So, About That Severed Ear …

A marvelous new biography of Vincent Van Gogh asks what if it was untreatable epilepsy that drove him mad, he didn't cut off his lobe for a woman and he was killed by delinquents rather than committing suicide?

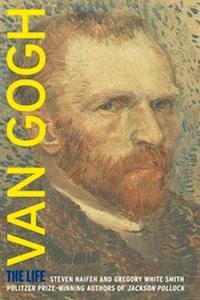

“Van Gogh: The Life”

A book by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith

Everyone knows Vincent Van Gogh’s history — the mad, suffering genius who cut off his ear for a prostitute and committed suicide in a cornfield with circling crows. But what if the stories are pure Hollywood?

Even on the cover, this marvelous new biography invites us to question our assumptions. Its title, a definitive-sounding “Van Gogh: The Life,” is printed on a translucent paper skin, through which filters a hazy self-portrait. To really see the artist, we must peel back the outer layer, finding the painting underneath. To follow their Pulitzer Prize-winning “Jackson Pollock,” Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, two Harvard Law School graduates, have spent 10 years reinvestigating the life of Van Gogh: the facts and the factors — hereditary, historical, sociological and cultural — which produced an artist whose work, like Pollock’s, is today worth untold sums. The resulting 900-page biography reads like a novel, full of suspense and intimate detail. Their accompanying website, still incomplete, promises images for every artwork described, contains a huge (if somewhat unsearchable) bibliography and provides unexpectedly fascinating research notes. We can almost hear the authors debating: Do we trust this witness? Was Van Gogh a victim or a perpetrator? Or both?

Van Gogh accurately perceived that forces outside his volition provoked his unrelenting cycles of rage, depression, intense anxiety, sudden despair and incomprehensible terror. He had temporal lobe epilepsy, a genetically influenced physical disorder that causes constant alternations between aloof withdrawal and overwhelming anger, irritability and dejection, self-denial and extravagance, religious ecstasy and sinner’s guilt. He tried to banish his demons through bizarre acts of discipline and self-mortification, punishing himself with fasting, exhaustion, heat and cold, sleeping uncomfortably on his walking stick, then flogging himself with it. When nothing worked, he consoled himself with alcohol and prostitutes, ending up paranoid, hallucinatory and impotent.

Van Gogh’s pathological nonconformity and constant job failures overwhelmed a well-meaning family haunted by suicides and mental illness. Casting himself as the prodigal son, he unhesitatingly manipulated his stony, Protestant clergyman father, his “melancholy” mother and his brother, Theo, using emotional and economic blackmail. At last, when Vincent was 27, delusional, unemployed and unemployable, his father attempted to have him committed to a mental asylum. Vincent fled.

Finally he discovered art — one of his few remaining “social graces” encouraged by his family. Too eccentric for art school, he took a learn-to-draw course at home, obsessively repeating its exercises throughout his career until he died, nine years later. Having failed at teaching and preaching, desperately lonely, yet incapable of empathy, he fantasized that art would establish a durable connection — bring him a family, a community of artists, a woman or a friend with whom to live and share everything. Van Gogh’s letters predicted both his disastrous personal relations and his enduring artistic glory.

Exploring widely different styles, but always utterly original, Van Gogh created passionate, “heartbroken” artworks — “abstractions” where image, rhythm, color and texture all come together to express his emotions.

When fame finally came, it was caused by the scandal of Van Gogh’s severed left earlobe. Smith and Naifeh believe that Paul Gauguin was the intended recipient of the earlobe, and that he tried to use his turbulent relations with Van Gogh to get personal publicity. He conspired with another artist, Emile Bernard, to suggest to a journalist, Albert Aurier, that Van Gogh had physically threatened Gauguin. But their plan backfired. Aurier focused his article entirely on Van Gogh, describing the insane act that put the artist, his brain “at a boiling point,” into an asylum where, in isolated confinement, he created works of “demented genius.” Suddenly Van Gogh was a hero. What the authors call “Aurier’s baser tabloid fascination with Vincent’s abhorrent, criminal or lunatic behavior” saddled Van Gogh with the stereotypes that reign today. Aurier’s article also made his own reputation. He had single-handedly discovered a major artist and knew exactly how to sell him.

|

To see long excerpts from “Van Gogh” at Google Books, click here. |

But it was too late. Within weeks, Van Gogh lay dying of a gunshot wound. Naifeh and Smith carefully review the evidence and conclude that Van Gogh almost certainly did not commit suicide. He was shot in a courtyard, not in a field, injured, probably accidentally, by harrying adolescents. Although the bullet came from an improbable angle, and from too far away, Van Gogh claimed, “I wounded myself,” so the boys would not be blamed. “Do not accuse anyone. It is I who wanted to kill myself.”

As the authors appeal Van Gogh’s case, all our stereotypes are questioned. What if untreatable epilepsy drove him mad, he didn’t cut his ear to impress a woman and he was shot by delinquents? Will the Van Gogh industry — exhibitions, scholarly books, coffee mugs, rock songs — survive? In beautiful prose, Naifeh and Smith argue convincingly for a subtler, more realistic evaluation of Van Gogh, and we all win.

Julia Frey’s “Toulouse-Lautrec, A Life” was a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist and won the Pen West Literary Award in nonfiction. Her latest book, “Balcony View — a 9/11 Diary,” is out this month.

©2011, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.