On the Move

Since the 1985 publication of “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat," neurologist Oliver Sacks has been enlightening readers with sharply observed, generously humane medical case studies. In his latest book, "On the Move: A Life," Sacks presents an extended study of the patient he knows best: himself. Knopf

Knopf

Knopf

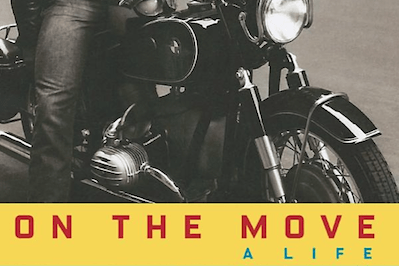

“On the Move: A Life” A book by Oliver Sacks

For 30 years, since the 1985 publication of “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” neurologist Oliver Sacks has entertained and enlightened readers with his case studies of patients, each one sharply observed and yet generously humane. Now, in his latest book, Sacks presents an extended case study of the patient he knows best: himself.

Like the other individuals the doctor has examined, the subject of “On the Move” is an intriguing and often puzzling specimen. Afflicted with prosopagnosia, or face blindness, and sometimes-crippling shyness, Sacks is also a devoted therapist and an affectionate friend (the title of the book comes from a poem by his longtime friend Thom Gunn). An intellectual full of passionately esoteric interests, working on the fringe of mainstream medicine, Sacks has also found a secure niche in American popular culture, being played by Robin Williams in the well-known movie “Awakenings.” And lest you think you know him already (Sacks has often written about himself in books including “A Leg to Stand On,” “Uncle Tungsten” and “The Mind’s Eye”), be assured that this case history holds many surprises.

The first one can be found right on the book’s cover, which bears a photograph, taken in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1961, of a brawny, leather-jacketed young man astride a motorcycle. It’s an image as far as one can imagine from today’s slight and diffident neurologist, but this was indeed Oliver Sacks, age 28. Having concluded that “there were too many Dr. Sackses in London” (his mother, father, brother, uncle and three cousins were all physicians practicing in the city), Sacks left his native England after medical school and settled in America, mostly in New York but first in California.

The freedom and pleasure he found on the West Coast infuse the early chapters of “On the Move” with a delicious freshness: We hear of boisterous weightlifting contests at Muscle Beach in Venice, where he was nicknamed “Dr. Squat” after lifting an eye-bulging 575 pounds, and of meditative motorcycle rides to the Grand Canyon: “I would ride through the night, lying flat on the tank; the bike had only 30 horsepower, but if I lay flat, I could get it to a little over a hundred miles per hour, and crouched like this, I would hold the bike flat out for hour after hour,” Sacks recounts. “Illuminated by the headlight — or, if there was one, by a full moon — the silvery road was sucked under my front wheel, and sometimes I had strange perceptual reversals and illusions. Sometimes I felt that I was inscribing a line on the surface of the earth, at other times that I was poised motionless above the ground, the whole planet rotating silently beneath me.”

The lyricism of Sacks’ account is interrupted only by the frequent inclusion of excerpts from his letters home or from his early attempts at travel writing: These are forced and overblown, at pains to please and impress. Here is Sacks writing to his mother and father while on the road in British Columbia: “In all the churches prayers are said for rain, and god knows what strange rites are practiced in private to make it come. Every night lightning will strike somewhere, and more acres of valuable timber conflagrate like tinder. Or sometimes there is just an instantaneous apparently sourceless combustion arising like some multifocal cancer in a doomed area.”

Such stilted and self-conscious interludes make the reader all the more appreciative of the lucid writing style Sacks later developed, a style that turns out to be as well-suited to autobiography as it is to the medical case study. When describing his patients and their problems, he is attentive and precise, straightforward and sympathetic, and he brings these worthy qualities to his descriptions of his younger self. “I never had much intellectual self-confidence, even though I was regarded as bright,” he writes. Upon receiving his medical degree, he relates: “I was excited, but I was terrified too. I felt sure I would do everything wrong, make a fool of myself, be seen as an incurable, even dangerous bungler.” There is no trace of vanity in these pages; Sacks is especially — almost stunningly — frank about his fumbling efforts to explore his homosexuality, at a time when being gay (Sacks first heard the word on a trip to Amsterdam in the mid-1950s) was widely reviled and gay sex was against the law. His adored mother tells him that he is “an abomination,” painful words he struggles to get past: After a welcome but brief encounter on his 40th birthday, he confesses, “I was to have no sex for the next thirty-five years.”

Sacks is just as humble when describing his professional path. He started out with dreams of becoming a bench scientist, but in a series of hilarious “errors” (Sacks the therapist would surely place that word in quotation marks), he repeatedly made a mess of his research projects, losing or throwing away his records or the experiments themselves. On his way to work at the Bronx State Hospital one morning, for example, he failed to tie his lab notebook tightly enough to his motorcycle rack: “My precious notebook, containing nine months of detailed experimental data, escaped from the loose strands and flew off the bike while I was on the Cross Bronx Expressway. Pulling over to the side, I saw the notebook dismembered page by page by the thunderous traffic. I tried darting into the road two or three times to retrieve it, but this was madness, for the traffic was too dense and too fast. I could only watch helplessly until the whole book was torn apart.” Soon afterward, he screwed the lens of his microscope through several irreplaceable slides, then lost a biological sample it had taken him 10 months to extract (“perhaps I swept it into the garbage by mistake”).

Finally his supervisors had had enough. “Sacks, you are a menace in the lab,” he was told. “Why don’t you go and see patients — you’ll do less harm.” After failing at research, he discovered his gifts as a clinician and a writer.

Yet even here, the road was not smooth. At a moment when the case study — as ably practiced by The New Yorker’s Atul Gawande and Jerome Groopman, for example — is a staple of magazines, newspapers and books, it’s surprising to learn how much resistance Sacks encountered when he first began writing in the genre. To be sure, he did not invent the form: He was consciously emulating the writer-physicians of the 19th century, such as Jean-Martin Charcot and William Richard Gowers, whose work he so admired. But the melding of scientific expertise and vivid storytelling that Sacks wished to practice had fallen out of favor in modern medicine, and his early efforts met with silence and even disapproval.

Eventually, of course, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” became an acclaimed best-seller. Though gratified by the many letters from readers, Sacks had mixed feelings about his new success: “For better and for worse, with ‘Hat’s publication, I became a public figure, with a public persona, even though by disposition I am solitary and venture to believe that the best, at least the most creative, part of me is solitary. Solitude, creative solitude, was more difficult to come by now.”

As his autobiography moves into his more recent, more famous years, it too dulls a bit. At the same time, these late chapters acquire an urgent new poignancy for readers aware of the news: Sacks is gravely ill. In an article published in The New York Times in February, he revealed that he has advanced cancer, a disease that began as a tumor of the eye and has now spread to his liver.

It’s a turn that is almost too much like a case study by Oliver Sacks. His stories often concern people who’ve suffered a loss central to their identities — the writer who wakes up one day unable to read, the painter who can no longer discern color — and here we’re presented with the quintessential observer, made blind in one eye by his illness. Sacks’ cancer is terminal, but he vows to keep going as long as he is able: In addition to his autobiography, he noted, he has “several other books nearly finished.”

He never was the kind of doctor to promise miracle cures (though he did occasionally deliver them, as when he “awakened” patients from a decades-long state of catatonia with the drug L-dopa). For 30 years, he has been telling us — gently, kindly — that while medicine can ease our pain and even provide insight, there’s ultimately no fix for the human condition. We, and he, can only observe and record it, as honestly and vividly as possible, right up to the end.

Annie Murphy Paul is the author of “The Cult of Personality,” “Origins” and the forthcoming “Brilliant: The Science of How We Get Smarter.”

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.