How the Big Awakening Became a Hangover

Chile's new constitution failed. Now its leftist president is trying to reignite hopes for change. Chile's President Gabriel Boric is seen through a light fixture as he listens to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz during a ceremony at the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

This is Part I of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

Chile's President Gabriel Boric is seen through a light fixture as he listens to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz during a ceremony at the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

This is Part I of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

March 11 marks the first anniversary of the inauguration of Gabriel Boric, the bearded and tattooed 37-year-old millennial president of Chile. The leader of the first leftist government since the overthrow of Salvador Allende in 1973, Boric is a former university protest leader who rose to power outside the traditional party system after a “social explosion” in 2019 that violently redrew Chile’s political map. His election seemed to augur a period of deep political reform, a “second peaceful revolution” that would resume the one initiated by Allende, for whom I served as a translator until the coup forced me to flee the country.

Upon my return to Santiago in January, it didn’t take long to understand that Chile had taken a different course, and that the reform process had entered a downcycle. “Right now, there’s a disenchantment with politics and social mobilization – a very bad hangover,” Hassan Akram, a professor and former adviser to Boric’s campaign, told me inside the studio where he broadcasts a radio and YouTube show called “The Voice of Those Left Behind.” Located a few blocks from the national palace, the studio buzzed with 30-something members of Akram’s alternative media collective, busy with preparations for the expected arrival of the day’s guest, the feminist social scientist and first lady of Chile, Irina Karamanos, 33.

“If social mobilization is cyclical, this is the low point,” says Akram. “The peak was in 2019.”

Something in his voice told me he didn’t think it was supposed to turn out this way.

How did plans for a peaceful social and political revolution get bogged down, delayed and perhaps, dead-ended in the space of a single year? How did a political agenda that began with a focus on environmental, economic and social justice become ensnared in debates about crime, immigration and inflation? Understanding this would become the focus of my trip, displacing my original hope of witnessing the restoration of the transformational project I saw cut violently short half a century ago.

The Social Explosion

Early on Oct. 25, 2019, Chileans began to gather in Santiago’s central Plaza Italia. They sang, danced and chanted slogans such as “Chile Despertó!” or “Chile has awakened! By mid-afternoon, more than a million Chileans were standing in the streets – an historic mass that covered the plaza and its surrounding areas and backed up two miles down the main Alameda boulevard to the La Moneda presidential palace. It was what some old-time revolutionaries called a “festival of the oppressed.” The event had no formal leadership and had no political parties at the helm. If “the biggest march in Chile’s history” had a through-line, it was opposition to “neoliberalism.” The word meant different things to different people, but a shared understanding of its costs inspired a protest that shook the Andean nation of 19 million to its foundations.

Thirty years of civilian government after the end of the Pinochet dictatorship in 1991 had brought a fair share of democracy, and until 2016, rapid economic growth that lifted millions out of extreme poverty. At the same time, Pinochet’s harsh and savage neoliberal economic program was modified, not dismantled and yawning economic and social gaps continued to grow, making Chile one of the most unequal countries in the developed world. According to one United Nations study, the top 1 percent currently controls 25 percent of the country’s wealth. Education, social security, electricity, sanitation and even water remain privatized. The average retirement pension hovers at $250 a month, barely half the minimum wage. Mass consumerism has flourished, much of it leveraged on readily available credit cards and installment plans that have created widespread economic stress. Thousands of human rights cases from the Pinochet era remain unresolved. Three decades of civilian rule have lifted expectations just enough to produce mass disillusionment and disappointment, scorn for all the traditional parties and a sense of exclusion. It was no accident that marchers on Oct. 25 chose “The Dance of Those Left Over,” the signature song of Los Prisioneros, an old rock-protest group, as their anthem.

Adding to Chile’s tinderbox was the then-incumbent government led by right-wing billionaire Sebastian Piñera, stocked with the country’s indifferent elite. Piñera’s administration provoked the ire of millions by announcing that while food had gotten expensive, flowers were still cheap; that if a schoolhouse needed a new roof, maybe it was time for a bingo fundraiser; and if workers didn’t like recent subway fare increases, they should get up two hours earlier to beat the peak-rate fare. It was a “let them eat cake” performance by a government of cartoon plutocrats.

The marches of Oct. 25 marked an escalation of protests that had begun weeks earlier, when high school students began jumping the turnstiles in protest of a 4 percent hike in subway fares. While the increase was minimal, it was enough to ignite three decades of pent-up frustration and humiliation among broad sectors of the population. The events unleashed in October 2019 have come to be known as The Social Explosion.

It was a “let them eat cake” performance by a government of cartoon plutocrats.

“The explosion was a combination of economic frustration, exclusion from quality education and efficient health services, mixed with a rejection of the political system itself,” says Felipe Aguero, a political scientist at the University of Chile. “Participation in elections had fallen to 40 percent, and the parties were just fine with that. They did not hide their elitist disrespect, including from the [center-left] Concertacíon alliance. The statements from Piñera’s ministers about buying flowers and getting up earlier were quite expressive, revealing an elitist government that frankly could not give a shit.”

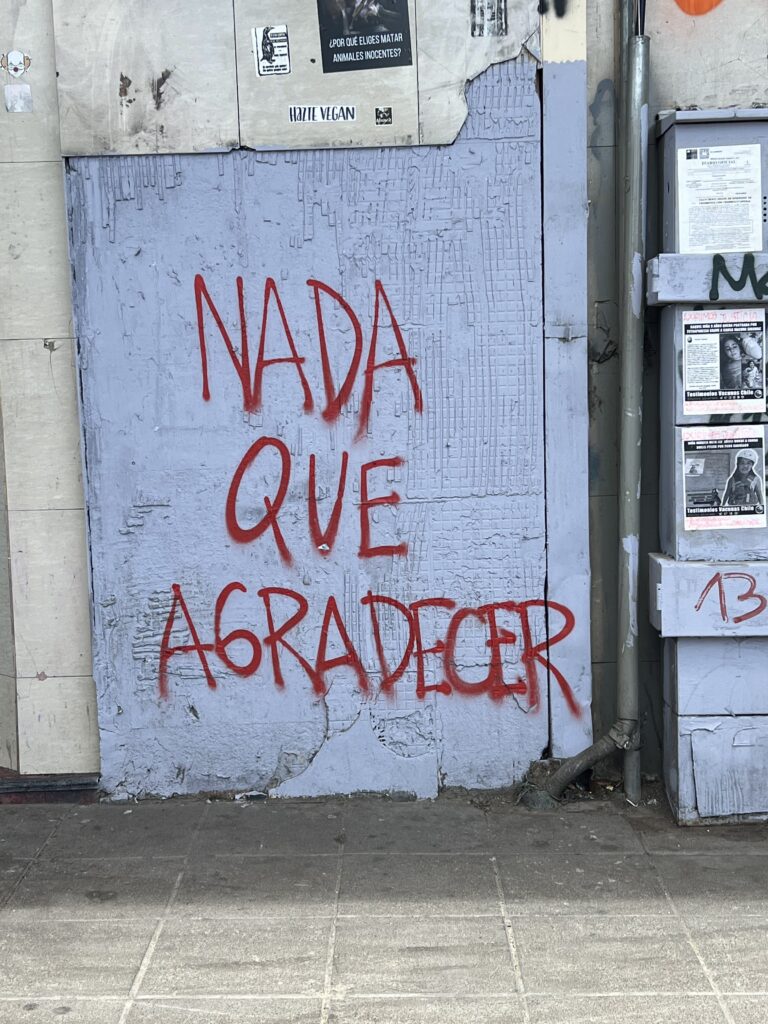

When Pinochet was voted out of power in a 1988 plebiscite, his center-left opposition came up with a jingle promising “Happiness is on the way” [as celebrated in the movie “NO”]. Thirty years later, you can find graffiti on the walls of Santiago decrying, “The happiness never arrived.” Another popular slogan that summed up the widespread rage referred to the subway fare hike: “It’s not about the 30 pesos – it’s about the thirty years.”

“The Chilean system has tried to include more and more people into the market, but not into the political system,” says Nikolas Somma, head of the Institute of Sociology at the Catholic University. “Both the right and the left have failed to provide a sense of strong political representation and have created a great distance between the society itself and the political world.” Somma underlines what he calls The Pińera Factor. “He took this detachment to an extreme,” he says. “Zero charisma, using a business lexicon. He was like a distant manager, like a Harvard-trained CEO. power points; data points, really stupid jokes about very serious issues.”

During the initial student protest, subway stations were set ablaze and some looting broke out as the rebellion, still leaderless, spread to a dozen other Chilean cities. Piñera fanned the flames by declaring a state of emergency, announcing he was now at war. He flooded the streets with soldiers, and the brutal military police, the Carabineros, proceeded to escalate the street violence.

As protesters fought police, much of downtown Santiago was trashed. Tear gas clouds filled the skies and angry graffiti – still visible today – seemed to cover every available square foot of wall space in the capital. More than 30 people were killed, and 2,500 were wounded in the social explosion. As many as 3,000 were arrested. A staggering 220 Chileans suffered damage to their eyes or were rendered blind when the police intentionally fired pellets and rubber bullets at head level. (Some 3,100 accusations of brutality, including torture, have been levelled against the police by the National Human Rights Institute. At last look, 91 percent of those allegations had not advanced procedurally, due mainly to noncooperation by the police, a reminder that the Carabineros and the Armed Forces have not been reformed since the dictatorship and still operate with excessive immunity).

Underneath the street violence, Chile was developing the seeds of a new political culture of deep civil engagement to replace the discredited system.

“Something very interesting was emerging,” historian Claudio Barrientos of Diego Portales University says. “All of a sudden we are meeting with our neighbors, talking all the time: What is better for us? What is better for Chile?

“We saw local new political organizations, which is rare in Chile, as politics is generally all centered around the state and the party elites. It felt like very big changes were coming.”

The Allende era had been rife with social movements driven underground by Pinochet, only to reemerge in the 80s to help defeat the dictatorship. But they had consistently lost potency and visibility during the 30 years of post-dictatorship government, and had pretty much exited the scene, except for periodic student-lead outbreaks.

During the weeks of the explosion, new social movements from nearly every sector had begun to re-form. Most notably, a vigorous women’s movement emerged to help lead the protests. The insurrectionary potential of the Oct. 25 march was not lost on Piñera. He canceled the fare increase and decreed some minor relief reforms, but the disruptions continued.

“All of a sudden we are meeting with our neighbors, talking all the time: What is better for us? What is better for Chile?”

Then on Nov. 15, six weeks into the uprising, Piñera put together an agreement with congress and opposition figures such as Boric for a plebiscite scheduled for the coming year. The vote would allow Chileans to choose and write a new constitution. While a constitutional rewrite was not an initial or central demand of the protesters, Piñera was aware that the current constitution, imposed by the dictatorship in 1980, was hated by millions of Chileans.

“I don’t think Piñera cared at all about the constitution,” says one prominent congress member close to Boric. “But he must have figured that it was safer to have all of us in the streets talking about a new constitution, rather than forcing his resignation or overthrowing the government.”

Protests Extinguished. Gabriel Boric Elected.

The move was only partially successful. Most protesters accepted the challenge, seeing the possibility of folding desired reforms into a new constitution. But protests stretched into 2020.

Plans were underway for even more massive rallies in spring 2020 when disaster struck. The COVID plague hit Chile like a tsunami. President Piñera responded in mid-March 2020 by instituting some of the most severe restrictions in the hemisphere. A nightly curfew was imposed. Chileans, for months at a time, were barred from leaving their homes, even to go shopping, unless a pass had been secured. Travel between regions was halted. “We were cut off from going anywhere, basically,” says a close friend of mine, a former political prisoner now living 65 miles south of the capital on a family farm. “We were prisoners in our own homes.”

As businesses were shuttered, unemployment neared 10 percent. The GDP took a wallop. A steep inflationary cycle set in – one that continues today – and Piñera allowed Chileans to raid their own social security accounts for cash on more than one occasion.

Seemingly overnight, five months of effervescent rebellion was snuffed out. Boom, like somebody had thrown a switch. Piñera used the COVID lockdown to temporarily douse the political firestorm of the previous months.

In October 2020, a year after the social explosion, the plebiscite promised by Piñera took place. Nearly 80 percent of voters approved the rewriting of the national charter; of the options available, they chose the most democratic, bottom-up process to elect the constituent assembly. The new constitution became the rallying point for a revived reform movement, a development that made world headlines.

“This was a high point,” says Akram, the analyst and activist. “A lot can be debated about the degree of politicization coming out of the social explosion. There was some consensus beyond simple slogans. And certain connections can be made between, ‘We are angry, we’re pissed off, we need a new political system, and ‘Yeah we need a new constitution that works,’” he says.

“But the primary demand of the protests was not a new constitution,” Akram says “The primary demand was ‘We want Sebastian Piñera to go.’ So when you get this 80percent vote, you can say 80 percent want a new constitution but it’s more like 80 percent said, ‘Piñera wants the old constitution, so fuck him; we want a new one.’ That vote fundamentally was a rejection of Piñera, and that first plebiscite was the height of the movement.”

As a result, the constitutional assembly’s 155 delegates were led by the most radical candidate lists, representing a kaleidoscope of social and special interest movements. The process was marked by gender parity and a number of seats reserved for the indigenous Mapuche, who make up about 10 percent of the population. It was free of tutelage from the discredited political parties; the political right was virtually excluded from the process.

This was the makeup of the “people’s assembly” that set about to write the first explicitly anti-neoliberal constitution in the world.

A Stab at Utopia

In December 2021, Gabriel Boric was elected president of Chile with 55 percent of the vote in a runoff with Jorge Antonio Kast, a marginal figure of the extreme right and an open enthusiast of Pinochet and Brazilian strongman Jair Bolsonaro. Boric, who had made his bones in 2011 as the leader of an insurgent student movement, rode the ticket of the Frente Amplio, or Broad Front, a democratic socialist coalition he helped form four years earlier that positioned itself to the left of the Concertacíon, the alliance of the Christian Democratic and Socialist parties that had exhausted themselves and lost support during the previous 30 years of civilian rule.

When Boric assumed power, his government looked like nothing Chile had seen before: a de facto generational revolution that displaced political graybeards from the center of power. Of the 24 cabinet ministers, 50 percent were women. Allende’s granddaughter was named minister of defense, overseeing the armed forces that had overthrown her grandfather. Two posts were held by the first LGBTQ ministers in Chilean history. Three of Boric’s fellow former student leaders took up cabinet posts, including Camila Vallejo, who was named government spokesperson and had already been profiled by the international press as a rising star of the small but influential Chilean Communist Party. Two-thirds of the cabinet was members of the Broad Front. A handful of seats went to a newly formed bloc, Democratic Socialism, which was basically the rump of the old Concertacíon minus the Christian Democrats; they came in as junior partners.

Though Boric lacked a majority in a narrowly divided Congress, expectations for change remained high.

Since his days as a student leader, Boric had eschewed membership in any traditional party. He passed through several smaller groupings that included democratic Socialists, left Libertarians and social Democrats. While he positioned his campaign and his government to the left of the declining Socialist Party and was comfortable in an alliance with the Communists, he defied easy categorization as representing the sectarian “hard left.”

“This is first left government in 50 years,” says University of Chile research professor and feminist activist Aznun Candida over lunch at the Café Literario, one of Boric’s favorite hangouts in the bohemian neighborhood of Nuñoa. “But they are not revolutionaries like the 60s. The political map has changed and we cannot use the cold war prism of the last century. This is the left of a new century. This is a feminist government. This is a plurinational government. This is an environmental government. It functions with a more horizontal approach than a top-down, centralized one.

The process was marked by gender parity and a number of seats reserved for the indigenous Mapuche, who make up about 10 percent of the population.

“The question is if this new left is going to be capable of managing this very difficult situation that is really a slow-motion apocalypse,” says Candida, referring to the lingering effects of the COVID crisis, inflation and the high cost of living, a spike in violent crime, an immigration crisis and a resurgent extreme right. “The government must govern well,” she says. “But there are a lot of external factors beyond [his] control.”

Boric also made it clear that the Cold War days of choosing one camp over another are long gone. No leftist leader has been more adamant in condemning the situation in nominally leftist Nicaragua, where Daniel Ortega has perverted the Sandinista revolution and built a repressive family-led dictatorship. Nor does Boric offer any praise for the authoritarian models of Cuba and Venezuela that violate his passionate commitment to democracy.

“I think Boric wanted to build a sort of Sweden in Chile,” says political scientist Roberto Funk. “Though it’s not clear Chileans want to be Sweden.”

Boric pleased his more leftist constituency by announcing the establishment of a Chilean embassy in Palestine. He enraged Chile’s Jewish community by temporarily refusing to accept the credentials of the Israeli ambassador on the same day Israeli forces killed a Palestinian boy. But Boric is much more given to talking about concrete reforms to improve the quality of life than he is railing and fulminating against “U.S. imperialism.” His big issue is dismantling neoliberalism.

Soon after taking office, the new president decreed a 17 percent increase in the minimum wage. He tacked on a small increase in the basic pension payout. But he held back on his more sweeping proposals of pension reform and tax reform – tax evasion in Chile is at epidemic levels – and chose instead to invest his political capital in supporting the process for a new constitution.

That pause, in retrospect, might have been his first major mistake.

* * *

In July 2022, just four months after the inauguration, the constituent assembly released a draft of the new constitution that would be put up to a referendum in the fall. Laden with 338 articles, it attempted to do everything for everybody who had a hand in formulating it. The proposals ran from meat-and-potato social justice and economic rights issues to proposals that might seem exotic or downright utopian. They included assigning human rights to nature; abolishing the Senate and replacing the House with ill-defined regional committees; and changing Chile into a plurinational state that recognized indigenous territory as almost a standalone nation. The draft also included gender rights, sexual rights and propositions that were foreign to most Chileans, or at best, relatively new in Chilean politics.

“It was way too much,” says Rene Rojas, a Chilean teaching at The State University of New York at Binghamton, referring to the draft charter. “There were two big categories of articles. On one side the basic social needs and rights like healthcare, education, housing, retirement to be guaranteed by the state. On the other hand, a group of more narrow identitarian social justice issues of all types: gender rights, ethnic rights, rights of nature that were all presented in a moralizing way as special protections for people suffering narrow forms of oppression – not universalist ideas. And in the campaign to approve the draft, that second set of rights that drowned out the more basic, universal ones. It inverted the national mood.”

In short, Chile had entered the greater world in the previous decades and a sort of American-like “woke” politics got grafted onto what has been more traditional concerns of class and economics and it was a mismatch.

“I am pleased that in this 21st century the issues of sex, gender, and diversity are finally part of the public and political debate,” says Candida. “The old constitution ignored those issues. The self-criticism we have to make is [that] we did not emphasize enough the economic and social rights in the new constitution. We need to find a way to match them with these cultural issues, but in a way that is not so distant from the lives of people.”

in the new constitution” – Aznun Candida / Photo by Marc Cooper

Olave, the political scientist, says, “It was a marvelous constitution, I eventually voted for it. But the way the drafting assembly was elected, the way it was written, lost all sense of negotiation and compromise. There was no outreach beyond its own constituents. And the price we are paying today for that is very high.”

The release of the draft was a bonanza for the Chilean right, which unleashed a vicious and well-funded disinformation campaign. It warned Chileans that the new constitution would lead to expropriation of their homes and vacation houses. It claimed the pension reform in the new charter would decimate private savings and the government would give that money to illegal immigrants. The loud propaganda campaign was amplified by national media that is still largely controlled by the right. To many, it resembled the so-called “campaign of terror” financed by the CIA in 1964 to blunt the rise of the Chilean left.

The conservative forces had a field day mocking the assembly while its sessions were being broadcast. While much of the work was serious and sober, there was nevertheless a circus-like aspect that fueled the ridicule. In the opening session, a dispute erupted over whether to stand and sing the national anthem or not. One high-profile delegate dressed as Pikachu, the Pokemon character. Another delegate, serving as vice president of the assembly, had campaigned for his seat with his head shaved and IVs attached to his body, claiming the Chilean health system was not treating his cancer. He later confessed to faking his illness.

After the Catharsis

As the referendum date of Sept. 4 approached, fears grew that the charter would not be approved. Those fears were born out when voters overwhelmingly rejected the constitution, with a whopping 68 percent of Chilean voters turning it down, including a surprising “no” majority from left-leaning working-class areas. The rejection – El Rechazo – hit the government, its supporters and the Chilean left like a Category 5 storm.

“It felt like a soft coup,” Akram says. Even government’s supporters believed the administration did a poor job in communicating what was positive in the draft constitution, and erred in holding back major reforms until the new charter passed.

This may have been true, but a joke that circulated in the aftermath of the defeat suggested that deeper forces were also at work in Chilean society. “You knew the constitution was going to be defeated,” it went, “when a few weeks before the vote there was an enormous line to get into the new IKEA store.”

IKEA’s popularity seemed to symbolize for many the end of the Allende period, and even the Chile of the dictatorship, when a sense of mutual aid, solidarity and community had prevailed. Now, Chile appeared fragmented, with an atomized population more interested in building a better bookcase than making sure their neighbors could eat.

* * *

Perhaps the biggest failure of the government was assuming that the energy and appetite for change on display in 2019 would carry over into and after the election. They underestimated how much public opinion had been changed by a series of profound shocks over the intervening three years: The pandemic. The lockdown. The economic crash. A wave of 500,000 Venezuelan immigrants igniting xenophobia among the Native population.

Out in the marginal, poorer neighborhoods that ring the capital, once-vibrant social movements had been displaced by a growing network of narcos that was inspiring a narco-style subculture among the youth. While Chile remains one of the safest countries in Latin America, a spike in violent crime terrified many in the nation, causing them to stay inside at night. Some analysts describe the crime surge as causing a national psychosis.

More than once, I chuckled to myself when a taxi driver or waiter decried the crime wave – minor by continental standards – by saying, “Chile has never known this kind of violence.” Unless, of course, one includes 17 years of dictatorship and state terror campaigns that involved kidnapping, murder, torture and disappearances. More recently, uniformed guardians of the law had intentionally blinded protesters.

The crime hysteria was on display my first morning in Santiago, when I arrived to find the morning news magazines and private TV networks delivering nonstop and breathless reporting on shootings, stabbings and narco traffic across the northern border. For the right, these were the political stories that mattered. Even the state-owned channel joined in the scarefest, fearful that it would lose ratings to its conservative competitors if it abstained. Also contributing to the climate of fear was the simmering conflict over land rights in the southern indigenous zone. The state of emergency declared by former President Piñera had been criticized by Boric the candidate; as president, Boric also ramped up security measures among the Mapuches.

The release of the draft was a bonanza for the Chilean right, which unleashed a vicious and well-funded disinformation campaign.

“I think we all were really naive,” says Barrientos, the historian. “We thought that all this discontent that exploded in 2019 was the beginning of a political process. And we thought that it was a process that was leading to a major change, and we put too much faith in all the millions that marched. But I think it was more a catharsis – a major expression of different identities that exploded at the same time. But that’s different than a coherent political movement. If you ask me today what is the legacy of the 2019 social upheaval, I don’t have an answer.”

Pablo Abufom, a social movement organizer, says political and institutional change is something a lot of people wanted in 2019. “But after the pandemic, people want direct improvement of their lives, not through a mediated political process,” he says.

Boric read the disastrous results of the constitutional rejection as a moment to change course. After the vote, he shifted markedly toward the center and strengthened his posture on crime. He quickly agreed to a new multi-step process to rewrite the constitution that will culminate in December. That process has been taken over by the congress, which has imposed certain boundaries on the process, ensuring that the new constitution, if approved, will include reforms and ways to protect the private sector’s participation in essential services. It will, in other words, secure a continuation of neoliberal policy where it is most injurious.

There’s growing speculation that Boric’s left constituents could torpedo the next proposed charter if it does too little to effect fundamental change. “It might be met with great abstention, mostly from the left,” says Olave, the political scientist. “In the end we will have a constitution [without] any remnant of Pinochet’s constitution, but very far from what was proposed and imagined only six months ago.”

“The rules are written so that the [new] convention deliberates with a leash, straitjacket and chaperones, making sure that it will not go rogue,” writes political scientist Patricio Navia. “The expectation is that the new constitution will be a dull document, as constitutions normally are.”

Boric’s rerouting also has led him to increase the presence and role of his junior partners – the rump of the old Concertacíon – in his cabinet, and turn over key ministries such as Interior to those who recently were viewed with some circumspect. “Boric’s Frente Amplio coalition was built to rebel against and confront the Concertacíon,” says Pablo Abufom. “But day by day, we see its role enlarged inside the government.”

by Taller Sol

It’s too early to judge the Boric government or its reform program as finished. The right remains sharply divided, as Jorge Kast’s Republicans and other right-wing populists jockey for dominance over the traditional conservative parties. They are militant and scary enough to encourage some unity on the center-left. And with the suspense over the constitution pretty much evaporated, the government can concentrate on pushing through key reforms that could bolster its popularity. It is currently focused on tax reform and pension reform bills. The tax issue is especially important for the government’s reform hopes, because without sufficient revenue, it will be impossible to fund needed expansions of social insurance programs.

Strategists close to Boric project that tax reform and possibly expanded pensions could pass this year, take effect in 2024, and be useful political capital for a 2025 election that promises a titanic fight with the right. These reforms are a long way from utopia, or even the peaceful revolution imagined by many in the streets in 2019. But they would produce meaningful improvements in the quality of life for millions of Chileans and keep the flame of deeper reforms alive. Speaking on a recent Sunday political talk show, congressman Gonzalo Winter, a close Boric ally, minced no words.

“If Chile doesn’t implement tax reform,” he said, “and if it can’t establish a new strategy of economic development as soon as possible, then that unequal country that millions mobilized against will be forever with us.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.