Reports of Publishing’s Death Are Exaggerated

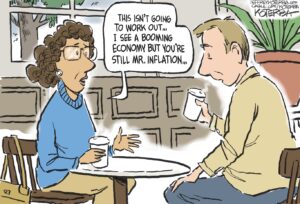

Some people think the book business in on its last legs. But others think it isn't a business at all.

“Oh, good, it’s time for the NYTimes to ask if the book business is dead. Again,” tweeted It Girl literary agent Julie Barer recently. Barer’s tweet linked to a New York Times Magazine article about a proposed merger between Random House and Penguin that began this way: “When you see a merger between two giants in a declining industry, it can look like the financial version of a couple having a baby to save a marriage.”

Everyone who works in publishing read the article “How Dead Is the Book Business?” by NPR Planet Money co-founder Adam Davidson. Nobody liked it much, mainly because Davidson dared to compare book publishing to envelope manufacturing. His article was less notable for its brilliant insights into the industry — there weren’t many — than for its unstated assumption: Publishing, once a wood-paneled gentlemen’s club where martinis and lofty literary ideals trumped tawdry financial concerns, is just another business.

Many people think publishing isn’t a business at all. Book publishing is a clubby, insular world where everyone knows one another and started as an eager 22-year-old fresh out of Vassar. Publishing people have not moonlighted as gas station attendants. (There are very few gas stations in Manhattan.) They have not worked in homeless shelters or insane asylums. They have never been anthropologists in Borneo or studied raptors in Bolivia. They have, of course, read about these things, which they believe qualifies them to judge whether books written by people who actually have done them are worthy of publication. They don’t believe that outsiders understand what they do, least of all a crass business reporter.

The culture of book publishing is one reason for its current woes. In the long run, that eccentric nature might be the industry’s salvation. In the short term, though, it’s hard to tell whether vulture capitalism will mend publishing’s problems or make them worse. Barer was right: The book business isn’t dead. But it is changing, and the book companies that emerge will bear as little resemblance to their predecessors as the gangster who has plastic surgery and comes out looking like someone else — because he is, indeed, played by another actor. Whether you think that’s a good thing may come down to whether you own stock in the company.

The one certainty is that there’s no turning back. John Tayman, the founder of Byliner, an online publisher that shares profits with writers, calls it a transition from analog to digital. But it’s more than that. Shopped at Target recently? The landscape of publishing looks like America itself: a few monopolistic corporations duking it out for 80 percent of the profits, small to medium-sized presses where people do it for love but wouldn’t mind a smash hit, and tech innovators determined to prove that doing good while doing well is not an oxymoron (but if it goes belly up, they’ll still have the house in Noe Valley, the BMW and the book contract). Workers, you say? Oh, them. Workers — in this case, writers and, to some extent, editors — face narrowing opportunities, low wages and zero job security.

Industry boosters stave off criticism by pointing out that more books are getting published now than ever before, and trendy literary fiction has a certain amount of zing, thanks to proliferating MFA programs. But there’s no question that corporate consolidation narrows the channel for writers. In some cases, literary agents won’t approach more than one editor at a publishing house, even if there are a number of imprints under the same roof. (An imprint is a unit within a publishing company that has its own staff and identity. According to literary agent Andy Ross, Random House had 56 and Penguin 39 at last count.)

At a recent conference of literary writers in New York, both Barer and veteran literary agent Gail Hochman acknowledged that many good books simply don’t get published. What’s maddening is that these decisions often don’t make sense either artistically or commercially. Even a well-regarded author who violates the industry’s shibboleths may run into trouble, and those shibboleths seem as numerous, and as irrational, as the taboos on an isolated Micronesian island.

Take the case of Chris Beha, one of the writers who appeared at the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses conference held in New York in early November. Beha is an associate editor at Harper’s Magazine, and he is not anyone’s idea of a mediocre talent. An unassuming genius in the David Foster Wallace mode, Beha studied with Joyce Carol Oates at Princeton. Grove published his first book, a memoir titled “The Whole Five Feet: What the Great Books Taught Me About Life, Death, and Pretty Much Everything Else,” to stellar reviews.

But Beha is really a novelist, not a nonfiction writer. His next book was a novel about a struggling young writer living in Greenwich Village and a girl he loved in college who had abandoned her literary calling for Catholicism. “What Happened to Sophie Wilder” examines the difference between living life and writing about it.

Unfortunately for Beha, the novel violated the cargo cult belief among publishers that nobody wants to read about writers. (If you’re a literary type and tempted to mention that Philip Roth didn’t get the memo on that one, you wouldn’t be the first.) When “Sophie Wilder” failed to win a contract from one of the Big Six, Rob Spillman, editor of Tin House Books, jumped at the chance to publish it. The story has a happy ending: Amazon featured the book as a digital download deal of the day and it wound up No. 1 in literary fiction, selling more than a thousand copies in 24 hours. D.G. Myers, a critic for Commentary magazine, called it, flat out, the best book of the year.

Beha’s experience illustrates the real problem with the Bain Capital-inspired changes now taking place in the industry. There’s no guarantee that the corporate strategy of “bigger is better” will solve the book business’ structural problems, or even result in better sales. Economies of scale may help publishers go digital, but it’s interesting to note that the overall failure rate for mergers and acquisitions is roughly the same as the percentage of books that don’t earn out their advances: 70 percent, according to the Harvard Business Review, putting MBAs in roughly the same category as feckless English majors-turned-editors in terms of predicting success.What’s a publishing CEO to do? The industry’s problems are easy to understand. The contraption was jury-rigged from the beginning, and the business model is the equivalent of the QWERTY keyboard. Take, for example, the fact that bookstores can order as many books as they want and if they don’t sell, the stores can send them back to the company and get fully reimbursed. This arrangement is a relic of the Great Depression (the one in the 1930s, not the one we’re in now) and is often cited as the most obvious example of the industry’s longstanding structural problems. But there are other oddities. Book contracts are, in many cases, a shell game. The financial arrangement of “advance against royalties” allows publishers to subsidize writers, compensating for royalties that, in standard publishing contracts, can be as low as 8 percent for the first 20,000 copies of a book.

“Sometimes publishers will write a contract for a major author that says we’ll give you 22 percent, knowing it will never earn out,” publishing consultant Mike Shatzkin said. “The sharp agent negotiates a royalty that’s considerably higher than that. These aren’t always mistakes. It’s not a royalty on paper, but an advance that’s essentially a royalty.”

With accounting metafictions and antiquated baggage, how do publishers make money? One might well ask. The glaring inefficiencies of the business are offset by blockbuster sales. In fact, publishers operate very much like writers, who tend to use the last check from their advance to pay off a whopping Visa bill. So far, it’s worked. The Random-Penguin merger was driven not by ledger sheet losses but by the market creep of Apple and Amazon, both of which are far larger than any publishing company. But an overreliance on bailouts by next year’s “Fifty Shades of Grey” creates an atmosphere of fear and frustration that one observer called “toxic.”

It’s hard not to sympathize with corporate executives who are appalled by publishing’s Rube Goldberg business model. But for the last 20 years a succession of corporate players ranging from oil companies to movie studios have applied MBA logic to a business that, at its core, relies on a different kind of thinking entirely. The lifeblood of the book business consists of long-term relationships and the cultivation of talent. But the world of Big Box publishing is driven by stock prices, and if a writer’s first book doesn’t sell, she may not get another published.

“The most important thing that big publishers traditionally offered was transference of risk,” Shatzkin said. “The Big Six, probably 20 to 25,000 times a year, take the risk from an author onto themselves. That means the risk involved in getting the book ready for publication, making it, publishing it, distributing it. What’s happening now is the publisher is saying in this current marketplace I can’t accept this risk for myself.”

Publishers may improve their bottom line by ratcheting down advances, getting rid of the dreaded mid-list (books that sell less than 25,000 copies), and externalizing their costs, but Shatzkin believes this kind of tough love may weaken them over the long run. Publishing isn’t dead — really! — but in a few years, the Big Six (or Four, or the Massive Two, as one pundit predicted) may resemble a wounded mammoth fighting off a veritable Noah’s Ark of more recently evolved predators. These include not only Apple and Amazon, but feisty midsize presses and innovative startups like Byliner, which offer a direct connection between writers and their readers.

For now, most writers need a quicker fix: the credibility and decent-sized advances that only big houses offer. By default, the common wisdom these days is: “You just need to find the right agent,” as if the right agent will miraculously transform a shy introvert into a smooth-talking Master of the Elevator Pitch, plus get said introvert a movie deal. The right agent will find the right editor, the one who will risk losing her job in the next wave of corporate layoffs simply because she loves your book so much.

That’s all true, unless the marketing people use their veto power. If publishing a book is starting to sound like a sex-ed movie from eighth grade starring the plucky single sperm who outraced the other 100 million sperm (and never mind all the things that might go wrong after conception!), that’s not far from the mark.

One of the reasons literary agents have become more powerful than editors is their relative job security, since many are sole proprietors. But agents are realists, not revolutionaries. Book publishing historians consider them part of the problem. The literary agent was invented in the 1920s, an innovation that increased competition while failing to address the industry’s structural flaws. That dynamic intensified in the 1980s, when Andrew Wylie (nicknamed The Jackal) leveraged near-miraculous advances for his clients. Like the housing bubble, big advances were a fleeting high (most books did not earn out their advances) followed by a lengthy and decidedly unpleasant hangover.

These days, literary agents, though invaluable to writers, shore up the publisher’s practice of externalizing risk. They have no choice. As the bar for selling a manuscript has risen, agents do the work of editors, spending as much as a year working with a writer on revising a manuscript. Many are editors who were felled in one of the cost-cutting putsches resulting from corporate consolidation. But they don’t make any money unless the book sells, so it’s no surprise that they’ve become increasingly selective about taking on clients, which makes life even harder for writers. Some writers hire a freelance editor to get their manuscript into shape before approaching an agent. Others attend an MFA program, or perhaps two, since it can take five to seven years to write a first novel.

You could call it trickle down book publishing. Not only are agents taking on the risk of editing a book, but after the book is sold, writers are paying for their own marketing and publicity, as well as niggling things like rights to photographs and indexing. It’s like air travel in the age of print-your-own-boarding pass, and paying $25 per suitcase — standard-issue corporate behavior, circa 2012. But at least one writer who’s capable of adding up a balance sheet isn’t impressed with the results.Porter Bibb is one of those ageless 1960s wunderkinds who love both art and commerce, and because he sees publishing from both sides, he understands the move to digital publishing better than most. (Graphic designer Roger Black and Sports Illustrated editor Terry McDonell are among the others in this unusual group.) An investment banker who is often quoted about media and technology, Bibb attended Louisville Male High School with Hunter S. Thompson. He was Rolling Stone’s first publisher, covered Washington, D.C., for Newsweek and is the author of five books.

Bibb may not wear mismatched Converses or hang out in Park Slope, but when he talks about his experience as an author, he sounds like every other disgruntled hack.

“The last book I did was a biography of Ted Turner for Random House five years ago,” Bibb said. “I brought it in, and they said, ‘Are you gonna edit it?’ I had to go out and hire a professional. Then they said, ‘It’s 750 pages. We want to cut it down to 500.’ I said, ‘Are you selling books by the pound?’ “

In the end, Bibb not only hired his own editor; he also sprang for his own public relations agency and marketing consultant. He sold excerpts to Newsweek and the New York Post. When he asked about foreign sales, the publisher told him the book didn’t have the potential to sell in other countries. Bibb, furious, bought the foreign rights back and sold them himself. The book was published in 14 countries, including Taiwan and mainland China.

“The agent basically disappeared into the woodwork, because she didn’t want to suffer the consequences of my brashness,” he said. “I just couldn’t let the book die. I said, ‘You didn’t edit it, you didn’t promote it, what do you do?’ “

The answer, five years ago, might have been distribution. Now, not so much, with Amazon dominating distribution, Apple hard on its heels and Google playing catch up. There are, of course, other advantages to being published by a major house. Traditionally, only books from big publishers were widely reviewed. But that’s changing, too. Book critics are few and far between, marketing and promotion are evolving into new forms, and books published by independent presses are regularly reviewed in the prominent venues that still exist, including The New York Times Book Review.

“The reality is that the book business is going through the same trauma and disillusion that the music industry has already gone through,” Bibb said. “Twelve years ago, there were 30 or 40 independent music companies. Only three or four of them were really big, but they were all making money. Then the Internet came along and capitalized on the fact that people would rather buy one song they like without paying for the 18 they don’t care about. There are now three record companies — soon to be two. The book business has seen this coming and like everyone else in the media industry they have put their heads in the sand, and said ‘This isn’t going to happen to us.’ “

The problem for writers is that the new models haven’t completely emerged from the primeval swamp of American entrepreneurship. Thanks to an infusion of nearly $1 million in seed funding, Byliner is evolving more rapidly than most. Tayman, a former editor of Outside magazine who co-founded the company with another Outside editor, Mark Bryant, and Ted Barnett, a Harvard Business School MBA with Silicon Valley roots, said the idea for Byliner came not from spreadsheets, but from his gut.

“It grew out of some frustrations I had been feeling as a magazine editor and writer and as a book writer,” Tayman said. “I had been in magazines for quite some time. I took a break and did a book for Scribner in 2007 [‘The Colony,’ about leprosy victims exiled on the Hawaiian island of Molokai]. Happily it did really well, so the publisher and agent were both saying, ‘Let’s get you going on another one immediately.’ “

But after spending four years on the book, Tayman wasn’t ready to take on another big project.

“I had a backlog of story ideas I wanted to write,” Tayman said. “As I looked at them, I realized they didn’t fit into the magazine model. At the same time, they weren’t stories that would benefit from a couple years of my life and 100,000 words. They would be perfect at 10,000 to 20,000 words, and I was looking for something that could be on and off my desk in a month or two. The idea of being able to start and enjoy a story in two hours or less was appealing to me as a reader.”

Tayman had stumbled onto a new category of e-books called “singles” designed to be read in a single sitting. In early 2007, before the first Kindle was introduced, Tayman started sending out emails, brainstorming the idea of Byliner with friends and colleagues.

“Because it was before tablets were introduced, I knew there was going to have to be a different method of discovery for these stories, but that method wasn’t obvious,” he said. “I thought it should be direct, from the writer to the reader. Writers never own their relationship with their readers. I had been a magazine writer for 15 years but there was no way for me to market my book to the people who had been reading my work.”

Bankrolled by angel investors in Silicon Valley (yes, it has a business model), Byliner publishes original work under 30,000 words and is building “portfolio” pages where established writers can post their backlist of short stories or magazine articles. Byliner’s first release was Jon Krakauer’s “Three Cups of Deceit,” an exposé of the misuse of funds by mountain climber and “Three Cups of Tea” author Greg Mortenson. “Three Cups of Deceit” posted in April 2011, and proved to be a boffo opener: 70,000 readers downloaded a copy in the first 72 hours, before the text migrated to the Amazon Kindle store and became the No. 1 seller there.

“Three Cups of Deceit” was also great PR for Byliner, because it embodied the ethic of moneymaking with a gloss of social responsibility that is part of Silicon Valley culture. Not only did the story appear as a “60 Minutes” segment, but Krakauer donated his profits from the work, which later appeared as a book, to an organization fighting human trafficking of young girls in the Himalayas.Byliner didn’t charge for the download of Krakauer’s piece, but soon established a model through which writers and Byliner split proceeds from the usual $2.99 download price in half, minus 30 percent for distribution by online stores, including Amazon and Apple. Although the division made sense on paper, it is also symbolic of what publishers such as Tayman and Spillman call a “partnership” between themselves and writers, a model they say is very different from old-school publishing.

Byliner, with its philosophy of sharing both risk and profit, has attracted original writing from a number of well-known writers; in addition to Krakauer, Margaret Atwood, William Vollmann and Alexandra Fuller have also contributed. All are still writing books published by major houses. But a couple of years ago, profits from the stories they post on Byliner would have gone to traditional publishers of either books or magazines. Last week, Byliner landed a first round of serious financing from a lineup that includes venture capitalist firms, along with book distributor Ingram and Random House.

Byliner and similar online publishing venues The Atavist and Longform tend to publish established authors. Unlike Salon, the feisty Internet startup that broke major stories in the 1990s, these sites aren’t necessarily pioneering innovative content. Emerging writers are gravitating to websites that pay little or nothing at all, like The Rumpus, which helped make Portland, Ore., author Cheryl Strayed (“Wild”) a best-selling author. And some writers are choosing to keep control of their own work, betting that it won’t be long until technology advances sufficiently to make distribution as accessible as e-book publishing is today.

Midsize dead tree publishers such as Tin House and San Francisco-based McSweeney’s are also expected to benefit from changes in the industry. These firms are steeped in publishing’s greatest strength: quirky creativity. Tin House editor Spillman says that Barney Rosset, once called “the most dangerous man in publishing,” is his literary hero. Rosset, the founder of Grove Press and Evergreen Review, published D.H. Lawrence, Samuel Beckett, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, Kenzaburo Oe, Harold Pinter, Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco and Tom Stoppard. Five are Nobel Prize winners and several are writers whose work was banned on several continents. (One might note that having your books banned was not, in those days, a good sales ploy.) In the end, Rosset’s writers sold millions of books. But if there was a strategy on his part, it was decidedly long term.

“Barney Rosset invested in people like Samuel Beckett,” Spillman said. “He wasn’t worried about having one Stephen King. For a corporate publisher, if they give someone a $40,000 advance and the book only sells 5,000 copies, it’s a disaster. Whereas for us, if we sell 5,000 we’re happy. For literary publishing, the pressure to have every single book become a breakout book is kind of unrealistic. It doesn’t do for a long-term relationship.”

But is it still possible to operate like Rosset at a time when the cost of everything seems astronomical?

“Absolutely,” Spillman said. “The word nimble comes to mind. Places like Graywolf, Soho, McSweeney’s, they all have very low overhead versus a company like Bertelsmann. When you get that big, it’s very hard just to cover your overhead.”

The good news is not that a change is gonna come, but that it may happen sooner rather than later. Chris Anderson’s 2006 book, “The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More,” argues that our culture and economy are moving away from a relatively small number of “hits” and toward engaging a large number of small markets. In the past, small retail outlets like bookstores depended on big hits because they had limited shelf space. But when infinite shelf space (à la Amazon) is taken into account, the true shape of demand is revealed, Anderson writes, and it’s less hit-centric than we thought. Selling less of more results in just as many sales as engaging a small number of large markets. (To torture a metaphor, Monty Python fans could call it the “Every Sperm Is Sacred” business theory.) Anderson uses the music analogy: Cheap Internet distribution has allowed services such as Rhapsody and iTunes to cater to virtually any market cheaply, no matter its size.

But as new business models emerge, they bring new struggles for writers and publishers, as revealed in the fight between Amazon and Apple. With the behemoth Amazon discounting best-sellers to gain market share, five major publishing companies cast their lot with Apple. Apple would distribute books at a price set by the publishers, with 70 percent of the cover price going to the publishers and 30 percent to Apple.

In April, the U.S. Department of Justice sued both Apple and the publishers not for antitrust violations, but for allegedly colluding to raise prices. A few months later, three of the five book companies agreed to a settlement that allows Amazon to continue using best-selling e-books as loss leaders — a practice Authors Guild President Scott Turow calls predatory pricing — as long as the publisher’s entire e-book list does not lose money over a 12-month period.

Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., protested the settlement in The Wall Street Journal, claiming that it could “wipe out the publishing industry as we know it and make it much harder for young authors to get published.”

Reading the Authors Guild’s letter of protest regarding the settlement to the chief of the DOJ’s antitrust arm is a fascinating precis of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’ brilliant if ruthless business strategy. The Authors Guild characterizes it as vertical integration: Amazon is publishing print and e-books, as well as distributing them but so far, Apple is confining itself to distribution.

One of the Guild’s most compelling arguments against the DOJ’s settlement is market share. Amazon controlled 90 percent of the e-book market before Apple entered the fray; now that slice is down to 65 percent.

Why should writers care? If Amazon dominates virtually every aspect of book publishing, the company will be able to reduce authors’ royalties dramatically. Both established authors and self-published writers would be forced into the Amazon corral.The book industry has been consolidating for a long time, but after the settlement the pace increased as publishers reached for the next line of defense. Random House and Penguin announced their merger Oct. 29. Within weeks, industry pundits reported that merger talks were under way between Simon & Schuster and HarperCollins, with Harper’s parent company, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., slated to be the controlling owner. Soon rumors surfaced of even more mergers.

Someone once called alcoholism “the writer’s black lung disease.” As the pathway for publication narrows, envy has replaced whiskey as the writer’s cocktail du jour. Nobody did a better job of describing that mind-bending jealousy than British novelist Martin Amis in “The Information,” recounting the reaction of once-promising writer Richard Tull as he glares at the crowded bookshelves of his more famous friend. “What he minded were Gwyn’s books: Gwyn’s books, which multiplied or ramified so crazily now. The lambent horror of Gwyn in Spanish (sashed with quotes and reprint updates) or an American book-club or supermarket paperback or something in Hebrew or Mandarin or cuneiform or pictogram. …”

Writers would be better off turning their considerable energy toward sussing out the business of publishing. As recently as 10 years ago, good writers could support themselves from their writing. Now many of them can’t. Until a new ecology of publishing is invented that offers decent wages and opportunity, articles and short stories will not be written, and books that you might have loved will not get published.

What’s a writer to do? Agent Barer’s oft-quoted advice is: “Don’t quit your day job.” For many writers, it might be: “Don’t quit your three jobs: the one you work to make money and get health insurance, the one you work to make contacts and leverage your own writing, and, yeah, the one you do for love: writing.” In other words, raid Lance Armstrong’s medicine cabinet.

More and more writers are hedging their bets, writing for Big Box publishers but laying the groundwork for a career with smart, feisty new media of one sort or another. They’re not the only ones trying to figure out their next move. The Planet Money guy was right about one thing: when it comes to money, publishing is just another passenger on America’s bumpy ride into 21st century globalization. The good news is that so many of us are returning to the hardscrabble inventiveness that has defined the country’s character since the beginning, according to journalist Jack Hitt. Hitt’s recent book, “Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character,” casts the tinkerer in the garage who turns out to be Steve Jobs as a foundational American myth. Amateurism emerges when “the culture around you won’t let you out of where you are or into where you want to go,” writes Hitt. In his estimation: “The cyclical turn to the garage is happening now as Americans sense that some great turn in history has come.”

In “The Long Tail,” Anderson notes that the average book in the U.S. sells 500 copies. For writers and editors hoping to improve those odds, the best strategy may not be Fordism — the mass production embraced by big publishers — but a return to traditional American values; in the words of Bill Henderson of Pushcart Press, “happy, cranky individualism.”

(Disclosure: It would be difficult for a writer to produce a story on publishing without running up against a number of relationships. I am a member of the Authors Guild. I have written for The Rumpus. Before writing this article, I contracted with Byliner to feature the backlist of my articles.)

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.