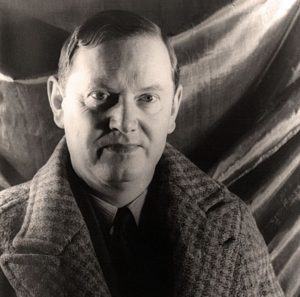

Schickel on Scorsese

In this excerpt from his new book, "Conversations With Scorsese," veteran movie reviewer and documentary filmmaker Richard Schickel describes the character, formative struggles and career challenges of the celebrated director, with whom he shared a rich dialogue spanning several decades.In this excerpt from his new book, Richard Schickel describes the character, formative struggles and career challenges of the celebrated director.

From the book “Conversations With Scorsese” by Richard Schickel. Copyright © 2011 by Richard Schickel. Reprinted with the permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House Inc.

Every time we met, we vowed to try to keep our conversations on a rough chronological track. Every time we failed to do so. He’s as breathless and excitable off camera as he is on. At some point every night we would just give up on chronology and go with whatever flow had arisen out of our exchanges. These resulted in quite amazing transcripts—full of repetitions and false starts, to be sure, but also full of fascinating autobiography and astonishing detail about the choices he has made over the course of a career that now extends well over forty years. These were never easy to edit, but they were never tiresome, either.

Like virtually every good director I’ve ever known, Marty is not entirely comfortable at explaining his motives, why he may opt for one project over another—or, for that matter, one shot or edit over another. Movie directors are as instinctive as any other kind of artist except that they have to marshal and control far more numerous and often more recalcitrant collaborators than someone working alone—a writer or painter, say. There is, as well, something hypnotic and addictive in the filmmaking process, something that drives its practitioners to immerse themselves in the work to the exclusion of all else. And it’s quite a long process. Preproduction, production, and postproduction cannot take less than six months. Sometimes, as in the case of a difficult project like The Last Temptation of Christ or Gangs of New York, it can take years, decades. You have no choice but to embrace this addiction—there is no twelve-step program that can cure you—else your picture will fail and eventually your career will fail as well.

You get the sense, when you’re around someone like Marty, that directors are not fully alive unless they give themselves over entirely to the proffered obsession. It may even work the other way. I sometimes think the reason directors occasionally embark on movies that are not up to their highest standards is that the need to obliterate themselves in a project also obliterates commonsense caution. Putting that point less melodramatically, it may, in Marty’s case, account for the fact that he meticulously draws out on paper every shot in his movies before going on set to make them. It’s not quite actually shooting the thing, but it is as close as he can come to that limbolike state that occurs while he is impatiently awaiting his start date.

This is also a reversionary state. It is exactly what he did when he was a kid, not even consciously knowing that he wanted to become a director: drawing his little movies on sketch pads and showing them perhaps to a single friend. I suppose, indeed, that the most important thing I learned about Marty—or at least had powerfully reinforced—during the course of these conversations was the power that his past exerts on his work. I’m not just talking about his drawings. Or about the films like Mean Streets or Who’s That Knocking at My Door, which so clearly contain autobiographical elements. I’m talking, for example, about the way violence presents itself in his films. It appears so suddenly. There is rarely much buildup to it, no hint of gathering menace. Some guys will be kidding around in a bar or on a street corner and suddenly, bam, someone is hurt. Or dead. That’s how Marty observed violence when he was a kid. That’s the way he presents it as a grown-up. His deadly confrontations are only rarely blood-drenched. They are more often over before we sense them starting. He wants us to be as shocked—and as wary— as he once was. It is the inbred signature of his sensibility.

I’m also talking about what I’m afraid I have to call his spirituality. In the pages that follow the reader will find much about Marty’s struggles with questions of faith and belief when he was growing up. One thing people with only the most superficial knowledge of Marty’s personal history know is that he “almost” became a priest. That is not true; to his chagrin, he found that he could take only the briefest steps along that path. For some time he counted it as a major life failure (though he seems no longer to feel that). It has also led some people to see his passion for film as a substitute for formal religious belief, which is far too easy an explanation for this career. But just as the kind of violence he observed as a kid is present in his movies, so are his youthful yearnings for belief. It’s obvious, of course, in pictures like Kundun. But there are hints of those aspirations, a longing for some kind of transcendence, or, at the least, relief from reality’s harsher limits, in so many of his secular films. It’s obvious in such early films as Mean Streets, less so in films like The King of Comedy, Goodfellas, and The Age of Innocence. But in one form or another, in small ways and large, his concern with matters of belief is nearly always present in his work.

So is his concern with betrayal. The picture for which he won his too-long-delayed Academy Award, The Departed, is a kind of festival of double-dealing, with Matt Damon’s and Leo DiCaprio’s characters acting as spies—one in the cops’ camp, one in the criminals’—and a rich variety of subsidiary characters joining in the deadly game the film portrays. Something similar occurs in Goodfellas. In a film as relatively minor, yet darkly farcical, as After Hours, a square young uptown man ventures into downtown New York persuaded that he’s going to get laid by an attractive pickup he’s met in a coffee shop; he nearly gets killed by her and her self-absorbed and heedless friends. And when you come to something like Raging Bull, Jake LaMotta’s suspicion that his wife may be betraying him—she is not—drives much of the story, and a large portion of its violence. I don’t believe that Marty is himself particularly paranoid—though he does have mirrors up in the “Video Village” from which he operates on his sets and in his editing room, so that no one can catch him unawares, from behind his back. And he does speak of being taught, as a kid, not to react to the suspicious behavior that went on around him. Eyes front (and blank), lips sealed—that’s how he passed many of his years in Little Italy. Where he grew up, almost all the deadly behavior he observed stemmed from someone betraying or attempting to betray someone else, whether the business at hand was criminal, familial, or something as simple as an attraction to a pretty girl (see his first feature, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, which seems to me underappreciated, especially by Marty himself).

Finally, there is this irony to contemplate: Marty is obliged to make his living in an “industry” controlled by people who have always wanted to impose rationality on their enterprise, have always tried to tame its wild children. Or ostracize them. Or break them. The idea that making movies at the highest level can ever be a fully reasonable activity has always struck me as laughable. But forget that. The point I am making is that the studio and the filmmaker have different motives and that the relationship between them is bound to be mistrustful, therefore rife with the possibility of—yes—betrayals. There’s this cliché about Hollywood—“It’s high school with money.” But you have to wonder: What if it’s actually Little Italy without gunplay?

If that’s the case, it becomes possible to imagine that what Marty observed and learned in his formative years was the best possible preparation for the career he later took up. Which, in turn, is a way of saying that in a fairly deep sense he is an autobiographer—not so much an anecdotal one, but one of his inner life, his yearnings, his feelings, his fears in his formative years. Nor is that impulse limited to his portrayals of criminal life. To give just one example that came up in the course of our talks, he observed that the codes of conduct enforced by New York’s upper classes on Newland Archer and Ellen Olenska in The Age of Innocence are as harsh and unforgiving as any administered by the modern-day Mafia.

His is not the only way to make good movies. There is much to be said for the show of calmness in a line of work where the pretense that reason rules may be the nuttiest idea of all. But I’m here to tell you, there’s also much to be said for sitting up half the night listening to the spiraling enthusiasms—and the occasionally drowned dreams—of a man who cannot help but make the kind of commitment Marty has made to every aspect of filmmaking.

In a sense, Marty’s passion is his saving grace. It is so intense that when you’re in its presence you have only two choices: embrace it or flee it. The former course is, for me, at least, infinitely more rewarding. You can learn so much from him—not just about old movies you really ought to see, or re-examine more thoughtfully, and not just about how to achieve all kinds of potent movie effects (how to stage a scene or fire up an actor or find a solution to a technical problem). Somehow, as I’ve grown closer to Marty in recent years, that famous formulation of Henry James’s keeps tugging at my mind: “We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

It would be nice someday to apply that grandiose sentiment to a mere movie-maker without feeling a twinge of embarrassment. But there it is—it fits this case. And the case continually redeems himself by knowing what an absurd figure he can sometimes cut. He is also, in my experience, a courtly man—impeccably dressed in his European suits, a generous host, a man widely read in Greek and Roman history (some of those sketch movies he made as a child were epics about the classic age), and in the writings of men and women who share his need to lift himself out of the quotidian, to find something more than the brute reality of everyday life.

“I’m not an animal,” Jake LaMotta murmurs to himself when he finally touches bottom in a jail cell. And he is not the only such figure in Marty’s films. They may be full of “animals,” but for the most part these are balanced by figures who, following dim and enigmatic instinct, aspire to transcend their ignorance and their circumstances, to find some touch of grace in their grim and circumscribed lives. But there never has been and there never will be “a triumph of the human spirit” in a Scorsese film. He’s too intelligent for that. And too sternly moralistic. What I respond to most in his films is not just that they are unsettling, but that they generally remain unsettled. His stories reach their firm narrative conclusions, but they remain open-ended. You are always left wondering what might happen next to his survivors. And thinking that probably their fates will not be entirely contented ones.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.