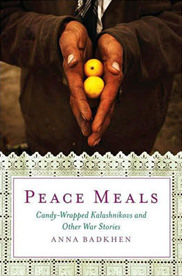

‘Peace Meals’: Breaking Bread With War’s Forgotten Families

"Peace Meals" is a tribute to all my host families who live, and perish, on the edges of the world It is my invitation to connect with the ordinary people trapped in mass violence of the last decade in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries.

Author’s note

:

The man who kept me safe and fed in Afghanistan last spring is dead. He died of blood cancer, at home: in pain, but in peace, surrounded by his wife of almost 40 years, and his 13 children.

The week he died, the United Nations released civilian casualty figures. In the first six months of this year, the war killed 1,271 Afghan civilians. The total confirmed death toll from the war among Afghan civilians is 7,324 since 2007.

We don’t know how many Afghan men, women and children were killed between 2001 and 2007, the year the U.N. began to systematically track civilian fatalities there. One estimate suggests 14,000 civilians were killed in the last nine years. Another puts the figure at 34,000.

My host’s death will never be listed as one of war’s casualties: Old men die of cancer everywhere. But as far as I am concerned, the war killed him.

In his corner of the Central Asian war zone, there is no chemotherapy. There are no bone marrow transplants. There are few oncologists, and fewer advanced diagnostics to detect the disease early: Government clinics in Afghanistan are free, but most of the equipment dates back to the Soviet occupation. In a country where less than a third of adults can read and policemen adorn their stations with ram’s horns to block jinxes, few people recognize the symptoms of such disease in time. In my host’s final weeks, his family relied on the prayers of a local mullah and the sorcery of a witch doctor whose TV advertisement—“Treats with Plants and Herbs!”—had promised an instant cure.

How many civilians have perished because war, which has been ravaging Afghanistan almost incessantly for millenniums, has decimated the land’s infrastructure, stunted its health care and sentenced millions to deaths that could have been prevented, or at least significantly postponed? One in eight Afghan women dies during childbirth. One in four children dies before the age of 5, mostly of waterborne diseases. Only a third of Afghans have access to clean drinking water; fewer than one in 10 have access to sanitation facilities. Life expectancy, both for men and women, is 44 years.

No one ever tallies these deaths.

Beyond the mountains, writes the Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat, “there are timeless waters, endless seas, and lots of people in this world whose names don’t matter to anyone but themselves.” We often dismiss the peopled landscapes of Afghanistan—and Iraq and Kashmir, Chechnya and Somalia—as merely a sere battleground of the global war against Islamist terrorism. We erect an emotional wall between ourselves and the millions of nameless, two-dimensional figures that move across our television screens, foreign and strange, almost cartoon-like, unsung. One goes up. One goes down. We switch to a different channel.

My host’s name was Nur. He was like many others who have died in Afghanistan. He went to the mosque every Friday, although he wasn’t very religious. He sacrificed a goat on holidays and divided the meat among neighbors poorer than him. I never saw him read—although, unlike most Afghan adults, he knew how. Whenever there was electricity in the house—not very often, because in Afghanistan electricity, like all other commodities, is sporadic—he watched Iranian soap operas.

For a month, the old man was a father to me: because his youngest granddaughter called me Auntie Anna; because he waited for me by the gate each time I made forays into regions under Taliban control; and because in extremity, an offer of shelter is an invitation to join the family.

“Peace Meals” is a tribute to all my host families who live, and perish, on the edges of the world. It is my invitation to connect with the ordinary people trapped in mass violence of the last decade in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East and in East Africa; to break bread with them; and to peer past the looking glass of warfare led or backed by the United States into the lives of the people who, despite the violence and privation that kill their loved ones and decimate their towns, somehow, persevere.

Even if they are not mentioned in the daily news feed, they have names.

* * *Excerpted from “Peace Meals: Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs and Other War Stories” by Anna Badkhen. Copyright © 2010 by Anna Badkhen. Excerpted with permission by Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.Candy-Wrapped Kalashnikovs

High on Valium and potent Afghan hashish, Najibullah balanced his Kalashnikov rifle on his left shoulder and reached for the jelebi: a pyramid of honey-colored, deep-fried rings of hot, syrupy dough stacked on a street vendor’s dusty aluminum folding table by the side of a potholed dirt road. He hooked one jelebi: with his long index finger, raised it above his head, lifted his bearded face, and, crooning a Bollywood jingle in a tentative falsetto, began to nibble at the sugary doughnut like some tropical bird, swaying slightly to the rhythm of a song that he alone could follow.

Our clunky Toyota minivan was parked near a bustling outdoor bazaar in the wooded foothills of the Spin Ghar range in eastern Afghanistan, where Osama bin Laden was believed to have been hiding in a honeycomb of caves, tunnels, and bunkers outside the town of Tora Bora. The mountain complex had been a favorite hiding place for generations of Afghan fighters—warriors who had fought against the British, then the Soviets, then against each other, and now against U.S.-led forces. It had been so elaborately upgraded over the years that by 2001 it was said to have its own ventilation system and a power supply provided by hydroelectric generators.

Whatever had been in these massive caves on the border with Pakistan was being destroyed at that very moment. It was December 2001, and the Battle of Tora Bora was under way—a massive, joint aerial and ground attack by American forces trying to smoke out the terrorist mastermind and a thousand al Qaeda and Taliban fighters believed to be hiding with him. I had come to Spin Ghar to write about this battle.

Guided by U.S. special forces commandos and backed by scruffy Afghan guerrillas, the Americans were pummeling the caves with a dazzling array of ordnance delivered by B-52 bombers, F-14 and F/A-18 Hornet fighter jets, and AC-130 gunships: “daisy-cutters” (fifteen-thousand-pound bombs that, when they explode, create a blast wave that kills everyone within roughly three acres, leaving in their wake enormous charred craters and very little else); bombs equipped with sensors known as JDAMs (for “joint direct attack munition”) to guide them to their targets; cluster bombs packed with dozens of bomblets that could wreck roadways and runways and cripple infantry (and, as I had learned in Mengchuqur, civilians unfortunate enough to happen upon them later); and TV-guided air-to-surface missiles that weighed three thousand pounds. I could feel the impact through the soles of my feet miles away whenever the heavier payloads struck the caves. The echo of occasional gunfire ricocheted off the steep slopes, making the firefights seem both dangerously close and elusive. A week earlier, Najibullah had been holed up in an abandoned mountain barn near one of those caves, fighting al Qaeda and Taliban gunmen. Snow had coated the mountains outside, and Najibullah had been freezing in his light summer clothes. Now he was kicking back after a lifetime of war: the Eastern Shura, a loose coalition led by tribal elders who opposed the Taliban and therefore had allied themselves with the United States, had finally prevailed in this corner of Afghanistan—although it was impossible to say that the area had been purged of the Taliban, just as it would have been wrong to say that the Eastern Shura had established complete control. The mountainous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, where many Taliban fighters had found refuge, was not really guarded by anyone on either side. Some members of the militia were still holding out around Tora Bora, taking potshots at American special forces operatives and Western journalists who crawled about sections of the mountainside. Some had blended in with the local population: in line with a long-standing Afghan tradition, which allows the victor to choose, at will, between violently punishing the defeated foe and granting him complete forgiveness (this code of war also permits the victor to double back on his choice unpredictably at any given moment), the Eastern Shura had allowed most local Taliban fighters to walk free (theoretically, they were supposed to surrender their weapons). The locals, mostly ethnic Pashtuns, had largely supported the Taliban regime, and Najibullah believed that many al Qaeda members, too, had gone into hiding and were being sheltered by villagers in hamlets like the one where we were buying sweets—a cluster of mud-brick and straw huts clinging to the glaucous mountainside. Perhaps, Najibullah mused, bin Laden was also hiding in one of these villages, disguised as a shepherd with a coarse camel wool blanket draped over his head, shoulders, and back.

“There they go! There they go!” Najibullah had yelled earlier that day, pointing excitedly out the car window at two men in dark turbans walking down a village street. “See how they try to hide their eyes? They are former Taliban fighters!”

He rolled down the window, leaned out, and, shaking his gun—the same beat-up Kalashnikov he had carried since he was twelve—shouted at a passing villager:

“Where are you hiding the Taliban, huh?”

The villager ignored him. Our driver, Yarmohammad, decided that it was best, for the sake of our safety, not to stop.

But then Najibullah spotted the jelebi vendor and ordered Yarmohammad to pull over. Najibullah had been smoking hashish all morning, and now he had the munchies. We had to respect that. After all, this man—with his addiction to tranquilizers, his unpredictable mood swings, his little juniper hash pipe, and his disconcerting tendency to lean out of our car window and fire his gun across the valley just for fun—was our bodyguard.

— — —

I made Najibullah’s acquaintance in December 2001, toward the end of my second trip to Afghanistan. The journey had begun right after the Taliban regime fell and its army surrendered Kabul and most major Afghan cities and towns, in November. David and I had once again floated into the country across the Pyandzh River from Tajikistan, on the diesel ferry. The day we arrived two gunmen had shot and killed a Swedish television cameraman, Ulf Strömberg, in Taloqan, a city in northern Afghanistan a few hours’ drive from our first stop on this trip, the hospitable compound of Mahbuhbullah the Tomb Raider. Mahbuhbullah had heard about the killing on his handheld AM radio and told us as soon as we drove up to his house.

Strömberg was the eighth journalist to be murdered in the country in four weeks. Earlier that month, two French radio correspondents and a writer for a German magazine had been ambushed and killed after a rocket-propelled grenade blast threw them off an armored vehicle driven by the men of an anti-Taliban rebel commander in northern Afghanistan.

A week before Strömberg’s killing, four Western journalists driving in a convoy on the stretch of the ancient Grand Trunk Road* between Jalalabad and Kabul—where bandits had waylaid their prey for centuries—had been forced out of their vehicles, marched off to the side of the road, and executed. [*Grand Trunk Road—one of South Asia’s oldest routes, which stretches from Bengal in India, through Peshawar in Pakistan, to Kabul.] The journalists’ drivers, who had managed to escape, relayed the assailants’ defiant words: “You thought the Taliban was dead? The Taliban is still here!”

That was true. Wherever we went during our second trip to Afghanistan, we saw members of the deposed militia wandering around in their black turbans. Maybe they still listened to their leader, Mullah Omar, on the shortwave radios every man in Afghanistan seemed to carry in the folds of his robes. Maybe they had heard the one-eyed mullah’s promise of a fifty-thousand-dollar bounty for every Western journalist they killed.

David and I huddled on Mahbuhbullah’s earthen porch, poring over the newswire reports about Strömberg’s death that we had downloaded onto our laptops. We had not known him. But it was easy to imagine that Strömberg had been just like us: an unarmed reporter trying to find a compelling way to bring the news from this faraway, tragic land to the audience back home.

Reporters who cover wars put a huge amount of faith in the idea that none of the people we write about would ever find a reason to aim their guns at us. As obdurate as this notion may seem to anyone who has not traveled to a war zone, or anyone who has fought in one—especially given that reporters do get kidnapped and killed in wars—our almost delusionally uncritical faith in the kindness of strangers is the only thing that emboldens unarmed geeks with thousands of dollars in our money belts and, usually, few combat skills to venture into places where civilians are being killed, whether by accident or intent, by the dozen daily. This is also the main reason we react with such shock when one of our number is targeted and killed in such a place.

The news reports said that at two in the morning, two masked men armed with Kalashnikov assault rifles had scaled the stucco walls of the compound where Strömberg and three of his colleagues were staying. I glanced up at the walls of Mahbuhbullah’s compound to see whether an intruder could climb them. A bunch of our host’s kids were hanging out on top; they waved at me when they caught me looking at them.

We read on. The gunmen had taken money, computers, and satellite phones. Afghanistan was a cash-only economy, and between the two of us, David and I were carrying more than fifteen thousand dollars to pay for the services of our drivers and translators, as well as lodging, food, and other contingencies. Our satellite phone, a brand-new Thrane & Thrane, state of the art at the time, gleamed on the rooftop of Mahbuhbullah’s house: we were using it to download the reports about the Taloqan killing, at the frustrating rate of fifty-six hundred bytes per minute. The gadget’s bright turquoise LAN cable dangled from the phone to our laptops on the porch below. To make sure no one tripped over it in the dark, we had adorned the cable with little flags fashioned from reflective silver duct tape. That cable was probably the single brightest thing in this town that had no electricity.

Even if we brought down the Thrane & Thrane, this was our second time staying at Mahbuhbullah’s house, and other reporters had lived here between our visits. By now everybody in Dasht-e-Qal’eh knew that Mahbuhbullah was hosting foreigners. Strömberg, too, had been staying in a compound well known for housing foreign reporters.

In response to Strömberg’s killing, several media outlets decided to pull their reporters out of northern Afghanistan. David and I were not leaving, but we felt that we needed to respond in some manner, so we made four rules. One: we would never get out of our car in crowded public places. Two: we would avoid places where Westerners often stayed. Three: we would not travel from Kabul to Jalalabad on the Grand Trunk Road, which we privately renamed, not too creatively, the Death Road. And four: we would do something neither I nor David—who had covered the war in Chechnya for seven years before coming to Afghanistan—had ever done before. We would hire armed guards.

We ended up breaking all four rules, of course. We even spent several unsettling hours in Taloqan—not just without a bodyguard, but also without a translator or a driver. But that November afternoon in Dashte-Qal’eh, when we were pondering how to report from a land where journalists were being killed simply for being there, Mahbuhbullah, ever the discerning host, detected our unease. In the evening, after a dinner of rice, flatbread, and stewed pumpkin, he paraded several of his sons in front of us. The oldest was sixteen. The boys, Mahbuhbullah explained, would take turns standing guard in front of our room at night. We didn’t need to pay them; their services were part of our hospitality package. Mahbuhbullah showed us the weapon his kids would use: a Kalashnikov assault rifle with a well-worn wooden butt stock.

Around one in the morning, when I went outside to smoke a cigarette, I saw our guard sleeping on the porch. It was Abdullah, the industrious twelve-year-old who would always serve us the meals prepared by Mahbuhbullah’s invisible wives and clean up afterward. Mahbuhbullah’s children were better dressed and better fed than most kids in this infertile swath of northern Afghanistan. But even so, the malnutrition and disease that were so rampant in the country—in 2001, one out of four Afghan children died before reaching the age of five—had taken their toll on Abdullah. The skinny boy was about as tall as an average American third-grader.

He was my favorite of all Mahbuhbullah’s kids, with a spray of freckles on his turned-up nose, huge eyes, and a face that was quick to blossom into the most beautiful, kind smile. Now his face looked relaxed in the greenish moonlight. He was crouched up with his back against the wall and the assault rifle in his hands. He looked cold. I went back inside, fetched a flowery acrylic blanket, and wrapped it around him, trying not to disturb his gun.

The next morning, as usual, Abdullah came into our room, rolled out a plastic dastarkhan on the threadbare carpet that somewhat contained the dust on the earthen floor, and arranged on it our breakfast: last night’s leftover bread; fresh, hot eggs deep-fried in canola oil; a little bowl of salt; a small saucer of honey; and a large thermos of steaming, sweet tea. Then, with much ceremony, he approached each of us with a beat-up, plastic ewer, pouring water over a large pewter bowl so that we could wash our hands before the meal. As he squatted next to me, he asked me something in Dari, flashing his heartwarming, earnest smile. I asked Engineer Fazul, the translator we had hired at the border, to interpret.

“He asks,” the translator said, “if you think he was a good guard.”

How could I thank a twelve-year-old boy for risking his life for mine? I felt compelled to give Abdullah something, but how does one even compensate for such a sacrifice? Anything I could have done or said would have been disproportionately, ridiculously trivial. I thought of our kids, of their safe lives in big, modern cities. Alex was five at the time; Fyodor was four. I thought of what they liked. I went to my duffel bag, and fished out a Snickers bar.

Abdullah was the youngest gunman to ever guard my life. So what if he was doing it in his dreams? Of all the boys and men who have served as my protectors in Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq—some earnestly, some halfheartedly—Mahbuhbullah’s son was the most sincere in his efforts, even if his dad’s Kalashnikov was nearly as tall as he was, even if guarding me meant he had to stay up way past his bedtime, and his work went unpaid apart from a chocolaty treat.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.