the Florida-based Odyssey Marine Exploration, which before turning to deep-sea minerals was in the business of diving for sunken treasure; and a joint venture of the Cook Islands government and Global Seabed Resources, a Belgian company known for developing a deep-sea “nodule collector” called Patania II. At a ceremony held to celebrate the awarding of licenses in February 2022, Prime Minister Brown described mining as “an enormous step in our transformational journey towards a sustainable and thriving future.”

The licensed companies moved quickly. They installed offices and local managers on Rarotonga, where “town” constitutes a movie theater, a courthouse, a police station, some stores and cafes, and a nightclub (all closed on Sundays). Their presence was noticed. Two jovial Cook Islanders known as the “aunties,” who frequently feature in marketing materials produced by the country’s tourism bureau, Cook Islands Tourism Corporation, appeared on YouTube discussing seabed minerals.

“What do you know about these rocks?” one woman, holding what looks like an ordinary stone the size of a tangerine, says to the other.

“I know everything about that rock. You know, that rock is a nodule.”

“Oh, a noodle?”

“Nodule. You can find them about four kilometers deep in the ocean…They have a lot of different elements in them, like minerals.”

“In here?”

“Yeah. Cobalt, copper, manganese, titanium, yeah. Valuable rare earth elements in there.”

“Those are big words. Speak English, e koe [you].”

The informed aunty explains that the minerals are used to make phones and electric cars, like the one “our friend Mark Brown” drives.

“Know how our country relies on tourism? We need to have something different. We need to help our economy. So that’s what the government is doing.”

During month-long expeditions expected to cost US$100,000 per day, Anuanua Moana and Seasurveyor, a 39-meter catamaran owned by CIC Limited, which received an equally warm welcome, will be collecting nodules within their assigned areas to build a picture of the benthos in the country’s exclusive economic zone, the offshore area that it alone may exploit.

“We’re able to see where their samples were taken, and then attached to that is the attributes of those samples,” said Rima Browne, a young Cook Islander who works as the senior knowledge management officer at the Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA), the branch of the Cook Islands government set up to regulate deep-sea mining. The data will reveal the density of the nodules and help lawmakers better understand the impacts of mining them.

While the government has access to some historical data collected during surges of interest in seabed minerals between the 1970s and 1990s, little is known about the deep sea in the Cook Islands — or anywhere else. This is the primary point scientists worldwide are pressing: we don’t know a lot about the ocean floor — the surface of the moon is more accurately mapped — and the consequences of mining it could be either manageable or disastrous.

The data the three companies will gather over the 250,000-square kilometers they have been collectively allotted in the Cook Islands will inform the government’s decision on whether to license actual mining. (It will also, Browne explained in an interview, contribute to Cook Islands-specific curricula in schools, where the geology and history of New Zealand, which controlled the country from 1901 to 1965, are now taught.)

Opponents of mining are suspicious of contracting data collection and testing to companies with a vested interest in the habitat and activity they’re studying. They are also concerned that investments in exploration come with expectations of permission to mine. Mining companies and the SBMA respond that data is data and data is good and planning is proceeding with a sense of precaution that’s never preceded an extractive industry.

Other scientists, including more than 700 marine science and policy experts from around the world who signed a petition advocating for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, believe that the impact will be difficult to predict but wide-ranging and irreversible.

“[Mining] needs to be done sustainably, and we know that that’s the wishes of our people,” said Derek Johnson, director of licensing and compliance at SBMA. “They do want to see us being able to take advantage of some of these resources, but not at any cost. And that’s why we’re very strong in our approach to our regulation and the enforcement of our regulations.”

He described rigorous environmental management plans companies will have to submit and said the government will install an observer on every mining vessel.

“But they will do what they like underwater because you can’t see it,” countered Imogen Ingram, who holds a chiefly title on Rarotonga. She explained that enforcing deep-sea mining regulations would be like enforcing fishing regulations, except worse. While the government monitors fishing vessels from faraway countries using satellite technology and observers on boats, prosecuting illegal behavior at sea is another story. It takes the country’s lone police boat days to reach the northern border, and by the time it gets there, offenders have already left.

Enforcing regulations at sea is complicated, time-consuming and expensive. So, too, is drafting them. The International Seabed Authority, the agency the United Nations tasked as gatekeepers of the seabed located outside of territorial waters, planned to determine regulations for mining in international waters at its meeting in July, but the tough decisions were postponed to 2024. The Cook Islands passed legislation in 2017 that declared its entire exclusive economic zone a marine-protected area, but other than a ban on industrial activity within 50 nautical miles of any shore to protect locals’ fishing grounds, the area remains unzoned.

To make the point that conservation and mining can coexist, so long as the area is carefully managed, the government cites a scientific literature review authored by Gerald McCormack. A zoologist by training and former director of the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust, which records species in the Cook Islands, McCormack sees mining as having “the least environmental impact of any industry I can think of.”

According to McCormack, the country’s deep sea is a biological desert, and mining will have a minimal impact. Other scientists, including more than 700 marine science and policy experts from around the world who signed a petition advocating for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, believe that the impact will be difficult to predict but wide-ranging and irreversible. They raise questions about carbon stored in the seabed’s sediment being released to further heat the planet, and the introduction of heavy metals, disposed of after processing, into food chains that reach humans.

In the Cook Islands, where dinner is often pulled out of the sea that day and per capita GDP is below Thailand’s and Libya’s, the risk of fouling the environment is closely felt. “I mean, this thing is so emotive,” McCormack said. “Science is out the window. Nobody actually cares a damn about the science. People only care about the bits of science that agree” with their stance on mining, he said. “The community is being split.”

On this last point, McCormack is right. Some Cook Islanders look forward to the funding the government says mining will bolster health care, education and a higher standard of living in a country where many of those who leave to pursue post-secondary education don’t come back. They say that the wealth generated by mining will help the country prepare for the impacts of climate change.

Others find these ideas romantic. They cite examples of current and past corruption that make them wary of the government’s current slew of promises. They don’t trust that their country will be amply compensated by mining companies, or that the government will responsibly spend whatever does come. They highlight alternative routes to economic development such as training for employment in Internet-based industries for remote work.

How the government ultimately decides on the issue of mining will depend on the data collected, but also on a complex interplay of popular opinion, a version of cronyism peculiar to small, isolated communities, and the influence of traditional leaders. Many of the latter moonlight as officials of the modern government, and on Rarotonga and its even smaller neighbors, many families include public servants.

“It’s very challenging for you to look after an island … and also at the same time working for government,” said Tangi Tereapii, who is a paramount chief from the island of Mangaia, where his authority exceeds that of the Cook Islands High Court in some matters, and also director of renewable energy programs for the Office of the Prime Minister.

Because of this interconnectedness and for other reasons, including an ingrained deference to authority, what the government says usually goes. “There are subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which they apply pressure,” Ingram said.

“The prime minister came to my island this year … and he said seabed mining will make you millionaires,” added Paul Allsworth, a former auditor who is president of the Koutu Nui, a formal body of traditional chiefs. He remembered being “surprised at the statement.”

Peter Ngatokorua is a retired schoolteacher who lives on Mangaia, 100 miles southeast of Rarotonga. On most days, but not Sundays out of respect for the churchgoing, he steers his wooden canoe, powered by an outboard motor, out of the harbor to fish in a favorite spot. Ngatokorua learned to fish from his elders, and, just as they did a century ago, goes to sea for subsistence. “We rely on it,” he said. “Can’t afford tinned meat nowadays.” He said tuna are getting smaller, and can only be found farther out, in deeper waters.

Peia Patai, a fisher, boat captain and celestial navigator from the island of Mauke, echoed Ngatokorua. “I’ve seen the changes: fish are slowly disappearing,” he said.

Though the explorations of the Anuanua Moana seem far away, Patai and Ngatokorua are likely to feel their impact, for better or worse. What the ship and the others plying the depths of the ocean might do adds to the uncertainty they face resulting from seas warming, storms intensifying and ocean biomass plummeting. The fear many scientists, activists and fishers articulate is that mining won’t yield anything of value but will destroy the ecosystem supporting the fish islanders rely on.

That’s not a possibility the Cook Islands government seems willing to acknowledge.

“As people of the ocean, we care for our marae moana [sacred ocean] and we take our role as ocean stewards very seriously,” Prime Minister Brown said at the ceremony held to mark the arrival of the Anuanua Moana. “Our ocean connects us, it sustains us and supports us all. We will protect it and we will harvest it.”

This article was developed with the support of the Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism grant program. Raf Custers and Greet Brauwers contributed to the reporting.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.