Part 2: Welcome to Prison, and Rediscovering Humanity

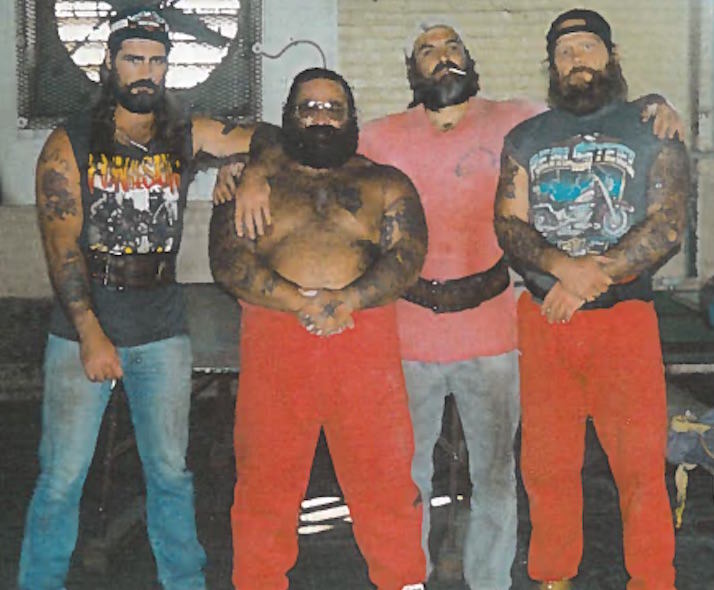

After receiving a 30-year minimum life sentence for murder and an additional seven years for armed robbery, the author learned to use his energy in a positive way while serving time in New Jersey penitentiaries. Ronald W. Pierce, second from right, with other inmates at Rahway State Prison in the late 1990s. (Ronald W. Pierce)

Ronald W. Pierce, second from right, with other inmates at Rahway State Prison in the late 1990s. (Ronald W. Pierce)

By Ronald W. PierceEditor’s note: This story is the second part of a seven-part series exclusive to Truthdig called “Going Home.” Read Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6 and Part 7.

Mike and I spent several months in the same wing at Hudson County’s Pavonia Avenue Jail. After Mike made a deal to testify, I was moved to another wing because I was facing the death penalty. I was sentenced to life with a 30-year minimum for murder and an additional seven years for armed robbery. Mike and I did not commit armed robbery. But the police chief suggested we would get a more lenient sentence if we claimed we had.

I learned my fate on Oct. 19, 1987. After two weeks of orientation in the prison reception unit in Yardville, I was sent to Trenton State Prison.

In 1989, I joined a bikers group in prison that consisted of independent bikers who had friends in the Hells Angels, Pagans and Breed. The group was set up to end biker wars in prison.

I became its chapter president. After the group’s founder, Desperado, was freed, I became its national chairman. The prison administrators considered us a prison gang.

I was able to receive some college credits in Trenton through Pell Grants. But in 1993, President Bill Clinton discontinued the grants. I earned my paralegal certificate and started working in the law library. I received my real training in criminal law from two older paralegals, George and Lloyd.

In January 1992, I got into an altercation with another prisoner in the mess hall at Trenton State. One of his friends tried to intervene, and one of my friends jumped on him. Within minutes, two groups of prisoners were in a brawl. The guards broke it up.

I received 30 days in the hole, plus 210 days in administrative segregation (ad seg), at Rahway State Prison (now called East Jersey State Prison), a maximum-security prison. Rahway’s ad seg facility is known in prison slang as the “Red Roof Inn”—because its red roof (which has been changed to blue) could be seen outside the walls of Rahway, and the facility had air conditioning, so some inmates did not care if they went on a vacation to the ad seg building for the summer. I was housed in a cell next to a man who beat his imaginary girlfriend for imagined slights to his manhood most of the day. In the cell on the other side was a man who coated the walls with his feces.

I began to ask questions in ad seg. I wondered why I could not cope with prison. I woke up one morning and looked long and hard into the mirror. I did not recognize the man in the reflection. Reflected back I saw all the men I had ever fought. I saw a man who inflicted pain because he was bigger and stronger than others. I saw a man who demanded respect through intimidation and fear. I saw a man who craved blind obedience. I saw the figures of authority in my past—my father, my mother, my high school principal, my drill sergeants and officers, and those who bullied me as a boy. I saw a man so cold he should not be allowed to be a father.

I broke down. I asked forgiveness from my unborn child. I felt I was not good enough to make his mother want to bring him into the world.

I knew I had to find my way back to my humanity.

I was sent back to Trenton.

I wrote to my Uncle Robert, telling him for the first time what had happened to me as a boy. My uncle and I had shared passions, including motorcycles and hunting.

My uncle gave the letter to my father, who proved to be uncharacteristically understanding. My father and I began to rebuild our relationship. I began to consider leaving the bikers organization.

I was transferred to Rahway in 1996. There were more rehabilitation programs at Rahway.

I was not allowed to work in the law library because I was considered a leader of a prison gang. I got the clerk’s job in the recreation department. On March 4, 1998, the prison rounded up the leadership of five supposed gang organizations. We were transferred to the Security Threat Group Management Unit (STGMU), also known as the gang unit, at Northern State Prison in Newark, N.J.

I was in the gang unit with the heads of the Latin Kings, the Netas, the Five Percenter Nation, and two designated Aryans, one of whom was, in fact, Native American.

I attended various programs in the gang unit for 11 months, including programs for culture sensitivity, addiction to violence and anger management. Then I was released from the STGMU and sent back to Rahway.

I left the prison biker group.

My belongings, which had not been sent with me to STGMU, were now inspected and returned to me. Among them was a weightlifting belt decorated with biker artwork.

I assumed that if the prison had a problem with the belt, the guards would have confiscated it during the initial inspection. But because of that belt, I was charged with possessing STG paraphernalia and was sent back to the gang unit for four months.

It took me eight months to go through the program the second time. I had done nothing wrong—not that this matters in prison, or, often in the courts—and was angry over having to go through the program again.

One day, the head of the programming division pulled me aside. He asked why I didn’t use my leadership qualities toward a positive goal.

I ignored him, but his words burned. In March 2000, I was released from the STGMU, after completing their socialization indoctrination, returned to Rahway, which by this time was referred to as East Jersey State Prison.

I started educating people about HIV prevention. I had lost family members to HIV, and on an unconscious level, I wanted to use my natural talents for good. I put all my energy into this work, the same way I used to focus on being a biker.

I was assigned a social worker, Elisa. She helped me use my energy in a positive way.

We worked on my personal growth. I told her about the sexual abuse I had experienced. I slowly tore my old self apart. I fought to be compassionate. I worked to care. I wanted to be able to feel.

In the early morning hours of Feb. 25, 2004, the housing unit I lived in caught fire. More than half of us were displaced. I, along with 29 others, was sent to Northern State Prison.

We had had a close call with death, and I was surprised by how easy it was for me to speak about my fear. A change was happening. I was starting to be able to be vulnerable and was beginning to feel a sense of self-worth. I spent 18 months in Northern before returning to East Jersey State Prison.

On Nov. 30, 2006, I received a Christmas card from Karen, the woman I dated for a blink (but did not think I was good enough for, so I did not call her again). I was glad to hear from her. I sent a card back. We began corresponding regularly, and I began experiencing feelings that I once thought only existed in fables. I felt it was possible to free myself from the emotional cage that had confined me since childhood. Life was beginning again.

I enrolled in as many prison programs as I could. I started seeing someone else in the mirror. I started seeing someone I liked.

Part 3 of the “Going Home” series will be published on Truthdig on Friday.

Ronald W. Pierce served 30 years, eight months and 14 days in New Jersey prisons for murder. Released in 2016, Pierce now is living in Jackson, N.J., and completing his Bachelor of Arts study at Rutgers University. He is an honors student, majoring in justice studies with a minor in sociology.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.