Wrestling With His Angel

The second volume in Sidney Blumenthal's biography of Abraham Lincoln's political evolution follows the president during the stormy period between the Mexican War and the Civil War. Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

| To see long excerpts from “Wrestling With His Angel” at Google Books, click here. |

“Wrestling With His Angel 1849-1856: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II” A book by Sidney Blumenthal

Reviewed by Allen Barra

Historian Steven Hahn, writing last May in The New York Times on the first volume of Sidney Blumenthal’s political life of Abraham Lincoln, “A Self-Made Man,” said that Blumenthal’s next volume on Lincoln “might serve as a vital hub around which new perspectives on the 19tth century could be devised. This is possible. … But I have my doubts.” Hahn and other historians who seemed to be searching for reasons to belittle Blumenthal’s achievement must now dispel their doubts.

The most written-about human being in history has had the greatest body of literature about him emerge in the last 25 years. Garry Wills’ “Lincoln at Gettysburg” (1992), Doris Kearns Goodwin’s “Team of Rivals” (2005), and James McPherson’s “Tried by War: Lincoln as Commander in Chief” (2009) concentrated on particular aspects of Lincoln’s career. The greatest single-volume biography, David Herbert Donald’s “Lincoln” (1995), focused on Lincoln’s personal life. All are indispensable.

Wrestling With His Angel 1849-1856: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Wrestling With His Angel 1849-1856: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II

Purchase in the Truthdig BazaarBlumenthal is the first historian to define Lincoln solely through his political evolution. “Wrestling With His Angel 1849-1856” — the title is taken from Genesis 32, in which Jacob wrestles all night with an angel — places Lincoln squarely in the storm of U.S. politics between the Mexican War (which ended in 1848) and the Civil War that resulted from the struggle over whether the vast new tracts of territory won from Mexico should allow slavery.

The author takes a daring chance that could not be taken in a standard biography: Lincoln is scarcely mentioned in nearly the first third of the book. When he finally emerges, it is not like Athena springing fully formed from the head of Zeus. The political Lincoln was forged by adherence to the ideals of Henry Clay, the senator from Kentucky and secretary of state, who was Lincoln’s “beau ideal of a statesman”; Lincoln attended one of Clay’s speeches “lying on the ground and listening for two hours as he whittled sticks.” Another powerful influence was Massachusetts senator and twice Secretary of State Daniel Webster, “the most eloquent orator of his age, already immortalized for famous addresses against [Sen. John C.] Calhoun and his states’ rights acolytes.” As the end of the decade approached, Calhoun, who had done so much to create the atmosphere that would lead to war, moaned as he lay dying, “The Union is doomed to dissolution, there is no mistaking the signs.”

Lincoln’s rise is measured against and contrasted with Sen. Stephen Douglas of Illinois, “the most racist state in the North,” and Jefferson Davis, senator from Mississippi, secretary of war under Franklin Pierce, and, finally, president of the Confederacy. “The parallel lives of these two men,” Blumenthal writes, “would define Lincoln’s.”

Jefferson Davis is seen in a new and sharper focus than even in William C. Davis’ 2016 biography, “The Man and His Hour,” and it’s hard to see him in retrospect as anything but a sinister and destructive figure. Called “the autocrat of the cabinet” by The New York Times, Davis increased the size of the standard army by 30 percent and appointed West Point graduates as officers for new regiments in the federal army. He helped develop new, more deadly weapons. Far from all his admirers were Southerners; they included his president, Franklin Pierce, and “a promising West Point-educated young lieutenant … George Brinton McClellan … [who] proudly considered himself one of Secretary Davis’s star protégés.”

With an eye for the kind of detail that makes “Wrestling With His Angel” fascinating reading, Blumenthal relates the story of an executive who refused to pay Lincoln after a court case, “regarding him as too lowly to receive a princely sum.” The executive was the above-mentioned George B. McClellan, the man who Lincoln would later entrust with command of the Army of the Potomac, and then relieve from his post for lack of aggressiveness.

Davis did a great deal more than lead the Confederacy: He helped create it. “From the moment he took office, the secretary of war waged political warfare against Southern Unionists. … By mid-1853, Davis and his Southern Rights faction had gained control of the state [Mississippi] Democratic Party.” And “Jefferson Davis’s control of federal patronage tilted in favor of Southern Rightists.”

Stephen Douglas did almost as much as Davis to bring the country to war, or as one Douglas critic phrased it, “We have found another northern man with strong southern feelings.” Douglas “never uttered an anti-slavery sentiment in his life. … He took no moral stand whatsoever.” Or stated another way, “Slavery was not a moral question at all, he insisted. It’s simply a matter like ‘horse stealing or anything else’ to be decided by popular sovereignty. …” So openly racist was his everyday speech that William H. Seward told him, “Douglas, no one who spells Negro with two g’s will ever be elected President of the United States.”

Lincoln had debated Douglas numerous times since 1838. But senator Douglas commanded a national stage, while Lincoln left public office in 1849 after his first term in Congress. In 1854 he came up against him again on the subject of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which made possible the extension of slavery to the West.

Lincoln “constantly measured himself against Douglas,” and in his own eyes, he constantly came up short: “Twenty-two years ago Judge Douglas and I first became acquainted. We were both young then; he a trifle younger than I. Even then, we were both ambitious; I, perhaps, quite as much so as he. With me, the race of ambition has been a failure — a flat failure; with him it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation; and it is not unknown, even, in foreign lands.”

A friend of Lincoln wrote, “Mr. Douglas’s great success in obtaining place and distinction was a standing offense to Mr. Lincoln’s self-love and individual ambition. … He was intensely jealous of him [Douglas]. And longed to pull him down, or outstrip him in the race for popular favor. …”

Despite Lincoln’s best efforts in seven speeches, the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed, and “In a stroke, the old order cracked apart. All that had been proclaimed to be permanent shattered into pieces; everything settled became undone.”

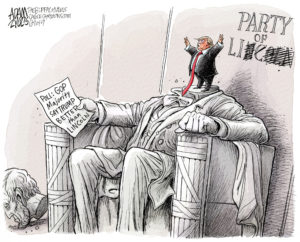

The old Whig party, unable to proclaim itself either for or against slavery, lost the support of pro-slavery Southerners to the Democrats. In the North, a new party began to emerge, pulled together from disparate elements with one thing in common: hatred of slavery.

(The Whig party began in 1835, its popular base forming largely in reaction to the populism of Andrew Jackson, particularly his forced removal of Indians in the South. It favored the power of Congress over the president and also a progressive program in banking and economics to stimulate the economy. The Democrats were Jacksonian populists whose catchphrase was “the sovereignty of the people”; their general principle for governing was majority rule.

The Whigs began to split on the issue of slavery in territories acquired in the war with Mexico. The majority of Whigs in the north were opposed to slavery and moved inexorably to the new Republican Party, which was unambiguously anti-slavery. The Whigs dissolved in 1854.)

As 1860 approached, “Both parties, i.e. the Democrats and the Whigs, had lost their equilibrium.” Lincoln, originally a Whig, was finding common ground with different groups and received unexpected support from Republicans. He was bolstered by his wife Mary Todd, the true founder of “Our Lincoln Party,” and began a sudden meteoric rise that would eventually see him eclipse first Douglas and then Jefferson Davis.

But that is the story for the third and final volume. For now, we are left with Blumenthal’s judgment that “when Lincoln proclaimed himself as a Republican … it was among the most significant events in the coming of the Civil War.”

Blumenthal, probing the cracks and eddies of American history, politics and culture before 1854, has produced a masterwork. It is a tour de force, where none was expected, in the life of a man whom everyone thinks they know. But the Lincoln revealed here is discovered for the first time in “Wrestling With His Angel.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.