Leslie Jamison’s Kaleidoscope of Loneliness

Essays feature a whale with online followers, families who believe a child led a prior life and Civil War photographers’ staging of corpses. Leslie Jamison. (YouTube Screenshot)

Leslie Jamison. (YouTube Screenshot)

Years back, I read Leslie Jamison’s brilliantly conceived book of essays, “The Empathy Exams,” and was attracted to her scorching and original voice that circled around the rough edges of female pain, rage and powerlessness while zeroing in on her own. Jamison’s father left when she was a young girl.

Her older brother had already left for college, and her beloved younger brother was getting ready to go. All the men were leaving. Sadness, confusion and vulnerability were already her steadiest companions. By the time she was 8, she had already developed a taste for champagne sweetened with spoonfuls of sugar.

Other obsessions soon took hold. She was starting to starve her already thin body, and would occasionally cut thin lines into her ankle, taking pleasure in the pain. She started messing around with boys early, and established a destructive pattern of being with one man after another. Cocaine and other drugs followed.

One day in a small town in Mexico, a man punched her hard in the face and grabbed the digital camera around her neck. She fled back to Los Angeles for extensive surgery to repair her severely disfigured face. She soon got pregnant but aborted the fetus. Her drinking binges swung out of control. In 2010 she took herself to AA and the initially rocky path to sobriety began. During all this, she managed to graduate from Harvard and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and got a Ph.D. from Yale in literature. But these credentials did not soothe her demons.

Jamison’s turbulent and self-destructive early years made me think hard about two pieces of her recent writing I found. One is about her mother:

It was just the two of us. We made vegetarian Sloppy Joes for dinner. We watched “Murder, She Wrote” on Sunday nights, eating our two bowls of ice cream side by side. … In many photos from my childhood, she is embracing me—one arm wrapped around my stomach, the other pointing at something, saying, look at that, directing my gaze toward ordinary wonders. To talk about her love for me, or mine for her, would feel almost tautological; she has always defined my notion of what love is. … Trying to write about my mother is like staring at the sun. It feels like language could only tarnish this thing she has given me my whole life—this love. For years, I’ve resisted writing about her. Great relationships make for bad stories. Expression naturally gravitates towards difficulty. Narrative demands frictions, and my mom and I live—by the day, the week, the decade—in closeness.

The other piece is about Amy Winehouse. When Jamison watched Winehouse perform, she saw someone whose heart was breaking into pieces as she sang.

Jamison was already seven years sober when she wrote this piece, but watching Winehouse on film with empty bottles of booze surrounding her made her “remember what it had felt like to be unsober—gloriously, unapologetically unsober: drinking whiskey by a bonfire, feeling the sluice of heat down my throat, its rhyme with the flames at my fingertips. … I remember how the prospect of sobriety seemed like unrelenting gray, after luminous, disjunctive nights—a bleak horizon, a shirt washed so many times it had lost all its color. What could the straight line of on the mend hold that might rival the dark, sparkling sweep of falling apart?”

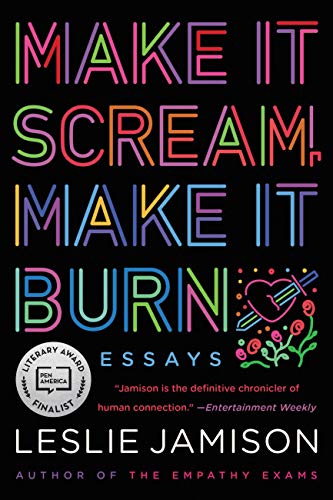

These two passages seem to be a prequel to Jamison’s masterful new collection of essays, “Make It Scream, Make It Burn.” How could such a loving mother raise a girl who wanted to do nothing more than destroy herself? Jamison’s ability to capture this essential contradiction is her secret power as an artist.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Make It Scream, Make It Burn” at Google Books.

“52 Blue,” the first essay in “Make It Scream, Make It Burn,” is about a huge whale with whom researchers have become obsessed. All male whales moan at a certain decibel to find mates, but 52 Blue, as he has been named, does so at an incredibly loud decibel—and no other whale seems to answer his exuberant call. No one has ever seen him, but he has accumulated a host of loyal online followers who track his whereabouts, perhaps seeing in him a metaphor for their own loneliness.

One woman, Lenora, woke up unsteady and unsettled after surgery for a severe intestinal blockage and the coma that followed. Her friend’s brief visits left her feeling helpless. She started following 52 Blue online: “Like the whale, she felt that her own language was adrift. She was struggling to come back to any sense of self, much less find the words for what she was thinking or feeling. The world seemed to be pulling away, and the whale offered an echo of this difficulty. She remembers thinking, ‘I wish I could speak whale.’ She found a strange kind of hope in the possibility that 52 knew he wasn’t alone.”

In “We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live Again,” Jamison spends time with families who believe one of their children has led a prior life. At first, the cynic in Jamison resists their stories, which seem beyond rational belief. She thinks these parents and their children are engaging in some sort of elaborate charade. But as her inquiries deepen, so does Jamison’s empathy for these families. At the time she was researching this piece, she was heavily involved “in a twelve-step recovery program for more than three years. I’d found that its grace required extinguishing, or at least suspending many forms of skepticism at once: about dogma, about clichés, about programs of insight and prefabricated self-awareness, about other people’s ostensibly formulaic narrative of their own lives. In recovery, we were asked to avoid ‘contempt prior to investigation’ and writing a piece about reincarnation … seemed like a different test of this willingness to keep an open mind.”

Instead of castigating these families for their possible deceptions, Jamison claims it is more important to focus upon what these deceptions were offering these families, which she describes as an “articulation of faith in the self as something that could transform and stay continuous at once…”

Jamison understands the immense power of deception to move us. One of the best essays in the collection, “No Tongue Can Tell,” is about Civil War photography. Jamison learns that many of the most revered shots of the Civil War’s carnage were staged. Limbs and corpses were artistically arranged against backdrops chosen by photographers. She writes, “Conspicuous forms of distortion, however, only force us to confront the truth that all photos are inevitably mediated, inevitably constructed, inevitably distancing.”

While visiting a museum exhibiting Civil War photographs, she finds herself unmoved, her focus on how the photographers micromanaged the images they produced. Only one shot grabbed her. It was a framed portrait of three elaborately dressed dead men in full military gear seeming to stand proudly, the middle one with his eyeballs missing. This shot got through to her, not the rows of pictures showing battlefields filled with bloated corpses and weapons. She finds out afterward that the man with no eyes was a Union soldier named William R. Mudge, a Massachusetts native, and a photographer before the war.

Another engaging story, “Maximum Exposure,” is about Annie, an American photographer who spent almost three decades following an impoverished family in a shantytown in Mexico, while photographing some of their most intimate moments.

These pictures appear throughout the essay. The family eating supper while looking past one another silently. Dazzling laughter between a mother and one of her children in a spontaneous moment of affection. The father sitting on a bus staring threateningly into Annie’s camera as if it were a weapon.

Annie chronicled her experiences with the Mexican family in multiple journals, speaking of times she helped the family with money and other times when she refused. Her journals spoke about her need to be close to them, but also her desire to flee, which she often did, only to return again. Annie wrote of the lingering guilt that she was stealing their most precious resource: the relationships they had with one another. Jamison writes, “The language of photography conjures aggression and theft. You shoot a picture. You take a photograph. You capture an image or a moment. It is as if life—or the world, or other people, or time itself—has to be forcibly plundered or stolen.”

Both Annie and Jamison are drawn to the drama of ordinary people who struggle to survive on the margins. They are both interlopers of a sort, women from privileged backgrounds who are free to come and go as they please. And they recognize that their elevated status mars the empathy they seek with others from different worlds, regardless of the intimacies that might sometimes develop for a time. They will eventually return to their own world of choice and free agency. It is a devil’s bargain.

In the final essays of the book, Jamison turns the narrative lens upon herself and her present life as a teacher, mother, stepmother and wife in Park Slope, Brooklyn, where she juggles family life and her career with an enthusiasm she never guessed possible.

Mostly, she seems to rejoice in the daily pleasures life serves up. The strange delights of sobriety. The dailiness of work and love. Scrambled eggs at the diner with her husband while a babysitter watches their children. There are insecurities about stepparenting that she struggles with. And times the desire to be alone overtakes her. But she doesn’t want to run away. She wants to be present. She wants to embrace the messiness of family life head-on. Her narrative voice has shifted from her earlier work; it is less dark but it is no less daring, powerful and innovative. She is a writer at the peak of her powers, sharing with us the hard-won reflections of a woman who has finally decided to let some light in.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.