Part 4: Restarting Life in a Halfway House

The transition from convict to parolee can be difficult, with more restrictions in the reintegration facility than in prison. But thoughts of the free world keep the author going.

By Ronald W. Pierce

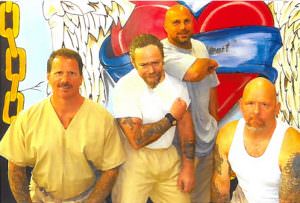

Ronald Pierce with his family (from left to right): nephew Kristopher, sister Robin, nephew Raymond, mother, and Karen, his fiancée. (Ronald W. Pierce)

Editor’s note: This is the third story in a seven-part series exclusive to Truthdig called “Going Home.” Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 5, Part 6 and Part 7.

I get up before sunrise. It is my last day in prison. I check everything. I make a strong cup of coffee. I scarf down a small bowl of cereal. I’m a ball of emotions. I’m excited. I’m nervous. I’m anxious. I can’t wait to leave. I check my watch repeatedly.

The wing officer cracks open the door at 7:22 a.m.

“Ronald Pierce,” he says. “It’s time to go.”

My heart leaps to my throat. After 30 years, two months and 17 days, my release date is here. I wish my cellmate well. He wishes me good luck. I say a final farewell to those I pass in the cells on my way out.

The Department of Corrections transports me in handcuffs, belts and shackles even though I am on parole. It’s one last humiliation. The dog kennel I’m in has seat belts this time. The officer does not buckle them. They are one more discomfort. The buckle digs into my tailbone. The cuffs cut into my wrists.

There are several men in the van. Some are going to medical visits. Some are transferring to other prisons. My thoughts drift to Latiff, who is in the Logan Hall halfway house. He’ll spend 21 days there, but he’s out. He’s working. He’s starting his life. I look forward to the transition.

We are transferred to another kennel van.

The van comes to a stop. The door opens. I’m inside a compound with high cyclone fencing topped by coils of razor wire. I feel entombed. My heart sinks. The handcuffs and shackles are removed. A guard walks me into the facility. I try to be positive. I remind myself this is temporary. It’s only temporary.

My prosthetic shoulder sets off the metal detector. All my personal documents—medical records, birth certificate and temporary ID—are taken from me. Just like in prison. The processing is much the same. Someone takes my mugshot.

I am referred to as a resident, not an inmate, during the strip and frisk. Despite the difference in wording, I still feel like a prisoner. But this time I am in a private facility instead of a public one.

My fiancée, Karen, and my mother will soon know I am here. I’ll get an opportunity to call home.

I have money in my pocket. This is a foreign feeling. I am allowed to have up to $35 to spend on vending machine purchases. The machines mostly have junk food. I don’t spend any of the money. I count my $5 bills every day. I am fearful the amount might somehow change. I examine the intricate strokes on each bill. The bills look like works of art.

Phone calls cost a dollar per minute. In a state prison, they cost 5 cents a minute. Karen is working two jobs. My mother is retired and lives on a small fixed income. I decide to write letters. No computer kiosk. No email.

The halfway house programs consume my weekdays from 9 in the morning until 2:15 in the afternoon. There is always a morning meeting. During the meeting, parolees perform a skit. The skits address issues such as addiction and employment.

The morning meeting is followed by reading “selected” news of the day. We mostly read horoscopes, sports scores and weather reports.

There is no intellectual stimulation. I miss my books. Those of us in the college program in Rahway used to have philosophical and historical debates. I want to discuss the Orlando shooting during one of our morning meetings. It reminds me of the devastation my own actions caused. But we can only discuss sports, entertainment and news items chosen by the staff.

Counselor announcements come next. The day ends with an inspirational quote.

We attend class on anger and stress management. We have a job interview class.

Most of these classes cover subjects I have reviewed several times throughout my 30 years in prison. I tell myself that review is a healthy way to improve my understanding.

In the life skills class, we watch a video about cancer patients preparing to die. Many of us cry. I’m not sure how this fits in with life skills. It does help us connect with our ability to be empathetic.

A young man has an outburst in our anger management class. I see my former self in him. Volatile. Unreasonable. His anger seems foreign to me. I will never be that person again. I feel relief that I have changed. I feel sorry for the young man. I know the long struggle he must face.

I find a Liberace quote in my Bits and Pieces pamphlet: “Nobody will believe in you unless you believe in yourself.”

What will you do to enhance the belief in yourself? How will the guy in the mirror feel about your actions today?

There is constant noise in the halfway house. Everyone is talking.

Ronald Pierce, a former Marine, is shown here with Ronnie Long, another former Marine, under an image of the Marine Corps flag. (Ronald W. Pierce)

We have more restrictions in this facility than in prison. I make a request to put the name of a friend on my visitors list. My request is denied. I make a request to put the name of a pastor on my list. My request is denied. Only my immediate family is allowed to visit. But they are not able to come.

I have been isolated for three decades.

The price of phone calls makes it impossible to talk to family and friends. Why do I remain isolated from the world I will enter in six months?

Karen says if residents in Logan Hall in Newark can go out to work after 21 days, why am I subjected to different conditions? I haven’t any answers.

Seating in the mess hall is assigned. I am forced to sit across someone who does not brush his teeth or wash his clothes. Rules cannot be questioned. We must blindly follow staff orders.

“Tuck in your shirt,” a staff member yells at me.

I tuck in my shirt.

We are berated and scolded as if we are children.

I turn 58. I do not have my family. There is no celebration. It is a lonely day. I treat myself to a birthday muffin from the vending machine.

Karen is my rock. I haven’t held her since February. She does not want to come to Trenton after work in the dark because of the crime there.

I will suffer alone for another 70 days.

I wash my new black jeans by hand, like I do all my clothes. I am afraid they will be stolen in the laundry room. Karen bought these clothes for me when I was granted parole. I do not want anything to happen to them.

We have not had mail for two days. No one complains. I feel anxious. I have not received my birthday cards. I have not received my Zetia or nitroglycerin that I use for my chest pains. There is utter indifference to our medical needs. I have heart disease. I ask for my medication every day. I’m told they will have to order it again.

I wake up at 6 a.m. My thoughts are racing. The nurse refuses to give me the Nitrostat prescribed by the doctor.

There are those who have dirty urine and need addiction treatment. There are nonviolent drug offenders. There are long-term offenders who need help reintegrating into society. The long-term offenders are the lowest priority for getting help.

The life skills class is canceled. We leave the lecture hall so the room can be searched. Several people have their names called out. The staff scans their hands.

If you write grievances, you are targeted for demerits. Too many demerits get you sent back to prison. Every day brings further despair.

I will miss my niece’s wedding. I have missed most of this young lady’s life. She asked my younger brother to give her away. He has been a part of her life. I understand. But missing the wedding rocks my foundation.

I missed my baby sister’s wedding. My friend and motorcycle-club brother, Chico, brought her a rose from me. I see the rose in her wedding pictures. I feel like I’ve been excommunicated.

I think a lot about the free world. Memories resurface after decades. I miss the little things most. I think about eating ice cream with Karen on a couch. I think about what it will be like to escape the constant control. I wonder how much of prison I will carry within me when I get to the outside.

Part 5 of the “Going Home” series will be published on Truthdig on Sunday.

Ronald W. Pierce served 30 years, eight months and 14 days in New Jersey prisons for murder. Released in 2016, Pierce now is living in Jackson, N.J., and completing his Bachelor of Arts study at Rutgers University. He is an honors student, majoring in justice studies with a minor in sociology.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.