Citizen Noogie

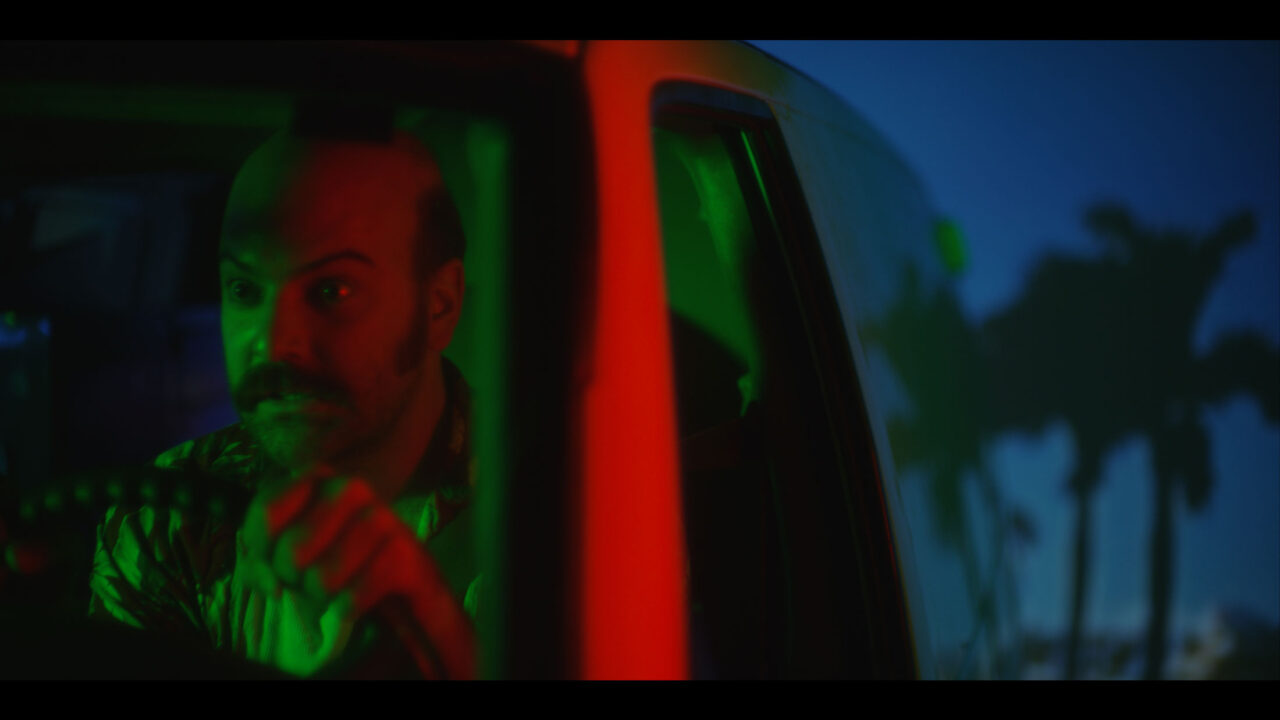

Why a novelist gave the major Hollywood studios the brush in favor of a young first-time filmmaker with no money. A scene from "Noogie's Time To Shine"

A scene from "Noogie's Time To Shine"

These days, most writers don’t write books with dreams of winning a Pulitzer or National Book Award. They write books in hopes of selling the rights to Netflix, Warner or HBO. There’s little money to be made in publishing, but there’s still loads of it in streaming and Hollywood. Stephen King and John Grisham made most of their millions selling film rights, not writing bestsellers.

As a matter of general principle, I have always been dead set against film adaptations of my books. Not because I was so precious about them, but because I didn’t trust the people asking about the rights. I knew they would fuck things up; they almost always do. It often seems as if well-paid screenwriters and directors go out of their way to miss the point.

As a writer and insufferable movie geek, I recognize that books and movies are, by their natures, radically different animals. As Alfred Hitchcock noted, it’s almost impossible to make a good film out of a great book, but fairly easy to make a great film out of a bad book. While there are rare counterexamples like “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Godfather,” the percentage of literary adaptations that are as good as, let alone better than their source novels is microscopic compared with the ocean of embarrassments and travesties. Selling out wasn’t worth the humiliation.

Of course the minute a producer showed up waving a marginally whopping check at me in 1999, all those principles went out the window. I rationalized that taking that check for my first book, “Slackjaw,” wasn’t a mortal sin because I knew it would never get made. (I also didn’t have any money at the time.) I was right about the movie never getting made, but dealing with Hollywood types for a few months was so nauseating I vowed I’d never put myself through that again. Hollywood types are not very smart and they lack anything that might be mistaken for imagination. Worst of all, they don’t seem to know very much about movies.

When I met with the would-be director, I half-jokingly suggested he cast Marjoe Gortner and Susan Tyrrell, my two favorite living character actors at the time.

“Your friends are free to audition if they like,” he told me. “But they’ll be judged the same as all the others.”

I almost threw my beer at him. My god! If he didn’t know who Susan Tyrrell was, he had no business making this movie.

Other producers continued to approach me over the next quarter-century. These days, if you wrote the owner’s manual for a self-propelled lawn mower, chances are good some studio will eventually make an offer. In my case, there was talk of a few more films, a TV series, even a Pixar movie based on one of my “children’s books,” but only after they excised all the cursing, violence and a bummer of an ending. I turned them all down without much thought. I sure could’ve used the money, but these people made me wince.

I had always preferred low-budget B-films over big budget all-star blockbusters. I’ve never seen “Titanic,” but have seen Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1945 no-budget noir film “Detour” two-dozen times. Shoestring productions tend to be more interesting and fun. They also require more ingenuity, because if you can’t afford to get something you wanted up on the screen, you have to figure a way to do it for no money. The people who make them aren’t looking to win awards or make lots of money. They made them because some twisted and misguided creative spark drove them into it. It occurred to me that most of my novels began life as B-movies in my head. That’s when I decided that if anyone wanted to adapt one of my books, it would have to be a young indie filmmaker with no money looking to make his or her first feature. They’d have more energy, more imagination and creativity. They’d throw every trick they knew into it.

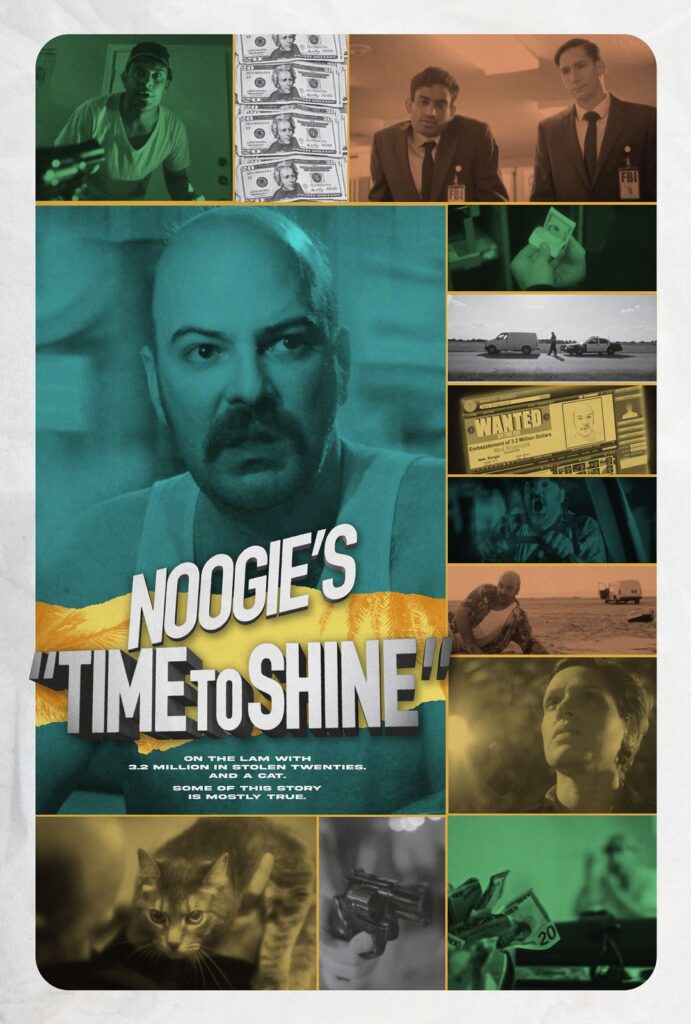

So, I had told producers from Sony, Pixar and a few other studios to go hang, but when a young aspiring filmmaker from Austin named Erik Horn, who had no money and was looking to make his first feature, got in touch to ask about film rights to “Noogie’s Time to Shine,” well, there you go. “Noogie’s Time to Shine” was a pulp novel I had written in 2007. It was based on the true story of a former New York University film student turned ATM maintenance man who discovered he could siphon off a twenty here, a twenty there from the machines he was restocking without anyone noticing. When his slow-motion heist was uncovered, well, things took a sharp turn for the ludicrous.

Erik was a smart kid, he caught the obscure film references that littered the novel, and he got the jokes. We had a signed contract two weeks later.

I told Erik I wanted nothing to do with the script or the casting, that I wanted to be completely hands off. It was his movie and he could run wherever he liked with it. In response, he informed me I would be involved with the production whether I wanted to or not. I mistakenly assumed this meant I would be receiving regular email updates.

As a blind, cranky 50-year-old drunk, I never imagined that in 2014 I would find myself climbing into a ramshackle van with four kids in their 20s to make a madcap road trip from Miami to New York City to grab some second-unit shots. I also couldn’t imagine flying from NYC to Austin in August to hang around as the movie was being filmed. This meant a week of sweaty 18-hour days as the small crew shot all the scenes they could at one location, then packed up and zoomed to the next location to set up again. They had a very tight shooting schedule, so this process was repeated three or four times a day.

“Noogie’s” production was strictly out of the Roger Corman school of low-budget filmmaking: no money, first-time actors, a tiny crew, improvised sets and props and lots of hit-and-run guerrilla shooting. It was very punk rock. What struck me was this: for all the running, exhaustion and lack of pay, there was almost no palpable stress on the set and no clashing egos. All these kids seemed to be having a good time.

Every now and again, Erik would pause to add up all the laws they had broken to get the film made. It was a bunch. As one of the cameramen put it while sitting on the roof of a moving car to get some shots in downtown Savannah, “Just do what you want until someone tells you to stop.”

“Noogie” had a $35,000 budget (half what it cost to make “Detour” 80 years earlier) and took 10 years to complete. It was a decade worth of scrambling, improvising and navigating accidents. No one got busted. There were some close calls but nobody died, and the occasional small miracle manifested itself. “Noogie” premiered in Austin this March, and now it’s out there in the world, just like a real movie. It’s available on assorted streaming services, and there’ll be a smattering of theatrical screenings around the country. Who could’ve imagined? A decade after filming their scenes, several of “Noogie’s” stars — just kids at the time — have gone on to bigger things. Brandon Potter (Noogie) now stars as the villain on the TV series “The Chosen,” Lee Eddy (Det. Stone) was in Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” and Sanjay Rao (FBI Agent Meyers) stars in Richard Linklater’s latest, “Hit Man.” Again, who could’ve imagined?

It may not be “Lawrence of Arabia,” but it wasn’t intended to be. It was made precisely the way it needed to be made. I never held that “Noogie’s Time to Shine” was anything more than a silly little pulp novel. Likewise, no one involved in the picture ever thought it was anything more than a goofy no-budget caper comedy with a dash of visual va-va-voom. At times, Erik, Brandon and Brad Parrett’s script veered far afield from the novel, but that’s okay. The core story is still there and, more important to me, they captured the spirit of the book. I doubt I would be saying that if I had knuckled under and gone for that studio money.

As career moves go, it was probably pretty stupid on my part. I didn’t make a dime, but it was an adventure that turned out to be more fun than sitting through story conferences with feeble-minded corporate flacks. I may be a blind, cranky now-60-year-old drunk, but because I opted for insane tomfoolery over a whopping check, I can still live with myself.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.