The End of Canada’s Geographical Naivete

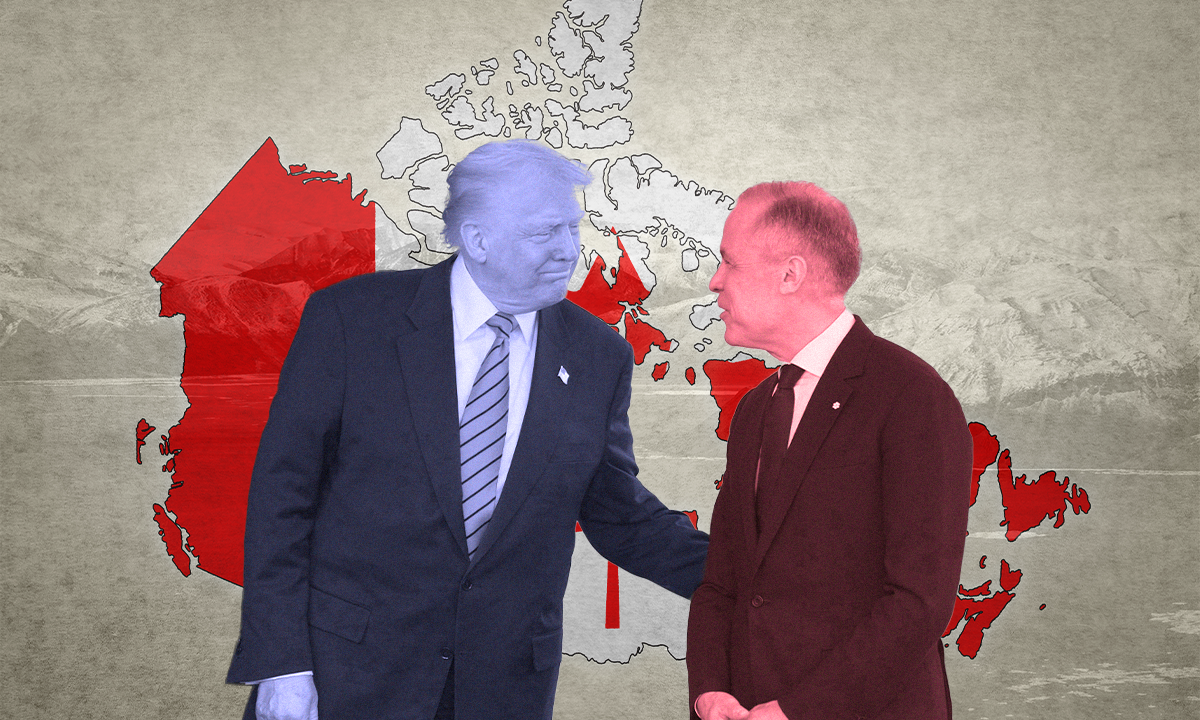

With a threatening and unpredictable U.S. to the south and a mining scramble in the Arctic, Canada confronts a strange new security landscape. U.S. President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney. (Graphic by Truthdig. Images sourced via AP Photo and Adobe Stock.)

U.S. President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney. (Graphic by Truthdig. Images sourced via AP Photo and Adobe Stock.)

Since the conclusion of the War of 1812, the invisible line running between Canada and the United States has been known as “the world’s longest unprotected land border.” Stretching about 5,500 miles (nearly 9,000 kilometers) from the Pacific coast of British Colombia to the Atlantic provinces, it has been defined for many by friendly and orderly passport controls, unmonitored forests and cross-border grocery runs. But as with so much else, those days abruptly ended following the election of Donald Trump. The U.S. president’s rhetoric about conquest, combined with a great power minerals scramble in the Arctic, has ushered in a disconcerting new chapter in Canada-U.S. military relations — one that finds Canada boosting defense spending and anxiously pondering its role in the global security architecture.

It did not take long for a new strategic uncertainty to redefine relations with a country that has long been considered Canada’s closest friend and ally. Freshly elected and meeting with former Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau over Thanksgiving dinner, Trump notoriously quipped about Canada becoming the 51st state. Some dismissed this and other shocking statements about annexing Canada’s three territories and 10 provinces. But many, including Trudeau, took it seriously, and decided it best to err on the side of caution on the question of possible American hostilities.

“For a long time, the status quo in Ottawa was this ‘blessed geographic naivite’,” said Anessa Kimball, a defense specialist with the Centre for International Security in Laval, Québec. “We believed in a benevolent [U.S.] hegemony that would not affect us — that our moral superiority extends so far, and we would be so respected, that nobody would ever bother to consider attacking Canada, because it’s just unthinkable. Canada’s going to have a reckoning it doesn’t want.”

That reckoning is reflected in a spate of new spending on defense infrastructure along the U.S. border. In December, Canada approved $1.3 billion for new fortifications and surveillance tech, followed a month later by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police deployment of two new Black Hawk helicopters to bolster its ability to conduct long distance border patrols. Sixty additional surveillance drones have also been assigned to complement America’s own arsenal of north-facing surveillance towers between northern New York state and Vermont. Symbolizing the new tensions in U.S.-Canada relations, the deployments partly fulfil a new joint “fentanyl strike force” launched in a failed attempt to allay the Trump administration and prevent tariffs.

“Canada’s going to have a reckoning it doesn’t want.”

Despite these novel turns in U.S.-Canadian relations, not everybody is so ready to concede that Canada’s “blessed geographic naivite” has been compromised. “These two militaries have been deeply integrated for a long time,” said Tyler Shipley, an historian at Humber College, at a panel held in April. “The idea that Canada boosting its spending will help it repel an invasion from the U.S., it frankly boggles the mind.” Populist appeals to “elbows out” nationalism and the need to defend against an American threat, said Shipley, is best understood as a political tactic to get Canada to boost its comparatively modest military budget.

If so, it seems to be working. Published in April 2024, Canada’s Our North Strong and Free defense strategy commits $73 billion in new spending over the next 20 years. New weaponry includes armored vehicles from London-based General Dynamics Land Systems, dozens of F-35s, nine CC-30 strategic tanker transport aircraft, 16 Cormorant helicopters, 11 SkyGuardian drones and up to 16 P-8A Poseidon aircraft. The construction of 15 warships, equipped to carry missiles, is also underway in Halifax, dubbed as the “largest shipbuilding project in Canada since World War II.” Replacing Canada’s aging frigates, the project modernizes Canada’s naval fleet to match the rest of NATO.

Just under 2% of Canada’s current defense spending is targeted for its southern border with the U.S. Much of the remainder is for militarizing the vast Arctic, where contested maritime passages and access to critical minerals bring Canadian interests into possible conflict with the U.S., China and Russia.

Canada’s remote and icy Arctic Archipelago, contained in the territory of Nunavut, spans 94 major islands and more than 36,000 minor islands. An ancient and fragmented landmass through which the Northwest Passage carves its wild currents, it begins to change around the 60th parallel, where the landscapes of the mainland become tundra and boreal forests contiguous with those in the Northwest Territories and the Yukon.

For centuries, this region has enjoyed a poetic isolation within Canadian national borders, with a military presence historically limited to a few languid military outposts. The Cold War-era joint venture between the U.S. Air Force and Royal Canadian Air Force known as the Distant Early Warning Line surveillance outposts, or DEW Line, were abandoned in 1993 (with environmental clean-up costs dumped on Canada). Hawkish policy arguments on Arctic militarization, championed by former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, have generally revolved around securing seabed resources and maritime control, and have resulted mostly in Arctic rangers deployed on coastal “sovereignty patrols” and search-and-rescue missions.

In recent months, talk in Washington about Canada’s role as a northern buffer for the U.S. has reignited old arguments about securing the Arctic for its own national interest. This has been punctuated by the announcement of the first northern operational bases in Iqaluit, Inuvik and Yellowknife, intended to “better assert Canadian sovereignty.” Other developments — some explicitly NATO-oriented, others not — include the upgrading of NORAD bases, an expansion of Canada’s fighter jet presence and the construction of a new Arctic satellite ground station. Despite Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok’s repeated criticism of military projects in the Arctic, the Nanisivik Naval Facility, a relic of the Harper era, is again being revived and is now being dragged through stalled rehabilitation. In mid-March, Prime Minister Mark Carney committed $420 million to expanding Canadian Armed Forces presence in the north, as well as a slew of multimillion-dollar investments into Indigenous-owned housing and energy corporations in Nunavut, anticipating growing settlement.

Arctic securitization is not just about protecting the integrity of the littoral far-northern border. It is designed to protect Canada’s role in one of this century’s crucial industries.

As the Arctic warms four times faster than anywhere else on the planet, it is developing into a shipping route for the 15 million tons of rare earth elements estimated to be buried in Canada’s soil, including across the Arctic. In 2022, Canada’s national critical mineral strategy committed $3.8 billion over eight years to the sector’s development. Competition to claim these world-leading reserves have led to a security scramble in the Arctic that was a major concern of the first Trump administration. In 2019, he invoked the Defense Production Act of 1950 to rectify a “shortfall” of rare earth elements. Former U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross stated at the time that the Republicans would take “unprecedented action to ensure that the United States will not be cut off from these vital materials.”

Not everyone sees territorial incursions in the Canadian Arctic as credible.

This determination carried over into Trump’s current term, and was no doubt given new urgency by China’s announcement in April that it was imposing new export restrictions on heavy rare earths.

In December, Canada released an Arctic Foreign Policy paper warning that more mining and maritime traffic through the Hudson Bay and Northwest Passage presents “additional opportunities for foreign adversaries and competitors to covertly or overtly operate in the Canadian Arctic.”

As with concerns over U.S. intentions on Canada’s southern border, not everyone sees territorial incursions in the Canadian Arctic as credible.

“We’ve had to inflate the threat in the Arctic to get Canadians to invest in the military,” said Stephen Saideman, director of the Canadian Defense and Security Network and Paterson Chair in International Affairs at Carleton University. Russians have been focused on “their own side of the Arctic,” he said, while boots-on-the-ground occupation is untenable for either them or American troops. “Our biggest security problem in the Arctic is the possibility that a cruise ship catches on fire.”

Others argue that Canada has been taking northern security for granted. Rob Huebert, of the right-wing Canadian think tank Macdonald-Laurier Institute, has made this case for years.

“The [Obama] State Department was beginning to restate its position that it views the Northwest Passage as an international strait,” Huebert wrote in 2018, outlining how the Obama administration rejected the Harper government’s calls for an Arctic shipping reporting system. “Given all of Trump’s actions to date, does anyone really believe that he will be willing to continue to look the other way? If transit shipping for the purposes of servicing Alaskan oil development or providing goods for American cities were to begin, does anyone really believe that he will not attempt to assert the American position?” More recently, Huebert stressed the imminent need to “resolve overlapping claims to the extended continental shelves of Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Russia and the United States.”

Northern militarization that ramped up under the Conservative government in the name of Canadian sovereignty was historically criticized as isolationist and detrimental to Canada’s Arctic diplomacy. But, after four Liberal governments turned its back to this agenda, sovereignty returned to overshadow all other issues during April’s snap federal elections. The electoral platform of the New Democratic Party — Canada’s ill-fated social democratic party that has bled popular support since the Liberals were elected in 2015 and lost official party status this election — was anchored by calls for ballasting the domestic economy with a homegrown military-industrial complex.

Arctic relations between Canada and the United States are aggravated by two long-standing territorial disputes. The first involves Canada’s historic claim over the Northwest Passage, which crosses through the Arctic Archipelago, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The U.S. and the EU consider this strategic channel — which cuts global shipping routes in the north by 40% — as an international strait. The Canadians and Americans are also divided over rights to oil-and-gas rich areas of the Beaufort Sea encompassing more than 8,100 square miles (21,000 square kilometers). Whereas Canada cites the authority of treaties between Russia and Britain from 1825 and 1867, the U.S. argues that those extend only to coastlines, and not to deep-sea continental shelves.

In September, a joint task force was established by the Trudeau and Biden governments to resolve the boundary disputes through negotiations, in which the region’s Indigenous authorities have demanded participation. Responding to the accelerating resource and security race in territories where Indigenous communities have asserted cultural and economic interests, sometimes across state borders, Sara Olsvig, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, stated at a U.N. forum in April, “We refuse to be treated as figures on a chessboard of power politics.”

“Trump has declared that he wants to bend the policies of other countries to his will.”

The U.S. is also targeting historic treaties that protect the integrity of Canada’s freshwater ecosystems and drinking water. In his first 100 days in office, Trump has referred to Canadian rivers and lakes as “a very large faucet,” threatening hard-won protections of Canada’s “blue gold” — which ranks among the world’s largest fresh water resources. To this end, his administration is seeking changes to Great Lakes water-sharing agreements, and to the Columbia River treaty to divert water to California. The president’s leveraging of dusty laws from the annals of American history has some on high alert. Several historic agreements — including the Treaty of Paris of 1783 and the Treaty of 1818 — define the international border and demarcate the division across the Great Lakes, a region that provides water to 40 million people in both countries.

“Trump has declared that he wants to bend the policies of other countries to his will,” Maude Barlow, renowned Canadian activist and co-founder of the Council of Canadians, wrote in the wake of Trump’s election. “We had better be ready.”

With the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement being renegotiated next summer, 85 civil society groups have now signed onto a petition demanding the Canadian government defend these regulations and prevent the privatization of water. Activists are calling for the Canadian government to uphold and strengthen binational agreements including the International Boundary Waters Treaty Act, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, the Columbia River Treaty and Canadian environmental legislation protecting water.

“There is no economy or sovereignty without freshwater,” said Ashley Wallis, associate director at Environmental Defense, referring to Trump’s pressure tactics to access Canadian resources. “Under no circumstances can fresh water in Canada be used as a bargaining chip.”

If Canada were to take the threat of American revanchism seriously, what role would NATO play? Kimball suggests that Canadian security — with both Russia and the U.S. in mind — would be well-served by inviting Swedish submarines to Iqaluit to “patrol and hang around” in a Latvian-style NATO huddle. The defining NATO mission in which Canada has participated in the past decade has been Operation Reassurance, in which Canadian troops supported Eastern European bases on the border with Russia, heading combat, intelligence and transport operations in Latvia. The Canadian military is already stationed in Yellowknife, Whitehorse and Iqaluit, and it routinely conducts exercises around Nunavut as part of Operation Nanook. “If Canada is wise, it would enlarge these bases, permit NATO troops to base there, and then invite our Nordic partners to come to the Arctic,” Kimball said.

This would mark a new relationship with Canada’s NATO allies that are also questioning whether they can depend on American security guarantees that have long defined the transatlantic alliance.

“Canada is now trying to figure out where it’s going to sit in the world.”

“I think it might be better to have a NATO without the United States than with the United States,” Saideman said. “Canada is now trying to figure out where it’s going to sit in the world, when it can no longer trust the United States to have its back.”

Whatever the shakeout for the future of NATO, Trump’s destabilizing impact has left Canada wrestling with what Philippe Lagassé, a professor of international affairs at Carleton University, describes as “a shift in our entire defense culture and worldview.”

“We pivoted from the United Kingdom to the United States after the Second World War,” says Lagassé. “We’re now having to undergo another pivot on a similar scale. We’re not quite sure what that will look like yet. We’ll need to develop an autonomous defense policy, which is something we’ve never done.”

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.