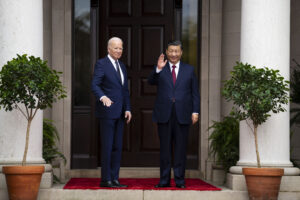

Is Trump Headed for War With China?

Sooner or later, if the president doesn’t dial down his rhetoric on China, its leaders will surely ratchet up theirs. Thomas Roggero / CC-BY-2.0

1

2

3

4

Thomas Roggero / CC-BY-2.0

1

2

3

4

Then there’s China’s military construction work in the area, which includes the building of full-scale artificial islands, as well as harbors, military airfields, storage facilities, and hangars reinforced to protect military aircraft. In addition, the Chinese have installed radar systems, anti-aircraft missiles, and anti-missile defense systems on some of these islands.

These, then, are the projects that the Trump administration says it will stop. But China’s conduct in the South China Sea leaves little doubt about its determination to hold onto what it has and continue its activities. The Chinese leadership has made this clear since Donald Trump’s election, and the state-run press has struck a similarly defiant note, drawing crude red lines of its own. For example, the Global Times, a nationalist newspaper, mocked Trump’s pretensions and issued a doomsday warning: “The U.S. has no absolute power to dominate the South China Sea. Tillerson had better bone up on nuclear strategies if he wants to force a big nuclear power to withdraw from its own territories.”

Were the administration to follow its threatening talk with military action, the Global Times added ominously, “The two sides had better prepare for a military clash.” Although the Chinese leadership hasn’t been anywhere near as bombastic, top officials have made it clear that they won’t yield an inch on the South China Sea, that disputes over territories are matters for China and its neighbors to settle, and that Washington had best butt out.

True, as the acolytes of a “unipolar” world remind us, China’s military spending amounts to barely more than a quarter of Washington’s and U.S. naval and air forces are far more advanced and lethal than their Chinese equivalents. However, although there certainly is a debate about the legal validity and historical accuracy of China’s territorial claims, given the increasingly acrimonious relationship between Washington and Beijing the more strategically salient point may be that these territories, thousands of miles from the U.S. mainland, mean so much more to China than they do to the United States. By now, they are inextricably bound up with its national identity and pride, and with powerful historical and nationalistic memories — with, that is, a sense that, after nearly two centuries of humiliation at the hands of the West, China is now a rising global power that can no longer be pushed around.

Behind such sentiments lies steel. By buying some $30 billion in advanced Russian armaments since the early 1990s and developing the capacity to build advanced weaponry of its own, China has methodically acquired the military means, and devised a strategy, to inflict serious losses on the American navy in any clash in the South China Sea, where geography serves as its ally. Beijing may, in the end, lose a showdown there, but rest assured that it would exact a heavy price before that. What sort of “victory” would that be?

If the fighting starts, it will be tough for the presidents of either country to back down. Xi Jinping, like Trump, presents himself as a tough guy, sure to trounce his enemies at home and abroad. Retaining that image requires that he not bend when it comes to defending China’s land and honor. He faces another problem as well. Nationalism long ago sidelined Maoism in his country. As a result, were he and his colleagues to appear pusillanimous in the face of a Trumpian challenge, they would risk losing their legitimacy and potentially bringing their people onto the streets (something that can happen quickly in the age of social media). That’s a particularly forbidding thought in what is arguably the most rebellious land in the historical record. In such circumstances, the leadership’s abiding conviction that it can calibrate the public’s nationalism to serve the Communist Party’s purposes without letting it get out of hand may prove delusional.

Certainly, the Party understands the danger that runaway nationalism could pose to its authority. Its paper, the People’s Daily, condemned the “irrational patriotism” that manifested itself in social media forums and street protests after the recent international tribunal’s verdict favoring the Philippines. And that’s hardly the first time a foreign policy fracas has excited public passions. Think, for example, of the anti-Japanese demonstrations that swept the country in 2005, provoked by Japanese school textbooks that sanitized that country’s World War II-era atrocities in China. Those protests spread to many cities, and the numbers were sizeable with more than 10,000 angry demonstrators on the streets of Shanghai alone. At first, the leadership encouraged the rallies, but it got nervous as things started to spin out of control.

“We’re Going to War in the South China Sea…”

Facing off against China, President Trump could find himself in a similar predicament, having so emphasized his toughness, his determination to regain America’s lost respect and make the country great again. The bigger problem, however, will undoubtedly be his own narcissism and his obsession with winning, not to mention his inability to resist sending incendiary messages via Twitter. Just try to imagine for a moment how a president who blows his stack during a getting-to-know-you phone call with the prime minister of Australia, a close ally, is likely to conduct himself in a confrontation with a country he’s labeled a prime adversary.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.