Part 3: The End of Incarceration

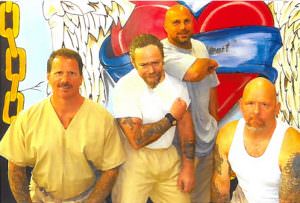

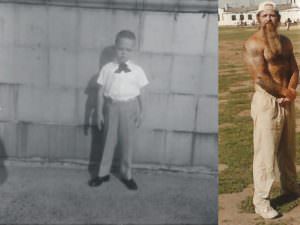

The author gets his day before the parole board after more than 30 years in prison for murder. Ronald Pierce, right, spent more than 30 years in New Jersey penitentiaries before his release in 2016. (Ronald W. Pierce)

Ronald Pierce, right, spent more than 30 years in New Jersey penitentiaries before his release in 2016. (Ronald W. Pierce)

By Ronald W. PierceEditor’s note: This is the third story in a seven-part series exclusive to Truthdig called “Going Home.” Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6 and Part 7.

I am preparing to go to breakfast. It is March 20, 2016. The wing correction officer comes to my cell. He tells me to report to the star sergeant. My mouth goes dry. I will appear before the parole board after 31 years in prison for murder.

I have three days of stubble. My khaki uniform is wrinkled from the prison laundry. Two transport officers are waiting for me. There is no time to eat. My stomach is flipping kittens. I am not thinking about food. I am placed in the chair that examines body cavities for contraband. I am escorted into the strip room. I remove my clothing. I hand my clothes to the officer who inspects them. My body is searched for contraband. My feet are shackled. My hands are cuffed and belted to my side.

I am walked to the “dog kennel,” a vehicle similar to the police van Freddie Gray was so badly injured in after being arrested in Baltimore in 2015 that he soon died. It has no seat belts. You hold on to a strap between your legs to keep from being thrown against the van’s metal walls. Why we do we call it the dog kennel? The Humane Society would never let a dog be transported in such a death trap. Over the years I refused to take medical trips in the dog kennel. I feared hurting myself. I chose not to jeopardize my life for medical procedures such as physical therapy after joint replacement surgery, stress tests for my heart condition and other tests. However, for parole, the risks equaled the rewards. Anxiety riddles through me the moment I enter the van. I sit sideways on a metal bench with skid-resistant material. I am facing a metal wall a foot-and-a-half from my face. I strain to grab the strap as the handcuffs bite into my wrists. The padlock of the belt stabs into my back. The van pulls away from the prison.

The trip to New Jersey State Prison (formerly Trenton State Prison) takes 45 minutes. My nerves are peeking. My stomach is grumbling and is tied into knots. My focus wanders. I question every choice. I didn’t feel ready for the hearing. Maybe I should have practiced in mock hearings. I have not prepared a closing statement. I am trying to go through everything in my mind. My thoughts run amok in a sea of disconnected thoughts. My heart starts racing when we reach the familiar prison walls. I worry I will have another heart attack. I don’t want to disappoint my family and my fiancé, Karen. I don’t want them to think the government is right to deny me parole. I don’t want them to think I am unfit to live in society.

The van backs into the darkened mouth of the beast. I resolve that I will not be what they portray me to be. I will make my case with all my ability. The officers open the outer van door. Then they open the kennel door. I step down into the garage. The time for doubt is over.

I go through processing. It is the same processing I endured at Rahway but in reverse. I am unshackled. I have to strip and expose for inspection each of my body cavities, including my mouth and anus. There is a complete body inspection under my arms, behind my ears, under my testicles and the bottom of my feet. This process is to ensure I did not somehow manage to get contraband planted on me during my ride in the dog kennel. After this process, I get dressed. I sit in the body cavity search chair to complete the processing procedure. I then am taken to a holding cell.

Thomas Renahan enters after five minutes. He sits on the bench across from me. He tells me he is a member of the parole board. I worry he has come to tell me it is all a mistake, and the board would not see me. I worry I will receive a Future Eligibility Term, or FET, meaning your parole has been denied in the mail. Instead, he gives me an addendum to the record for the parole board and an overview of the hearing. He tells me that if I need a break or to use the restroom, to look over at him. He will ask for a recess.

When he leaves, I begin to prepare myself to listen to the truths of my life and answer questions that will determine my fate. People I do not know will decide where my body will reside in the future.

I go into the hearing room. There are four long tables arranged in a square. The 13 board members introduce themselves. There are three others in the room, sitting in the gallery. The rumor in prison is that one is a psychiatrist, one is a body language expert and one is a voice inflection expert. The three people in the gallery supposedly assist the board in its deliberations.

One by one the board members begin to ask questions. This takes approximately three hours. They have done their homework. I begin to believe they know more about me than I know about myself. Their questions are sharp and specific. Some of the questions are pointed, some designed to lead me on, some an obvious trap door. Some ask follow-up questions about an answer I give to another board member. There are so many questions I cannot remember, although I remember them telling me not to tell them what I think they want to hear.

“If I were sitting where you are and you were here, what is the one question you would ask me that I have not asked you?” a board member asks.

I think for a moment. I say this is a good question. I contemplate my answer.

“What can I look at in your record that will give me the confidence I need to know that if I give you my vote, I will not come to regret it?” I say.

“That’s a good question,” the young, well-dressed African-American board member says. “Now answer it.”

I tell them about the prison programs I was involved in. I talk about the change in my patterns of behavior, about my emotional growth, maintaining minimum (security) status, holding the same job for over a decade, good disciplinary records and reports over the course of my incarceration.

“I don’t hear you talk about remorse,” says a white male board member who is thickset and has salt-and-pepper hair and a mustache.

“I not only took a man’s life. I took away any decision he could have made from that day until this,” I say. “I shattered the lives of his family. I denied society the contributions he might have made. I feel remorse. I devastated my family. I brought shame to them through my horrendous act. I exacted a huge cost from society. What I did had a ripple effect. It negatively affected many people.”

The questioning ends.

The chairman asks if I have any closing remarks.

“I want to thank the board for its time and consideration,” I say. “I know how busy you are.”

When that one board member asked me what question I would ask, I had thought of answering, “What would you say if you were in front of Wayne’s (the victim’s) family?” My answer would have been “nothing.” I would be afraid that my voice would cause them more pain. I would answer their questions. I would let them decide the direction of the conversation. This is what I am thinking.

I thank them again for listening. I am taken back to the holding cell to await their decision.

I go over every response I’d given. I can’t sit still. I pace back and forth. It seems like I am in the holding cell for 10 or 15 hours although it is only 10 or 15 minutes. The officers come to get me from the holding cell after the 15 minutes. I make the long walk back to the visit hall from intake. It seems like an eternity. My stomach is in butterflies. It feels as if there is a flock of geese in there.

I walk into the room. I look toward the table about 25 feet away where I had been sitting. I see a long green sheet of paper in front of my chair. When you get a FET it is printed out on a long green sheet of paper. Your parole has been denied. Appealing this decision takes one or two years. My legs become weak. My body begins to shake. My mouth goes dry. My heart sinks. I walk sluggishly to the chair. I wonder how much longer I will be incarcerated before I have another parole hearing. Will I ever see my mother again? Her age and health are not in our favor. Will Karen stay with me through more years of separation and at what cost to her well being?

I sit down. I look at the paper on the table. I focus on the words. It reads: “Notice of Release.”

My eyes fill with tears. The room begins to spin. The chairman explains the conditions of the decision. I am unable to focus on his words. I want to scream, “Thank you!” I want to promise them that they will never regret their decision. I barely can manage a whispered “Thank you.” I walk out of the hearing room. I mouth the words “Thank you” to Mr. Robinson, one of the two members who gave me the opportunity to see the full board. I am emotionally overwhelmed.

I want to get back to Rahway so I can email Karen. I tell myself on the ride back that I will keep the news to myself until I get her response. There are many people awaiting my return to find out how it went, especially the other students in the NJ-STEP college program.

I can’t contain myself. I get back in time to go to class. It is Western Political Theory with professor Chris Hedges. I am supposed to give a presentation on Chapter 10 of Sheldon S. Wolin’s “Politics and Vision: The Age of Organization and the Sublimation of Politics.”

“I am not focused or prepared to give my presentation,” I say. “I went to the full board for my parole hearing. I am being paroled.”

The class bursts into applause.

Part 4 of the “Going Home” series will be published on Truthdig on Saturday.

Ronald W. Pierce served 30 years, eight months and 14 days in New Jersey prisons for murder. Released in 2016, Pierce now is living in Jackson, N.J., and completing his Bachelor of Arts study at Rutgers University. He is an honors student, majoring in justice studies with a minor in sociology.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.