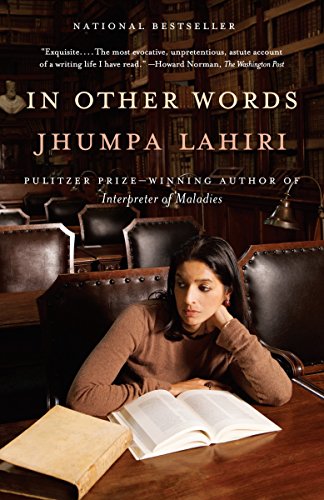

In Other Words

Novelist Jhumpa Lahiri's evocative memoir is written in her third language, Italian. "I'm in another dimension," she writes of working in Italian, "where I have no references, no armor. Where I've never felt so stupid."

“In Other Words” A book by Jhumpa Lahiri, translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein To see long excerpts from “In Other Words” at Google Books, click here.

Jhumpa Lahiri lived with her family in Rome in 2012. Though she had studied Italian for 20 years, as part of her “full immersion” into the Italian language, she now kept a kind of philological notebook, full of vocabulary, phrases, rules of grammar. Initially, some of this was shaped into an essay in the magazine Internazionale. And now we have the memoir, “In Other Words,” which Lahiri, one of the most intellectually elegant novelists in the world, composed in Italian. The English translation by Ann Goldstein (translator of “The Complete Works of Primo Levi” and Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet) participates in an exquisite duet across the page with Lahiri’s Italian. Strikingly honest, lyrical, untouched by sentimentality, “In Other Words” chronicles as philosophical and quotidian a courtship with a language as Ovid’s “The Art of Love” does with amore itself.

Italian is Lahiri’s third language. Her formative language is Bengali, but when her family moved to the United States, she made the adjustment to using English. Decades later, her books — “Interpreter of Maladies,” “The Namesake,” “Unaccustomed Earth” and “The Lowland,” all written in English — have entered the highest echelons of literary regard.

Lahiri refers to her unmitigated desire to learn Italian as a “self-imposed exile.” Here she writes about the psychological, even clandestine effects of such cultural displacement: “When you live in a country where your own language is considered foreign, you can feel a continuous sense of estrangement. You speak a secret, unknown language, lacking any correspondence to the environment. An absence that creates a distance within you.”

“In Other Words” is the most evocative, unpretentious, astute account of a writing life I have read. In part, this is because Lahiri so unabashedly asks and answers big and vexing questions: “Why do I write? To investigate the mystery of existence. To tolerate myself. To get closer to everything that is outside of me.”

In Rome, speaking in Italian was inextricably bound with writing in Italian, all of which made for an exceedingly difficult apprenticeship. Feeling mortified when her teacher exactingly critiques her first short pieces, Lahiri writes, “I’ve never tried to do anything this demanding as a writer. I find that my project is so arduous that it seems sadistic. I have to start again from the beginning, as if I had never written anything in my life. But, to be precise, I am not at the starting point: rather, I’m in another dimension, where I have no references, no armor. Where I’ve never felt so stupid.”

“I write to feel alone,” Lahiri declares, which speaks to the paradox of being a writer to begin with, notably one who has tens of thousands of readers in many languages. In interviews, Lahiri has extolled the virtues of anonymity whenever she can return to Italy, sit in a cafe, line up espressos and talk with her neighbors.

Yet in lovely and profound ways, “In Other Words” is a family story, one dealing with the vicissitudes and unpredictable blessings of relocating husband and children to a different world, with how memories are constructed, with the enervating sense of life as makeshift. For its treatment of such experiences, Lahiri’s memoir belongs on the same shelf as Anthony Doerr’s “Four Seasons in Rome.”

The chapter “The Wall” begins with Lahiri stating, “There is pain in every joy.” There follows, in a shop in Salerno, a somewhat cringe-worthy yet indelible scene: “My husband’s name is Alberto. For him, it’s enough to extend his hand, to say, ‘A pleasure, I’m Alberto.’ Because of his looks, because of his name, everyone thinks he’s Italian. When I do the same thing, the same people say, in English, ‘Nice to meet you.’ When I continue to speak in Italian, they ask me: ‘How is it that you speak Italian so well?’ and I have to provide an explanation, I have to say why. The fact that I speak Italian seems to them unusual. No one asks my husband that question.”Lahiri is typically frank about the deeper insistences that compelled her to move from Brooklyn to Rome: “I’m reminded of a passage in Verga, whom I recently discovered: ‘To think that this patch of ground, a sliver of sky, a vase of flowers might have been enough for me to enjoy all the happiness in the world if I hadn’t experienced freedom, if I didn’t feel in my heart a gnawing fever for all the joys that are outside these walls!’? The speaker is the protagonist of La storia di una capinera (Sparrow: The Story of a Songbird), a novice in an enclosed order of nuns who feels trapped in the convent, who longs for the countryside, light, air.

“I realize that the wish to write in a new language derives from a kind of desperation. I feel tormented, just like Verga’s songbird. Like her, I wish for something else — something that I probably shouldn’t wish for. But I think that the need to write always comes from desperation, along with hope.”

The great Czech writer Milan Kundera not only wrote his most recent novels in French, but rewrote earlier ones in French. This he called “an opportunity for renewal of the spirit.” Whether or not Lahiri chooses to write her future books in Italian, what matters is not linguistic provenance but the quality of the prose. Words like “enduring” and “indispensable” should be saved for only the rarest literary achievements, and the memoir “In Other Words” is one of those.

Howard Norman’s most recent novel is “Next Life Might Be Kinder.”

©2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.