Sticky Fingers

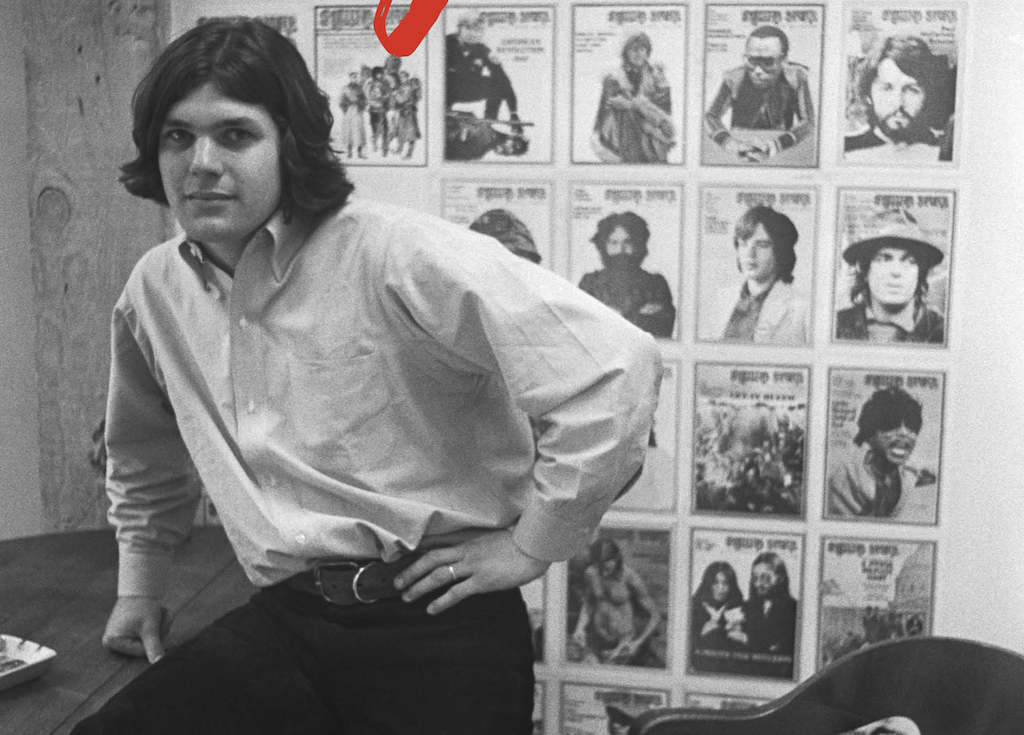

A nearsighted new biography of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner would have us believe that any narcissistic cokehead could have shepherded innovative work by Hunter S. Thompson, Annie Leibovitz and others just by being in the right place at the right time. Founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine Jann Wenner on the cover of Joe Hagan's "Sticky Fingers." (Penguin Random House)

Founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine Jann Wenner on the cover of Joe Hagan's "Sticky Fingers." (Penguin Random House)

“Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

A book by Joe Hagan

One day several years ago in Rhinebeck, New York, Jann Wenner, the founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine, took his neighbor, Joe Hagan, a contributor, out to lunch to talk about writing Wenner’s biography. Wenner had tried this before. Two previous biographers had quit over the usual tensions: control, access, final approval. To Hagan, Wenner promised access to a bulging archive of letters, familial support and profuse cooperation. Hagan quickly learned that writers would gleefully slam Wenner over abuses, broken promises and stiffed payments. For 50 years, Wenner had pissed off enough people to make Hagan’s 560-page “Sticky Fingers” a cocaine-soaked bitch-fest on a bender, the kind of book that seldom earns out its bidding war among publishers. Because the Wenner Media empire once spanned the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, Outside magazine and the dishy Us Weekly, he’s the mogul-monster people love to bash.

When Hagan finally shared his galleys with Wenner last summer, the inevitable falling out recurred, and Wenner withdrew his support in a gambit that had only an upside for Hagan: the word “tawdry” attached itself to his life story, goosing sales for a slimy tell-all. (Or, as Hagan says, “Wenner’s supersized success supersized his cheapness.”) In this tabloid era, such titles barely cause a blip, since everybody has heard many of these stories and assumed the rest. But suppose Hagan had adopted a stronger point of view: the story of Wenner the journalist, winner of two Polk Awards in this decade, the first to successfully steer alternative reporting toward rock music’s raucous, eccentric moods? Instead, the Wenner we meet in Hagan’s narrative seems barely capable of editing a sentence. Even his detractors find themselves disparaging “Sticky Fingers,” which reduces the man’s charm and conceits into cliche, even though his importance ranks with (Sun Studio’s) Sam Phillips or (Motown’s) Berry Gordy.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Sticky Fingers” at Google Books.

Hagan started work before Sabrina Erdely’s discredited 2014 account in Rolling Stone of a University of Virginia gang-rape, when editors inexplicably skipped their fact-checking. Wenner’s fortunes have suffered since then, and his empire tilted downward just enough to loosen spiteful tongues. These quotes go down in great sleazy gulps, like they do in “You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again” (1991) by Julia Phillips or “Final Cut” (1999) by Steven Bach. But you can’t reconcile Hagan’s Wenner with the editor who oversaw milestone pieces on Altamont or Patty Hearst or Karen Silkwood or Gen. Stanley McChrystal; in Hagan’s eye, Wenner’s life comes off as a series of lucky breaks, as if any narcissistic, cokehead philanderer could have overseen innovative work by Hunter S. Thompson, Annie Leibovitz, Greil Marcus, Ellen Willis, and Matt Taibbi simply by being in the right place at the right time.

Hagan’s text resembles those Albert Goldman doorstops on Elvis Presley and John Lennon, where facts rob attention from a larger truth. Magazine editors piss off a lot of people, and Wenner takes pride in how he aimed his lifestyle straight toward the Kennedy cocktail circuit (Hagan suggests Wenner actually put the moves on a teenage Caroline, who calls him “the Jimmy Buffett of winter.”) Those contradictions can provoke a writer deeper into their subject; instead Hagan churns a conveyor belt of petty duplicities. Even if most of it turns out to be true, it doesn’t shed any light on the culture or its values, any more than plastering David Cassidy bare-chested on a magazine cover improves his music.

In a typically cliched construction, Hagan says the rock culture in Wenner’s pages “cornered the market on Truth with a capital T. … He reinvented celebrity around youth culture, which equated confession and frank sexuality with integrity and authenticity.” But even by 1967, when Wenner put John Lennon on his first issue, rock culture embraced a shifting tension between immediacy and endurance; hot flashes had their place, but Hagan has a slim grasp of how Wenner did more than catch the music’s giant wave—what we now dismiss as “classic rock.” To Hagan, it’s all reduced to celebrity coverage.

Wenner’s success had as much accidental chemistry as, say, Mick Jagger bumping into his schoolmate Keith Richards holding his Chuck Berry album, or both of them chancing upon Andrew Loog Oldham (their influential manager). A number of planets had to align for that chemistry we know as “the Rolling Stones,” and history puts a fated gloss on such events. But like Elvis Presley and Sam Phillips, or Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy, all these figures invented rock culture inside the maelstrom. That vivid sense of adventure and daring goes missing here.

As early as Wenner’s coverage of the Rolling Stones 1969 Altamont concert, he wielded more intelligence than anything Hagan seems to notice. Wenner sent 14 reporters, more than any other publication.

Rolling Stone’s account survives as the definitive journal of that event, and still gets assigned at journalism schools. But you won’t find many quotes from that issue in Hagan’s book. Nor will you find a sentence concerning the “Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” which Jim Miller edited in 1979. That oversized, plushly designed critical compilation still anchors our view of rock history, and Hagan lists it simply as a profiteering gambit.

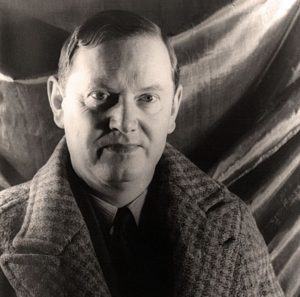

Like a junk-food banquet, Hagan gathers a feast of trash-talk among elites: Keith Richards on Wenner and Jagger: “They’re both very guarded creatures. You wonder if there’s anything worth guarding.” John Leonard on gonzo political writer Hunter S. Thompson: “Thompson, compulsive innocent, is higher on morality than anything else he smokes or drops.” Truman Capote would later say Wenner “thinks like a water moccasin.”

Casting Wenner as a simplistic sellout reduces his accomplishment, and the music he covered, all at once. Publishing a magazine depends on celebrity covers and pinning the zeitgeist to sell product; that’s how Wenner supported decades of rock criticism and progressive politics. Hagan compiles decent reporting, but he also steers sentences into the ditch on every other page: “They were all card-carrying members of New York’s café society, perfect for the collision of socialite ennui and rock-and-roll decadence being husbanded by Ahmet Ertegun, the gentleman hipster of Atlantic Records who ran in the same Manhattan circles as Capote and whose wife, Mica, was an interior decorator aspiring to Park Avenue respectability.”

“Sticky Fingers” finds its reverse image in HBO’s four-hour documentary, “Stories From the Edge,” directed by Alex Gibney and Blair Foster (who share such credits as “Janis: Little Girl Blue” [2015] and “Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown” [2014].) This repositions Wenner’s halo while recycling familiar concert footage from Hendrix, the Stones, and the Clash sprinkled with Thompson quotes, the Rev. Jimmy Swaggart, and segments on the Pulitzer trial. Most of the concert footage comes from familiar settings like the Monterey Pop Festival, but a long sequence on Tina Turner enhances her importance like few others. (Hagan skips another choice quote from the original RS story on the Turners from 1971: “Ike showed his refurnishing job off to Bob Krasnow of Blue Thumb Records one day last year, and Krasnow remarked: ‘You mean you actually can spend $70,000 at Woolworth’s?’ wrote Ben Fong-Torres.) Star photographer Annie Leibovitz goes through old prints with Wenner almost as if they hadn’t invented new vistas of sexual complication.

Perhaps Jann Wenner’s story chewed up at least two “official” biographers before corrupting its third; it’s tempting to guess that he wanted a biographer far more than he wanted any biography. But that would make Wenner almost as naive as “Sticky Fingers” portrays him, and Hagan squanders enough reader trust to give you pause.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.