The Other 9/11: A Ghost Story

Fifty years after the coup, Pinochet’s legacy continues to haunt Chile. A man holds a flag with the portrait of late Chile's president Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014. The coup toppled Chilean President Salvador Allende and began the military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. (Photo: Luis Hidalgo/AP)

This is Part II of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

A man holds a flag with the portrait of late Chile's president Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014. The coup toppled Chilean President Salvador Allende and began the military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. (Photo: Luis Hidalgo/AP)

This is Part II of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

A half-century after his military coup immolated 150 years of Chilean democracy, the ghost of Gen. Augusto Pinochet continues to roil and divide the Andean country he ruled for 17 years. His legacy of human rights abuses and neoliberal economics can be seen in Chile’s extreme inequality, its unreformed and unaccountable military and police, and unresolved human rights abuses, including the fate of more than 1,000 people who were disappeared during the dictatorship and thousands more still awaiting the trial of their abusers. While there has been uneven progress in these areas since Pinochet ceded power in 1990, many features of his dictatorship remain enshrined in the 1980 constitution that Chile’s new government is attempting, and struggling, to replace. The most nefarious part of that charter is its favoring of private industry to run crucial services like education and social security. “We are trying to build a future, but we have one foot solidly trapped in the past,” says a former union organizer who spent years as a political prisoner under Pinochet. “Pinochet is dead, but Pinochetism is very much alive. We are constantly bumping into it.”

While a clear majority of Chileans look upon the Pinochet era as the darkest chapter in their history, a significant minority — as large as 40% — continues to admire Pinochet and believe that he made Chile great again, or at least tried to. This view is often held most ardently by the wealthiest Chileans who benefited the most from the annihilation of leftist parties and organizations, the suppression of unions and widespread privatization.

Many such people could be found on a recent warm Saturday morning standing in line to enter Chile’s tallest building, the 62-story Gran Torre, five stories of which are lined with the 300 designer shops and pricey eateries that populate the gleaming Costanera Center, Latin America’s biggest mall. While something like half the national population is mestizo, nearly all of the shoppers at the Gran Torre are of strict European lineage, with skin color and hair several shades lighter than most Chileans. What darker Chileans are seen at the mall carry no shopping bags, as they cannot afford the shop’s goods, such as designer tennis shoes costing $200 — the average monthly social security pension. They might as well be visiting a foreign country.

“There’s a sector of the population that will not leave their rich neighborhood even for a few hours. Anything below Plaza Italia is considered enemy territory.”

Outside the Gran Torre, a squadron of special, higher priced taxis sits waiting to ferry the shoppers to their homes in Santiago’s Barrio Alto — a belt of lush and leafy neighborhoods that resemble the manicured suburbs of West Los Angeles. These “high neighborhoods”— Providencia, Las Condes, Vitacura — are named for their placements on slight inclines near the Andes foothills. But their secondary, more common meaning of “high” or “upper” is understood by both residents and nonresidents. These enclaves are surrounded by a belt of shantytowns and a decaying downtown.

“This is really two countries,” says a community health worker with EPES, a public health NGO founded during the dictatorship. “There’s a sector of the population that will not leave their rich neighborhood even for a few hours. Anything below Plaza Italia is considered enemy territory.”

Indeed, the Plaza sits like a gateway into the eastern quadrant of Santiago, an unofficial veritable border separating the Barrio Alto from downtown and the rest of the capital.

“This giant phallus overlooking the city is like the holy temple of neoliberalism,” says a university professor, Anthony Rauld, gesturing to the Gran Torre and the Costaner Center filling its entire first six floors. He notes that construction on the building began in 2006, just steps from the military hospital where Pinochet lay dying. “My friends and I joked that this was no accident,” he says. “As the guy who imposed neoliberalism in Chile was dying, his economic legacy was being erected. Now [it] would be celebrated and preserved across the street.”

For Pinochet apologists and in the American media, the coverage of the dictatorship was always “Yes, but.” Yes, he committed excesses. But, he turned Chile into an “economic miracle” with a program of unfettered privatization and savage repression. Many continue to point to the Barrio Alto neighborhoods as proof of this “miracle,” forgetting to add that this wealthy enclave is an outlier within Chile, and that the country’s most accelerated period of economic growth began after Pinochet left power.

Chile’s conservatives, meanwhile, boast that Chile is the only South American nation to be granted “first world” status as symbolized by OECD membership. These admirers of Chile’s economy, however, fail to mention that Chile is the most unequal of all the OECD nations and ranks 35th among OECD nations based on its tax-to-GNP ratio. It is the only “first world” country where as much as 35%-40% of the population works in the informal sector. This sector is fully visible outside the Gran Torre, where a street army of darker-skinned Chileans sell trinkets and homemade empanadas.

“Chile is one of the most unequal countries in the world, depending on how you measure it,” says political scientist Hassan Akram. “The economists of the right will tell you that the situation’s improved because they [use] survey[s] that don’t capture the top 1% or 2% or 3%. Remove the very top and suddenly Chile looks much more equal than it really is.”

The unequal core of Pinochet’s economic model was left in place, enshrining Chile as the world showcase for what has become known as neoliberalism — an unfettered free-market where basic services are privatized.

In the three plus decades since Pinochet left power, Chile has made visible economic advances. Extreme poverty has been greatly reduced. Hunger and malnutrition are no longer an issue. Consumer goods are readily available and visible. Smartphones abound and satellite dishes poke from the rooftops in even the most crowded slums on the periphery.

“It can be deceiving,” says political scientist Felipe Aguero. “When we talk about a middle class in Chile, it is a precarious middle class. The Chilean middle class is much closer to the poor than the wealthy. The elites in the country absolutely hate the poor [as well as] immigrants and the indigenous.”

Whatever comforts the middle class enjoys are almost always leveraged on credit. Grocery stores offer installment plans for weekly shoppers. Restaurants offer three credit installments on the purchase of a single lunch meal. “More people now have cars and have houses, but those same people are buying bread with their credit cards,” says political activist Pablo Abufom. Indeed, cash currency is barely used anymore in Chile; even street level trinket sellers carry credit apps and card swipers.

One recent international study found that 62% of Chileans find it “difficult” to get to the end of the month compared with 36% in the rest of the developed world. Only 11% of Chileans say they can “comfortably” pay the monthly bills.

The government of Gabriel Boric was elected in 2021 vowing to put an end to neoliberalism. A massive but mostly peaceful and rather spontaneous general uprising took place in late 2019 that was a cry of protest against the previous 30 years of failed civilian government. Failed because, while it did restore democracy and institute reforms, the unequal core of Pinochet’s economic model was left in place, enshrining Chile as the world showcase for what has become known as neoliberalism — an unfettered free-market where basic services are privatized.

“Neoliberalism was implemented during a regime of terror and violence and disappearance,” says Abufom. “That leaves a mark. After all these years, there’s still fear that if you get involved in politics, you’re taking some big risks.”

Decades after Pinochet left power, the national trauma of his dictatorship continues to visibly permeate Chilean life. Consider the scene that takes place on the first Saturday of every month, across town from the Gran Torre, where small crew volunteers clean up and replace vases holding plastic flowers on an acre or so of dusty common graves marked by wooden crosses in Santiago’s general cemetery. These grounds, known as “Patio 29,” were the secret dumping ground for tortured and mutilated corpses in early years of the dictatorship. Its existence had been rumored since the late ’70s, but the first bodies were exhumed only in the late 1990’s. Those with remains that could be identified were reburied elsewhere; the rest were left where they lay as a “monument to memory.” When reports emerged that 126 victims were found stuffed into 105 coffins, Pinochet coldly quipped, “That was some great economizing.”

1,500 serious human rights cases from the Pinochet era languish in Chile’s understaffed courts, even as accusations and lawsuits continue to flow.

Fifteen years ago, the National Forensic Service misidentified scores of bodies and the process had to be rebooted, much to the bitter anguish of relatives and families. As of this writing, just over half of the bodies have been positively identified. President Gabriel Boric, now a year and half into his term leading a leftist coalition, has promised a “National Search Plan” to once and for all account for all of the disappeared — the first Chilean government to make that promise. “We have a moral duty to never stop looking,” he said recently. As of this writing, Boric is outlining the details of his search plan that will, with little doubt, meet serious resistance inside the opposition-controlled Congress.

“It’s a race against time as witnesses age and die,” says Federico Ugaz, a leading human rights lawyer “There are advances. There is no longer total impunity. But the state just does not have the resources it needs. The issue has been kept alive mostly through the work of NGO’s and relatives of the missing.”

Meanwhile, 1,500 serious human rights cases from the Pinochet era languish in Chile’s understaffed courts, even as accusations and lawsuits continue to flow. “It’s necessary to ask the Supreme Court how it is, of the 1,469 disappeared, only 317 have been found and identified,” says Erika Hennings, president of the Londres 38 human rights group that has turned a former secret police torture center into a “site of memory.”

To understand the eye-popping dysfunction that defines the Chilean judicial system, consider the case of Victor Jara, a world-renowned protest singer-songwriter who was arrested the day after the coup. He was beaten, tortured, his two hands smashed to pieces, shot 44 times, his cadaver dumped into the streets. In 2018, 86 year old retired general Hernan Soto shot himself in his home as detectives were arriving to take him to prison to serve a 25 year sentence. Though convicted along with eight other officers, it took more than five years for Chile’s highest court to actually impose the sentence.

The 50th anniversary of the Sept. 11 coup has only sharpened Chile’s profound political polarization. “Any mention of Sept. 11 today provokes a binary debate,” says Professor Aznun Candida, of the University of Chile. “For many, Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government was a period when Chile was trying to build a more just, a more equal society. That has been seen with great affection by millions. But for other sectors, on the right and center-right, that period was seen as a nightmare with chaos and hyper-inflation, and Pinochet was a hero. So, there is a double memory. One of hope and one of fear.”

A recent poll found that 36% of Chileans say the 1973 coup was justified. Remarkably, 41% of those aged 18-25 said they know nothing about the coup. About 30% of Chileans overall said the same.

While this past month has seen a kaleidoscopic outburst of activities to mark the 50th anniversary, the political class is trying to keep things from exploding and lining up along partisan lines. Right-wing parties either celebrate Pinochet’s coup or pretend to ignore it. “Let’s not continue discussing [the past],” said Eduardo Frei Tagle-Ruiz, Chile’s second democratically elected president and member of a political party that initially supported the coup. “One-hundred, 200 years from now, there will still be no official truth. That is why we look to the future.”

President Boric has weighed in several times on the meaning of the 50th anniversary and directly refuted ex-President Frei. “I am not interested in an ‘official version’,” he said during a visit to Europe. “Nothing ever justifies the violation of human rights of those who think differently, no matter who they are. If we can achieve that consensus in Chile, I will be satisfied.”

When Boric invited all political parties to sign a joint statement condemning the 1973 coup as a sign of their commitment to democracy and pluralism, the right-wing parties rejected the idea out of hand.

When Boric invited all political parties to sign a joint statement condemning the 1973 coup as a sign of their commitment to democracy and pluralism, the right-wing parties rejected the idea out of hand. Some cited the minority presence of the Communist Party in the Boric administration, saying they would never sign anything along with it. (This is odd, given that the historically moderate Chilean Communists represented the most conservative sector of the Allende coalition.)

Boric refuses to bend to the opposition and separate the coup from the dictatorship that followed. “In the Chile of Sept. 11, 1973 and the 17 years that followed, there was no war, there was a unilateral massacre,” he said recently. More pointedly, at an event memorializing Chileans who led mass protests against Pinochet in 1983, Boric landed a direct missile on the deceased leader of the extreme right National Party, Sergio Onofre Jarpa, who served as Pinochet’s feared Minister of the Interior. “It’s lamentable,” Boric said, “that he lived out his days with impunity in spite of all the outrages he committed.”

This well-deserved attack on Jarpa’s memory was applauded by members of Boric’s cabinet. Opposition figures, meanwhile, demanded an apology. When members of rightwing parties address the coup at all, it is to attack any formal denouncing of the coup and its legacy. Figures from the National and Christian Democratic parties have used their platforms in Congress to falsely claim that the military takeover was justified by Allende’s violations of the constitution. Another right wing deputy rose to describe well-documented cases of sexual abuse by Pinochet’s military—including placing rats in prisoners’ vaginas—as an “urban legend.”

In October 2019, the right-wing government of President Sebastian Pinera declared “war” on anti-government protesters. The police went wild. Twenty-nine people were killed; as many as 2,500 were injured, including more than 450 people suffering “ocular trauma” or blindness as a result of police firing pellets at their eyes. When it was over, nearly 11,000 accusations of human rights violations were lodged against the police. Three years later, barely 130 court cases have been opened, with just 16 convictions to show for them.

When Boric was elected in 2021, police reform was part of his program. But public fears, and media hysteria over rising violent crime has increased public support for laws promoted by the conservative opposition that give the police more power to use lethal force. “It’s downright Machiavellian,” says Ugaz, the human rights lawyer. “The new laws absolve the individual cop from any legal responsibility and make it institutional and that means the code of silence.”

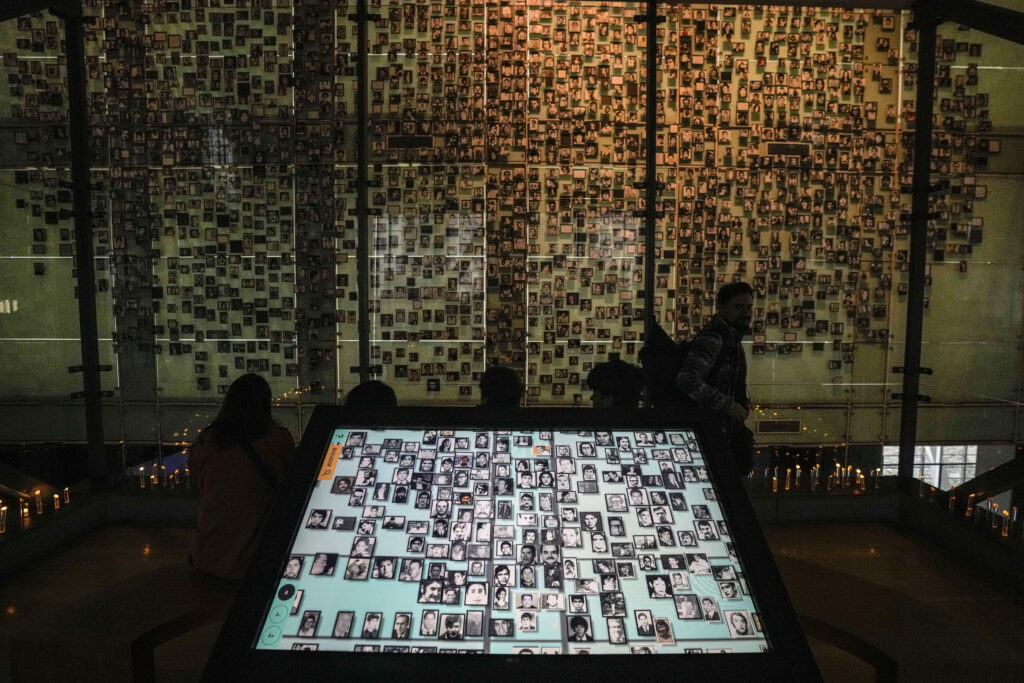

This code of silence, says Ugaz, has deep roots in the dictatorship. “It is still supreme after 50 years,” he says. “Human rights education is not as strong as it should be. It’s not taught in the schools. Yes, we have a wonderful Museum of Memory and Solidarity here in Santiago. But the number of Army soldiers who have visited it since it opened in 2010 can be counted on one hand.”

“The Carabineros remain untouched since the coup,” agrees Pascale Bonnefoy, author of a book about how plainclothes investigators helped weed out bad actors from the local police force immediately after the end of the dictatorship. “Nominally, the Carabineros are dependent on the civilian Ministry of the Interior, but they’re still independent,” she says.

High among the most frustrating obstacles to cleaning up Chile’s human rights horror, say observers, is the purposeful and deliberate lack of historic law enforcement archives.

The situation is no better when it comes to the three main branches of the military that remain immune from civilian reform. When Boric named Allende’s granddaughter minister of defense, it was understood to be mostly symbolic.

High among the most frustrating obstacles to cleaning up Chile’s human rights horror, say observers, is the purposeful and deliberate lack of historic law enforcement archives. When Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 on a murder warrant issued in Spain, the judicial ice began to crack. Until then, there had been virtually no prosecution of crimes under the dictatorship, as Pinochet had imposed an amnesty in 1979 that blocked all court actions. Some imaginative and tenacious judges ruled that the amnesty, which covered the period of the dictatorship only, did not cover crimes of disappearance that were, by definition, unresolved and ongoing. This led to the indictment of Pinochet and scores of other military officers. The floodgates for new and copious legal action was at least theoretically thrown open for legal recourse. But the archives, the recorded data of the crimes, were still mostly out of reach.

The Army responded to the modest thaw in the judicial branch by burning much of its archives. What remains is held tight by the army. The Carabinero archives are secret and unavailable. Even worse, in 2004, another government initiative, the Valech Commission, was convened to hear testimony from victims of torture and other abuses, as well as the families of the executed and disappeared. An astounding 40,000 Chileans testified (though the number of those who underwent torture is believed to be twice that amount). The commission was reconvened twice, in 2005 and 2010, as the demand to testify was so great.

Its findings are likely the single greatest repository of documentation related to the crimes of the dictatorship. However, thanks to the political fecklessness and cowardice of the center-left civilian governments who oversaw them, the archives were ordered locked for 50 years. If an individual can afford his or her own lawyer, it is possible to secure data from the final Valech report as it pertains to their individual case, but the public will not have access to them until 2055.

In perhaps the ultimate irony, the sealed files are kept under guarded lock and key in the Museum of Memory and Solidarity. Some pro-Boric politicians are drafting measures to open up the files to the public, but their chance of success is dim. This would require approval from Congress where Boric lacks a governing majority and where a large bloc of seats is held by parties who collaborated with or supported the dictatorship.

“The police and the military have their own private archives,” notes an activist at the Londres 38. “That material belongs in the National Archives — together with everything else from the Chilean state. But they are not letting go.”

Chile must reckon with the anniversary of the coup while strapped into the dizzying roller coaster ride that began in 2019, the year mass protests shook the country and evoked the possibility of a radical restructuring of society. These hopes were quashed by a draconian COVID-19 shutdown, then revived again in late 2021, when the leftist president Boric narrowly edged out an extreme right opponent. The administration’s first attempt to draft a new constitution ended in failure. The success and shape of the second, current effort remains uncertain.

When Boric took office, 18 months ago, the political tide had turned since the height of the 2019 protests. Public opinion was more focused on pandemic by-products like inflation and violent crime than on human rights and social justice reform. Meanwhile, the young left-wing government is backed by a younger demographic that is radically expanding Chile’s once-narrow cultural norms; the backlash is helping to reinvigorate the extreme right. Ask any Chilean about the immediate future, and regardless of their personal views, they will tell you there’s a very bumpy road ahead.

“Things are very difficult right now,” says political scientist Aguero. “But Chileans are capable of great change. Chileans are more self-assured, more confident today than in the past. But you still find many who are permanently withdrawn and quiet — remnants of generalized fear.”

Great changes in Chile have always come from the bottom up. Allende ran for president three times before he was elected in 1970, a feat made possible by near permanent organization and mobilization in the streets.

Crucially, political pressure was exerted from the belt of the shantytowns around the capital — many of them born from land seizures — that housed millions of impoverished but politicized Chileans. They were a motor force for change during the Allende government; then, despite ferocious repression, they incubated and launched the resistance to the dictatorship that followed.

Once a hot spot for organization by the Movement of the Revolutionary Left, Pinochet’s eradication of the local political leadership created holes in the social fabric that Anderson is working to repair.

Karen Anderson has been at the center of this work for decades. A longtime American-born resident of Chile, Anderson in 1982 founded EPES, an NGO that trains Chilean women to work and volunteer as public health advocates in Chile’s poorest neighborhoods. Still the organization’s director, she runs a training school that draws from health and community workers across the world.

“As an organization in deep opposition to the dictatorship, our offices were continually monitored, the neighborhoods we worked in raided,” she says. “The doctor that worked with us in Concepcion was arrested and tortured. It was a state of emergency, with 80% unemployment in the poblaciónes [the marginal settlements around Santiago].”

She tells her story as we walk toward one of these settlements, an iconic and combative neighborhood known as La Bandera. In many ways, La Bandera looks much like it did last time I saw it, 50 years ago. The children are no longer barefoot, there are more cars, but it is still a poor community. Once a hot spot for organization by the Movement of the Revolutionary Left, Pinochet’s eradication of the local political leadership created holes in the social fabric that Anderson is working to repair.

She introduces me to half-dozen very spirited middle-aged women who are organizing a community vegetable garden to improve local diets. They believe that every tomato they plant is another move toward a more democratic and just society. In Chile, these small groups have always been the building blocks of much larger social change, pressuring the political parties. They are the ones bearing the brunt of unaccountable police, poor schools, state indifference and the scorn of the country’s elite in the Barrio Alto.

Anderson believes that communities like La Bandera, having survived Pinochet’s dictatorship, will overcome the issues created by his legacy.

“Over 41 years working in low-income neighborhoods, we have seen significant changes in the level of social mobilization,” she says. “During the dictatorship, there were many community-based organizations and a massive national mobilization [of resistance]. Today, levels of social organization have changed due to drug violence, police repression and the relentless promotion of individualism and consumerism. But a grassroots movement has survived.”

She continues, “There are women’s organizations, social movements in health, environmental organizations, community gardens, cultural groups and national and international networks that contribute to concrete struggles to protect human rights and achieve dignity and justice. In short, there are reasons to remain hopeful.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.