Justice for Eric Garner: Street Protests and Prosecutions Will Not End Police Brutality

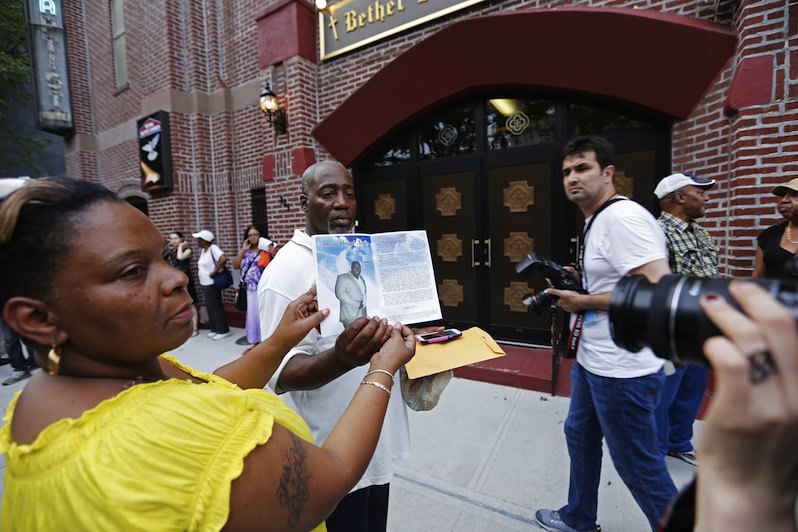

"I can't breathe" was one of the last things 44-year-old Eric Garner said after being arrested by New York Police Department officers and placed in what appears, in a bystander's video, to be a chokehold. A woman holds a remembrance of Eric Garner at a funeral service for Garner in New York City on July 23. Shutterstock

A woman holds a remembrance of Eric Garner at a funeral service for Garner in New York City on July 23. Shutterstock

“I can’t breathe” was one of the last things 44-year-old Eric Garner said after being arrested by New York Police Department officers and placed in what appears, in a bystander’s video, to be a chokehold. The asthmatic African-American man was being detained on suspicion of illegally selling cigarettes on the sidewalk and died shortly after being taken into custody. With the city medical examiner ruling his death a homicide, it remains to be seen if the cop-friendly Staten Island district attorney will prosecute the law enforcement officers.

In another case that resulted not in death but trauma and severe humiliation, a 48-year-old woman in Brooklyn named Denise Stewart, also African-American, was dragged by male officers out of her apartment while she was clothed in only a towel and underwear. They were looking for the source of a domestic violence call that had been made from somewhere in the building and heard shouts coming from Stewart’s unit, but she told officers they had the wrong apartment. Stewart, who, like Garner is asthmatic, was left topless and screaming in desperation for her oxygen. Although she survived the encounter, she has now been charged with assaulting a police officer, and her son and two daughters have also been slapped with charges.

Both police encounters are attracting public outrage but perhaps only because they were videotaped by witnesses. In Garner’s case, Ramsey Orta, whose video of the arrest provides the clearest indication of what happened, has himself been arrested on unrelated weapon possession charges. Orta’s arrest has the potential to have a chilling effect on witnesses documenting such police encounters.

Although the federal government carefully tracks the number of law enforcement officers who are killed and assaulted annually, there is no nationwide record of how many people die or are injured at the hands of police officers, despite a requirement issued by Congress in 1994 for the U.S. attorney general to do just that. That fact itself is an indication of the value that our government places on the lives of police officers over ordinary people. It may also be an indication that if accounts were kept, the numbers might be too staggering to ignore.

In the absence of government statistics, individuals are attempting to track deaths. One former FBI agent named James Fisher counted a total of 1,146 people shot by police nationwide from Jan. 1, 2011, to Jan. 1, 2012, with 607 of them dying. A journalist named D. Brian Burghart, the publisher and editor of the Reno News & Review, has started his own online searchable database called Fatal Encounters to “be able to figure out how many people are killed by law enforcement, why they were killed, and whether training and policies can be modified to decrease the number of officer-involved deaths.” Burghart’s site offers state-by-state searches, and a comparative database of incidents. Wikipedia also maintains a list of officer involved killings organized by date and location but it is nearly impossible to verify the completeness of these lists without a comprehensive and detailed study.

Yet those of us who constantly monitor the news understand the ubiquity of police abuse. We see and feel it all around us, sometimes in our own neighborhoods, and all too often through personal experience. Depending primarily upon our race, but also on income, gender and age, it is often fear of police officers, rather than trust in their uniform, that colors our comfort levels with them.

Racial profiling and excessive police force are a potentially fatal mix. When I see a police car in my rearview mirror, my instant and irrational reaction is one of panic, while my white friends are probably more likely to hold the attitude of “if you haven’t done anything wrong, there’s nothing to fear.” I find myself constantly making the mental calculation of whether a police officer will judge me by my skin color or by the fact that I’m driving a Prius — an unmistakable hallmark of the middle class that could mitigate any officer bias.

Black and brown Americans especially know how some police officers tend to view them through the lens of race above all. Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge David S. Cunningham found that even his exalted position, and his former leadership of the L.A. Police Commission, did not protect him from police abuse on the UCLA campus. The university agreed last month to pay $500,000 to settle a suit over an arrest of Cunningham in November that he says was made solely because of his race (he is African-American). Arizona State University’s Ersula Ore similarly seemed to find that being a professor on the campus she was walking through apparently did not trump the fact that she is black when she was stopped for jaywalking in May and asked for ID by police, in an incident that resulted in a charge of resisting arrest and a sentence of nine months’ supervised probation.

A recent report by the ACLU called War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing analyzed police data from 20 agencies around the country in 2011, and found that 62 percent of SWAT team deployments were for drug searches and 79 percent were to serve search warrants. But in only 35 percent of the heavily armed deployments was a weapon even present in the searched home, and 54 percent of the people impacted were people of color. The stories profiled in the ACLU report are tragic, with severe injuries and even deaths caused by open fire or flash-bang grenades. In May, a SWAT team burst into the Wisconsin home of Alecia and Bounkahm Phonesavanh and set off a grenade that landed in the crib of their 19-month-old baby nicknamed Bou Bou, severely injuring him and covering his body with third-degree burns. Alecia, a white woman whose husband Bounkahm is Laotian, said, “This is about race. You don’t see SWAT teams going into a white collar community, throwing grenades into their homes.”

Occasionally we get glimpses of how police officers themselves view the people they are supposed to “protect and serve.” In rants said to be by anonymous police officers reacting to Garner’s death, the pervasive theme is that the heavyset man deserved to die. Several people who posted comments used epithets such as “assholes,” “savages,” “fat bastard” and “fat fuk” to describe Garner and others like him. A Huffington Post collection of police T-shirts sporting abusive messages is also indicative of a disturbing culture among law enforcement officers; my favorite is a cartoon drawing of a wide-eyed toddler behind bars with the slogan, “U raise ’em, we cage ’em.”

Given the pervasive public skepticism of police, it should have come as no surprise to the NYPD when an attempt to launch a social media campaign went horribly wrong earlier this year and revealed just what some New Yorkers think of their police department. A call by the department for Twitter users to post photos of themselves with police officers using the hashtag #MyNYPD resulted in an outpouring of damning photos and videos of officers engaged in what appears to be brutal behavior.

More tangible than “hashtag activism” has been the traditional progressive response to police brutality: street protests and agitation for citizen oversight of police departments. In New York, activists called for the immediate charging of Daniel Pantaleo, the officer involved in Garner’s arrest. They have also criticized New York Police Chief William Bratton’s so-called broken windows approach to urban policing that focuses on petty crimes. Bratton brought his model to New York after trying it out in Los Angeles, another big city rocked at various times by numerous scandals involving police brutality. Elsewhere in California, actions in two cities — Anaheim in 2012 and Salinas in May — over the police involved killings of several Latino men have also triggered rallies and marches.

Part of the reliance on street protests arises from the frustration over how rarely police officers are ever found guilty of assault, homicide or any type of misconduct within our justice system. A recent article from Texas reported that until recently not a single police officer in Dallas had been charged with shooting civilians in 40 years, let alone convicted. There are similar statistics across the state and likely the nation.

Clearly neither protest nor prosecution has had enough of an impact in curbing police brutality. So what can we do, short of living in perpetual fear of cops?

One answer may lie in the unlikely city of Albuquerque, N.M., where a years-long series of officer-involved fatal encounters that even the U.S. Justice Department has condemned in a major report has sparked a communitywide response. In addition to a relentless procession of marches and protests that range from traditional to creative (such as an occupation of the mayor’s office), activists have taken a proactive approach. A group called Protect and Serve ABQ has decided to re-envision what the relationship between a community and its police force should look like, through solicitations of testimonials and concrete ideas. It remains to be seen whether its approach will have an impact.

But perhaps there are even simpler solutions, which, if implemented in departments nationwide, could begin to slow down police abuse. The Police Foundation, a group dedicated to “advancing policing through innovation and science,” conducted a yearlong study of police officers in Rialto, Calif., who were given “body-worn” video cameras that they had to use during working hours. Researchers found a whopping “50% reduction in the total number of incidents of use-of-force compared to control-conditions.”

Britain also offers a tantalizing approach. There, police officers rarely carry firearms, and when they do use them, the shootings are immediately investigated and each police-related death makes big news. In the year 2011-2012, officers shot guns only five times, and only two people were killed. Compare this to Fisher’s number of more than 1,000 people shot in the U.S. during roughly the same time period.

Currently the lack of nationwide statistics on police brutality is accompanied by a lack of standards by which police behavior is assessed and addressed. If the lives of Americans who have died at the hands of police officers are worth anything, we need to do more than just march in the streets or call for prosecution.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.