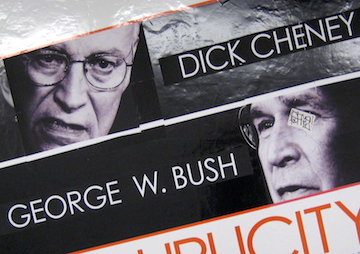

Should George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Others Be Jailed for War Crimes?

We need a full and public accounting of the CIA’s activities, the doings of military and civilian agencies and outfits, the White House’s drone assassination program, and the illegal, devastating invasion and occupation of Iraq. David Poe / (CC BY-ND 2.0)

1

2

3

David Poe / (CC BY-ND 2.0)

1

2

3

But there’s a question that can’t help but arise: What’s the point of bringing such old men to trial four decades later? How could justice delayed for that long be anything but justice denied?

One answer is that, late as they are, such trials still establish something that all the books and articles in the world can’t: an official record of the terrible crimes of Operation Condor. This is a crucial step in the process of making its victims, and the nations involved, whole again. As a spokesperson for CELS told the Wall Street Journal, “Forty years after Operation Condor was formally founded, and 16 years after the judicial investigation began, this trial produced valuable contributions to knowledge of the truth about the era of state terrorism and this regional criminal network.”

It took four decades to get those convictions. Theoretically at least, Americans wouldn’t have to wait that long to bring our own war criminals to account. I’ve spent the last few years of my life arguing that this country must find a way to hold accountable officials responsible for crimes in the so-called war on terror. I don’t want the victims of those crimes, some of whom are still locked up, to wait another 40 years for justice.

Nor do I want the United States to continue its slide into a brave new world, in which any attack on a possible enemy anywhere or any curtailment of our own liberties is permitted as long as it makes us feel “secure.” It’s little wonder that the presumptive Republican presidential candidate feels free to run around promising yet more torture and murder. After all, no one’s been called to account for the last round. And when there is no official acknowledgement of, or accountability for, the waging of illegal war, international kidnapping operations, the indefinite detention without prospect of trial of prisoners at Guantánamo, and, of course, torture, there is no reason not to do it all over again. Indeed, according to Pew Research Center polls, Americans are now more willing to agree that torture is sometimes justified than they were in the years immediately following the 9/11 attacks.

Torture and the U.S. Prison System

In a recent piece of mine, I focused on Abu Zubaydah, a prisoner the CIA tortured horribly, falsely claiming he was a top al-Qaeda operative, knew about a connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda, and might even have trained some of the 9/11 pilots. “In another kind of world,” I wrote, Abu Zubaydah “would be exhibit one in the war crimes trials of America’s top leaders and its major intelligence agency.” Although none of the charges against him proved true, he is still held in isolation at Guantánamo.

Then something surprising happened. I received an email message from someone I’d heard of but never met. Joseph Margulies was the lead counsel in Rasul v. Bush, the first (and unsuccessful) attempt to get the Supreme Court to allow prisoners at Guantánamo to challenge their detention in federal courts. He is also one of Abu Zubaydah’s defense attorneys.

He directed me to an article of his, “War Crimes in a Punitive Age,” that mentioned my Abu Zubaydah essay. I’d gotten the facts of the case right, he assured me, but added, “I suspect we are not in complete agreement” on the issue of what justice for his client should look like. As he wrote in his piece,

”There is no question that Zubaydah was the victim of war crimes. The entire CIA black site program [the Agency’s Bush era secret prisons around the world] was a global conspiracy to evade and violate international and domestic law. Yet I am firmly convinced there should be no war crimes prosecutions. The call to prosecute is the Siren Song of the carceral state — the very philosophy we need to dismantle.”

In other words, one of the leading legal opponents of everything the war on terror represents is firmly opposed to the idea of prosecuting officials of the Bush administration for war crimes (though he has not the slightest doubt that they committed them). Margulies agrees that the crimes against Abu Zubaydah were all too real and “grave” indeed, and that “society must make its judgment known.” He asks, however, “Why do we believe a criminal trial is the only way for society to register its moral voice?”

He doubts that such trials are the best way to do so, fearing that by placing all the blame for the events of those years on a small number of criminal officials, the citizens of an (at least nominally) democratic country could be let off the hook for a responsibility they, too, should share. After all, it’s unlikely the war on terror could have continued year after year without the support — or at least the lack of interest or opposition — of the citizenry.

Margulies, in other words, raises important questions. When people talk about bringing someone to justice they usually imagine a trial, a conviction, and perhaps most important, punishment. But he has reminded me of my own longstanding ambivalence about the equation between punishment and justice.

Even as we call for accountability for war criminals, we shouldn’t forget that we live in the country that jails the largest proportion of its own population (except for the Seychelles islands), and that holds the largest number of prisoners in the world. Abuse and torture — including rape, sexual humiliation, beatings, and prolonged exposure to extremes of heat and cold — are routine realities of the U.S. prison system. Solitary confinement — presently being experienced by at least 80,000 people in our prisons and immigrant detention centers — should also be considered a potentially psychosis-inducing form of torture.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.