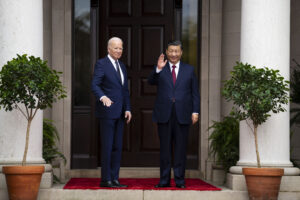

Is Trump Headed for War With China?

Sooner or later, if the president doesn’t dial down his rhetoric on China, its leaders will surely ratchet up theirs. Thomas Roggero / CC-BY-2.0

1

2

3

4

Thomas Roggero / CC-BY-2.0

1

2

3

4

As Marina Tsirbas, a former diplomat now at the Australian National University’s National Security College, explains, Beijing’s written and verbal statements on the South China Sea lend themselves to two different interpretations. The Chinese government’s position boils down to something like this: “We own everything — the waters, islands and reefs, marine resources, and energy and mineral deposits — within the Nine-Dash Line.” That demarcation line, which incidentally has had ten dashes, and sometimes eleven, originally appeared in 1947 maps of the Republic of China, the Nationalist government that would soon flee to the island of Taiwan leaving the Chinese Communists in charge of the mainland. When Mao Ze Dong and his associates established the People’s Republic, they retained that Nationalist map and the demarcation line that went with it, which just happened to enclose virtually all of the South China Sea, claiming sovereign rights.

This stance — think of it as Beijing’s hard line on the subject — raises instant questions about other countries’ navigation and overflight rights through that much-used region. In essence, do they have any and, if so, will Beijing alone be the one to define what those are? And will those definitions start to change as China becomes ever more powerful? These are hardly trivial concerns, given that about $5 trillion worth of goods pass through the South China Sea annually.

Then there’s what might be called Beijing’s softer line, based on rights accorded by the legal concepts of the territorial sea and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which took effect in 1994 and has been signed by 167 states (including China but not the United States), a country has sovereign control within 12 nautical miles of its coast as well as of land formations in that perimeter visible at high tide. But other countries have the right of “innocent passage.” The EEZ goes further. It provides a rightful claimant control over access to fishing, as well as seabed and subsoil natural resources, within “an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea” extending 200 nautical miles, while ensuring other states’ freedom of passage by air and sea. UNCLOS also gives a state with an EEZ control over “the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations, and structures” within that zone — an important provision at our present moment.

What makes all of this so much more complicated is that many of the islands and reefs in the South China Sea that provide the basis for defining China’s EEZ are also claimed by other countries under the terms of UNCLOS. That, of course, immediately raises questions about the legality of Beijing’s military construction projects in that watery expanse on islands, atolls, and strips of land it’s dredging into existence, as well as its claims to seabed energy resources, fishing rights, and land reclamation rights there — to say nothing about its willingness to seize some of them by force, rival claims be damned.

Moreover, figuring out which of these two positions — hard or soft — China embraces at any moment is tricky indeed. Beijing, for instance, insists that it upholds freedom of navigation and overflight rights in the Sea, but it has also said that these rights don’t apply to warships and military aircraft. In recent years its warplanes have intercepted, and at close quarters, American military aircraft flying outside Chinese territorial waters in the same region. Similarly, in 2015, Chinese aircraft and ships followed and issued warnings to an American warship off Subi Reef in the Spratly Islands, which both China and Vietnam claim in their entirety. This past December, its Navy seized, but later returned, an underwater drone the American naval ship Bowditch had been operating near the coast of the Philippines.

There were similar incidents in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2009, 2013, and 2014. In the second of these episodes, a Chinese fighter jet collided with a US Navy EP-3 reconnaissance plane, which had a crew of 24 on board, less than 70 miles off Hainan island, forcing it to make an emergency landing in China and creating a tense standoff between Beijing and Washington. The Chinese detained the crew for 11 days. They disassembled the EP-3, returning it three months later in pieces.

Such muscle flexing in the South China Sea isn’t new. China has long been tough on its weaker neighbors in those waters. Back in 1974, for instance, its forces ejected South Vietnamese troops from parts of the Paracel/Xisha islands that Beijing claimed but did not yet control. China has also backed up its claim to the Spratly/Nansha islands (which Taiwan, Vietnam, and other regional countries reject) with air and naval patrols, tough talk, and more. In 1988, it forcibly occupied the Vietnamese-controlled Johnson Reef, securing control over the first of what would eventually become seven possessions in the Spratlys.

Vietnam has not been the only Southeast Asian country to receive such rough treatment. China and the Philippines both claim ownership of Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal/Huangyang Island, located 124 nautical miles off Luzon Island in the Philippines. In 2012, Beijing simply seized it, having already ejected Manila from Panganiban Reef (aka Mischief Reef), about 129 nautical miles from the Philippines’ Palawan Island, in 1995. In 2016, when an international arbitration tribunal upheld Manila’s position on Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal, the Chinese Foreign Ministry sniffed that “the decision is invalid and has no binding force.” Chinese president Xi Jinping added for good measure that China’s claims to the South China Sea stretched back to “ancient times.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.