The Demilitarization of the White House

Barack Obama has made a welcome change to the presidency, dropping the praetorian guard that used to flank his predecessor at every opportunity.Barack Obama has dropped the praetorian guard that used to flank his predecessor at every opportunity.

I was struck watching television coverage of President Barack Obama on his Asian trip. On his arrival and departure from the cities he visited, he descended and ascended the landing staircase of Air Force One by himself. When it was raining, he carried his own umbrella. Against a stormy sky, the camera caught an emotionally moving image — a solitary figure sheltering himself from the rain.

Where were the aides and orderlies and protocol people and other staff members who usually surround a high official? How could he be allowed out in the rain by himself, unless he had asked that it be so?

It was something on which I have yet to see public comment: the demilitarization of the American presidency, and the demilitarization of the White House during the first nine months of Obama’s term in office.

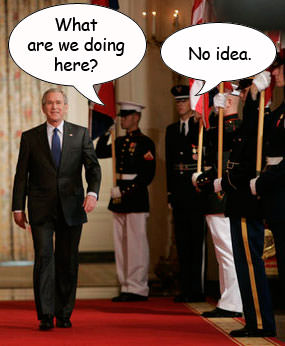

It is a powerful and symbolic change, even if an unconsidered or uncalculated change from George W. Bush. When Bush made pronouncements, television showed him walking the length of a White House hall to the podium. The hall was on important occasions lined by enlisted members of the uniformed services, in dress or duty uniforms, two of whom would step out to flank the door behind him and frame him personally. He was nearly always accompanied by a commissioned aide de camp, standing to the side as the president spoke. (Possibly the aide was the one who accompanies the president, carrying the nuclear codes; but that would seem an excess inside the White House.)

When President Obama makes a declaration to television and the press, he more often than not walks outside unaccompanied.

It is not just that Bush liked uniforms and military folderol, having deliberately foreshortened his own experience of them in the Texas Air National Guard, so as to be spared the onerous experience of active duty in the war then going on.

We also know that he constructed his administration in many of its more deplorable aspects on the foundation of his claim to be “a war president,” just like Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, possessing in his sole person the totality of the power of the “unitary executive” of American government — a subversive doctrine, if there ever was one, and one that should be, but probably won’t be, struck down by the Supreme Court at its first opportunity.

The idea of being a war president pleased the little boy in him, and probably was his unconscious or repressed compensation for having been a slacker in the Vietnam War, just like his vice president, Dick Cheney, and his predecessor, William Jefferson Clinton, but unlike his naval hero father, George H.W. Bush.

The younger Bush was very good with his smart salutes in response to those of the Marines welcoming him or taking leave of him when he used his Marine Corps helicopter. Had he thought of it, he probably would have ordered up a naval bosun’s mate to whistle him aflight and aground.

The Marines saluted as salutes are meant to be employed.

They are an act of deference or respect of a military person to his superior when addressing, or being addressed by, the latter, or in acknowledging an order, or in taking leave of the superior, or in simple greeting to a fellow officer, who may in turn salute in acknowledgment.

There is a certain amount of rigamarole in various services or regiments or national armies as to whether you salute indoors as well as outdoors, or unhatted as well as hatted. The one universal rule is that civilians do not salute military officers. An American civilian acknowledges a military person’s salute with a nod or smile, and, instead of saluting, places his hand on his heart when the national anthem is played. Obama seems to respect this protocol.

It was Ronald Reagan who started presidential saluting. No doubt it was a glamorous reflex going back to his “military service” in Hollywood.

As the historian John Lukacs has written, this revealed a profound change in the American national consciousness. An unwarlike patriot, whose thoughtless good instincts were constructively matched with the personally dangerous reformism of Mikhail Gorbachev, Reagan had a lot to do with making the end of the Cold War possible. But he also formalized the evolution of the American nation from the peaceful and isolated society of before 1941 to the militarized Cold War nation it had become by Reagan’s time, and thereafter remained.

There was a wonderful exhibition of paintings that toured internationally in 2007 displaying the eminences of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, showing Louis XVI, George III, Ferdinand VII of Spain and Pope Pius VII, all with the accouterments and conventional symbols of power, status and remoteness: the pope on his throne; Ferdinand in royal costume with his orders, royal baton in his hand; George III similarly attired in ermine robe and crown and with scepter beside him.

In sober contrast there was a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington standing in a plain black suit. Next to him is a sheathed sword. His hand touches a document on the table next to him, possibly the Constitution, and a small republican shield ornaments the chair.

This was what it had been all about, to create an American presidency, in a plain suit and with a sheathed sword. Barack Obama as candidate promised to be a president of peace. We may hope that he will so be.

Visit William Pfaff’s Web site at www.williampfaff.com.

© 2009 Tribune Media Services, Inc.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.